by

In 2018 the Trades Union Congress (TUC) celebrated its 150th birthday. Yesterday the government delivered a somewhat belated birthday present to the union movement in the form of new statistics showing that membership levels have risen significantly for the first time in almost two decades. Happy birthday TUC!

In this short blog post, we provide a bit more detail on this headline finding and drill down into other important (and frankly less cheerful gifts) to be found within the latest data. Here are five key points to take away from the statistics.

-

Membership levels have risen by the largest amount since 2000

