Thomas Fazi

Apr 15, 2025

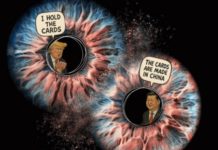

Trump’s tariff policy represents a desperate bid to preserve US economic, military and geopolitical dominance at any cost — using economic coercion against nearly every country on the planet

Over the past two weeks, Trump has taken a wrecking ball to the global economy by announcing sweeping tariffs on dozens of countries. This abrupt move sent stock markets in the US and abroad into a tailspin, forcing the administration to quickly backpedal. In a hasty retreat, Trump revised the policy to impose a lower, across-the-board 10% tariff (25% for aluminium and steel), while simultaneously singling out China with a staggering 145% tariff on all imports from the country, one of the most extreme trade measures in modern history — though some categories were subsequently exempted.

This aggressive trade policy is underpinned by two main objectives: one official and one unofficial. The official goal is to reindustrialise the US economy by reviving domestic manufacturing and reducing the trade deficit — a goal that is, in itself, legitimate. The unofficial goal, however, is far more troubling: to economically wound China in an attempt to slow or halt its rise as a global power. This fits into a broader, longstanding pattern of US efforts to preserve its global dominance — economically, militarily, and geopolitically — at virtually any cost.

What’s even more alarming is that both objectives are often framed as essential steps in preparing for a future war with China — a scenario that, however outlandish it may seem, is increasingly viewed by elements of the US establishment as not only inevitable, but perhaps even desirable.

Yet on both fronts, Trump’s tariff gamble is likely to fail. For starters, it rests on a fundamentally flawed diagnosis of America’s economic decline. The hollowing out of US industry wasn’t caused by China — but by American elites themselves. Starting in the 1980s, they embraced hyper-financialisation, prioritising short-term gains from financial markets over long-term investments in productivity and employment. They were the ones who offshored manufacturing to low-wage countries — China chief among them — enabling US corporations to reap enormous profits while decimating domestic industry and working-class communities. And it was these same elites who aggressively championed the global free trade regime that made this massive offshoring possible.

This wasn’t just an economic project, but a political one as well: it wasn’t just about giving more power to corporations, but also taking power away from the people, by surrendering national prerogatives to international and supranational institutions and super-state bureaucracies, such as the WTO and the European Union. These institutions completely untethered capital from national democracy.

Meanwhile, US elites exploited the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency, which effectively bestowed upon the United States the “exorbitant privilege” of not having to pay for its imports, unlike everyone else, because it could simply help itself to the foreign goods and services it needed by paying foreigners with its own currency, “printed” at no cost.

While this system did, to some extent, raise living standards in the US — or more accurately, cushion the blow of deindustrialisation and wage stagnation by providing American consumers access to cheap imports — it overwhelmingly benefited America’s imperial elites: Wall Street, multinational corporations and, above all, the national security establishment. Not only did the dollar’s reserve currency status turbocharge Wall Street’s rise by turning the US into the global sink for surplus capital; it’s also what allowed the US to sustain a regime of perpetual war and to exercise financial dominance over much of the world, weaponising that power for its own economic and geopolitical goals.

However, for the US, supporting the world’s primary reserve currency also entailed running permanent trade deficits in order to satisfy the world’s demand for US dollars, thus further eroding US industrial and manufacturing capacity. This is why the manufacturing share of US employment has been falling steadily for the past fifty years — long before China’s industrial rise even began. But this was a conscious decision by the American ruling class, who chose imperial dominance over economic competitiveness.

The cost of that choice wasn’t borne solely by the hundreds of millions worldwide subjected to US economic and military aggression — it was also paid by American workers, farmers, producers and small businesses, left behind in the wake of a system designed to serve elite interests. This was a global class war, orchestrated by the US imperial elite, targeting working people everywhere — both beyond America’s borders and within them.

However, this system of global imperial rent eventually broke down, for domestic as well as geopolitical reasons. Domestically, US elites did little or nothing to provide millions of blue-collar workers who lost their jobs the means of getting new ones that paid at least as well, resulting in many workers becoming permanently unemployed or being forced into low-paid, precarious jobs in the service sector, causing their wages to stagnate or fall. This fuelled social insecurity and inequality, disrupted communities, eroded social cohesion — and eventually triggered a “populist” backlash against globalisation that crystallised around Donald Trump.

Meanwhile, on a geopolitical level, something happened that US elites hadn’t predicted: China went off script. For the first time ever, a non-Western country used the US-led globalisation regime to climb its way up the global value chain. This wasn’t supposed to happen: from a US and broader Western perspective, the underlying goal of globalisation was precisely to keep developing countries locked at the bottom of the global value chain — ensuring a continuous transfer of wealth and resources from the Global South to the Global North. It was effectively a neocolonial endeavour. As JD Vance recently put it: “The idea of globalisation was that rich countries would move further up the value chain, while the poor countries made the simpler things”.

China, however, had other plans: unlike other developing countries, it retained control over its development path — institutionally, ideologically and economically. It rejected Western-dictated neoliberal reforms, the so-called Washington Consensus, in favour of a state-capitalist (or market-socialist) model where the state retained control over key industries, the banking sector, infrastructure and strategic planning. This enabled China to rapidly ascend the global value chain, emerging as a serious competitor to Western firms across multiple sectors.

But the consequences extended far beyond economics. Given China’s sheer scale and population, its successful escape from neocolonial subordination fundamentally disrupted centuries of Western hegemony, as China became a global power capable of challenging US dominance — not just economically, but in technology, geopolitics, defence and global governance.

It’s important to emphasise, however, that this process was not driven by hostility toward the US or the West — or by a desire to replace the former as the world hegemon — but by China’s own national development priorities. At its core, it was an effort to modernise the country and improve living standards — and it succeeded on an unprecedented scale, lifting nearly a billion people out of poverty in just a few decades. This stands as the most remarkable poverty reduction achievement in human history.

The geopolitical disruption was largely a by-product of this extraordinary developmental effort — an inevitable outcome of China’s return to the central economic position it historically held on the global stage for more than a thousand years prior to its subjugation by foreign powers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. China’s rise is not inherently a threat to people’s livelihoods around the world — including in the West. On the contrary, it has had a profoundly positive impact on global economic development, particularly in the Global South.

It has fuelled massive demand for natural resources and consumer goods, spurred investment in infrastructure and manufacturing zones across continents, created alternative sources of development financing and new global financial institutions, and integrated developing economies more deeply into regional and global supply chains. Overall, it has been a huge engine of global growth. Perhaps most crucially, China’s rise has empowered developing nations by offering them more diplomatic and economic options; in the new multipolar world, countries are no longer forced to choose between “aligning with the West or being isolated”, but are much freer to pursue their own development agendas — on their own terms.

The impact on Western societies has, of course, been more multifaceted. While it’s true that the so-called “China shock” contributed to the hollowing out of manufacturing and widespread job losses — particularly in the United States — this wasn’t the result of China “ripping off” America, as Trump and others claim. On the contrary, the outsourcing of production to China (and other low-cost countries) was a deliberate strategy, actively pursued by the US political and corporate elites, who reaped enormous profits from the process — even as working-class communities at home bore the costs.

Indeed, US elites likely would have continued embracing globalisation had China remained content with the subordinate role assigned to it in the global division of labour — that of manufacturing goods for Western multinationals. It was only when China refused to play by the rules and began to chart its own path of autocentric development, therefore destabilising the US-led hegemonic order — an order from which those elites have long profited, in no small part by relying on Chinese workers themselves — that they began casting it as a “systemic rival” from which the US needed to “decouple”. This concern had nothing to do with a newfound sympathy for the plight of American workers.

The global supply chain disruptions triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic, coupled with the geopolitical fracturing accelerated by the war in Ukraine, have only deepened tensions between the US and China — laying the groundwork for the full-blown trade war now being waged by Trump. As noted already, reindustrialising the US and scaling back hyper-globalisation are meaningful and legitimate goals — both from the standpoint of American workers and national security. This isn’t because China is inherently an enemy, but because reducing excessive reliance on far-flung supply chains for critical goods is simply a matter of common sense.

However, for this strategy to succeed, it must be grounded in an accurate diagnosis of the problem — and an effective remedy. Trump’s policy, however, fails on both counts. His administration’s entire tariff narrative is based on the idea that the hollowing out of US manufacturing and related import dependencies are the result of other countries — chief among them China — “ripping off” and “free-riding” on America. As Trump put it:

For decades, our country has been looted, pillaged, raped and plundered by nations near and far, both friend and foe alike. American steelworkers, auto workers, farmers and skilled craftsmen, we have a lot of them here with us today. They really suffered gravely. They watched in anguish as foreign leaders have stolen our jobs, foreign cheaters have ransacked our factories and foreign scavengers have torn apart our once beautiful American dream.

This is gaslighting on a grand scale: it’s the world’s largest economic and military power playing the victim and blaming others for the consequences of its own elite-driven policies and the class war waged by the US ruling classes against their fellow citizens.

Rebalancing the US economy requires confronting the true structural roots of its decline: hyper-financialisation, chronic underinvestment in domestic industry, imperial overstretch and — perhaps most crucially — the global reserve currency status of the US dollar.

Reviving American manufacturing is not merely a matter of tariffs or reshoring policies; it demands relinquishing the dollar’s supremacy and, by extension, the imperial foundations of US power. In essence, it calls for the United States to embrace multipolarity and evolve into a more “normal” nation — a regional power among other regional powers, rather than a guardian of the global economic order — by engaging with other countries, first and foremost China, to manage the transition to a post-dollar-dominated global trading and financial system. Both globally and within the US, this would benefit virtually everyone — except the imperial elites who got the country into this mess in the first place.

Regrettably, this is not the path being pursued by the Trump administration. On the contrary, Trump has repeatedly taken a hostile stance toward BRICS, openly expressing his opposition to the emergence of an alternative reserve currency or a reserve basket. He has made it clear that such talk must end, and that he will do whatever it takes to ensure the US dollar remains the world’s dominant reserve currency, reflecting his ambition for the US to reclaim its position at the top of the global hierarchy. However, this goal is fundamentally incompatible with Trump’s stated aim of reducing the trade deficit.

Yet his administration seems to think the US can have its cake and eat it too — retain the dominant status of the dollar while simultaneously forcing countries to subsidise the reindustrialisation of the US economy. Indeed, in a remarkable speech, Steve Miran, chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, argued that other countries should compensate the United States for the “burden” it bears in supplying the world with a “global public good” — namely, the US dollar’s status as the global reserve currency and the “security umbrella” that it underpins. According to Miran, such compensation could take the form of accepting US tariffs without retaliation, increasing imports of American goods or even — as he put it — “simply writ[ing] checks to Treasury that help us finance global public goods”.

In other words, rather than relinquish the extractive privileges of empire to focus on rebuilding an industrial base, the Trump administration is, in effect, demanding that the rest of the world pay an imperial tribute for the supposed “benefits” of US economic and military protection — compensating America for the “burdens” of its global dominance — while simultaneously insisting that other countries align with the US in its trade war against China. As Scott Bessent, Trump’s Treasury secretary, put it, countries that don’t comply with US demands will be designated as “foes” — implying that they could face not only economic retaliation, but also non-economic forms of pressure, including military coercion.

Clearly, Trump’s tariff policy is about far more than reducing the US trade deficit; it represents a desperate bid to preserve American economic, military and geopolitical dominance at any cost — using economic coercion against nearly every country on the planet and China in particular. It is, in essence, the continuation (or rather the anticipation) of war by other means.

However, it’s a war the US is destined to lose, for several reasons. For starters, the US’s ability to leverage tariffs to exert economic pressure on other countries is much more limited than it used to be: despite its historical role as the world’s “consumer of last resort”, the US today accounts for less than 15 percent of global imports — roughly the same percentage as China, which has emerged as the largest trading partner of over 150 nations. Simply put, the US market is not as important as it once was.

In this context, forcing the world to choose between the US and China is a non-starter. Indeed, as Prof. Warwick Powell has argued, the most likely consequence of US tariffs — and China’s countermeasures — is that Chinese consumers and businesses, confronted with the rising cost of American goods, will increasingly turn to alternative suppliers from other parts of the world. This shift will be facilitated by China’s relatively lower tariff barriers and could provide a crucial cushion for countries adversely affected by Trump’s trade war — helping to absorb some of the economic fallout from Trump’s tariffs.

Meanwhile, it is highly unlikely that most countries — particularly in the Global South, where many nations are already members of, or aspiring entrants to, BRICS — will willingly undermine their own economic interests by adopting Washington’s tariff agenda against China. Few are prepared to reduce their imports from (or compromise their exports to) one of the world’s largest trading partners simply to accommodate Trump’s geopolitical ambitions. In fact, as China positions itself as a defender of the multilateral trading system in the face of Trump’s attempts to dismantle it, we are likely to see countries across the Global South strengthen their bilateral and multilateral trade ties — not only with one another, but with China itself.

Rather than isolating China, these tariffs will likely deepen its trade relations with the global majority, further energising BRICS, accelerating the ongoing decoupling from the dollar-dominated trade and financial architecture, and reinforcing the shift towards a multipolar world order. Even the European Union, which has historically aligned with the United States on China policy, is now seeking closer economic engagement with Beijing — especially as the US emerges as an increasingly erratic, unreliable and outright threatening partner. It is the US that risks being (further) isolated from the rest of the world, including potentially from some of its European satellites — not China. In short, in geopolitical terms, the tariffs will end up producing the exact opposite of what Trump intended — much like the Western sanctions on Russia, which only pushed Moscow into deeper cooperation with the non-Western world.

Will the tariffs — and Trump’s full-scale trade war against China — deliver better outcomes for the US in strictly economic terms? This too seems unlikely. Much of what is labeled as “Chinese exports” to the US are, in fact, American products manufactured in China — meaning the lion’s share of the value is captured by US corporations. As a result, it is these very companies that stand to be most harmed by the tariffs.

This is why Trump, likely under strong pressure from US high-tech companies, was quick to announce tariff exemptions for smartphones, computers and other electronic devices imported from China — though he also suggested the exemptions could be short-lived. This underscores a key reality: if Trump is serious about bringing manufacturing back to the US, one of his biggest challenges will be compelling American corporations to take a financial hit in service of broader economic goals. Meanwhile, China’s retaliatory tariffs of 125% on all US goods will inevitably undermine US exports to the country, further hampering the output and profit margins of US corporations. Thus, in the short term, the US is likely to pay a significantly higher economic price for the trade war with China than China itself.

The longer-term logistical and economic challenges involved in rejuvenating and reshoring US manufacturing are even greater. Modern manufacturing generally requires machinery and intermediate inputs that are sourced from a wide array of countries. According to the US National Association of Manufacturers, a staggering 56 percent of goods imported to the US are actually manufacturing inputs — many of which coming from China itself. To establish a viable manufacturing base, the US will either need to import these inputs — in which case tariffs are utterly self-defeating — or invest heavily in building domestic supply chains from scratch. This is not an impossible feat, but it is one that will be time-consuming, technically complex and extremely costly.

Thinking that tariffs will magically spur the kind of structural changes needed to re-energise US manufacturing is delusional. Achieving this will require nothing less than a radical overhaul of the US economic model — one that, ironically, involves borrowing a page or two from China’s own book. As noted already, and contrary to Trump’s narrative, China didn’t rise to become the world’s leading producer in key sectors by engaging in so-called “unfair trade practices” like subsidies — practices that, in fact, are widespread across all advanced economies, including the United States.

Rather, China’s success is rooted in the distinctive features of its economic model: a long-term, state-directed approach to industrial policy and strategic planning, including public control over the financial system and key industries. This model enables the Chinese state to mobilise resources, coordinate investments and guide technological development in a way that private capital in the US — driven primarily by short-term profit motives unanchored from any long-term national strategy — is unable to match.

The lesson is clear: if the US wants to rebuild its manufacturing base, it needs to break once and for all with neoliberalism and the tyranny of private capital instead of engaging in a self-defeating war against China. As it stands, however, there is little indication that such a shift is politically viable under Trump — or within the US more broadly. As Michael Hudson recently wrote:

[Trump’s] cover story, and perhaps even his belief, is that tariffs by themselves can revive American industry. But he has no plans to deal with the problems that caused America’s deindustrialization in the first place. There is no recognition of what made the original US industrial program and that of most other nations so successful. That program was based on public infrastructure, rising private industrial investment and wages protected by tariffs, and strong government regulation. Trump’s slash and burn policy is the reverse — to downsize government, weaken public regulation and sell off public infrastructure to help pay for his income tax cuts on his Donor Class.

This shouldn’t surprise us: as a manifestation of the broader problem — the oligarchic grip on the US economy — Trump cannot serve as its remedy.

READ ALSO: From the War Against Russia to the War Against China. American vs. Russian ‘Nationalism’

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.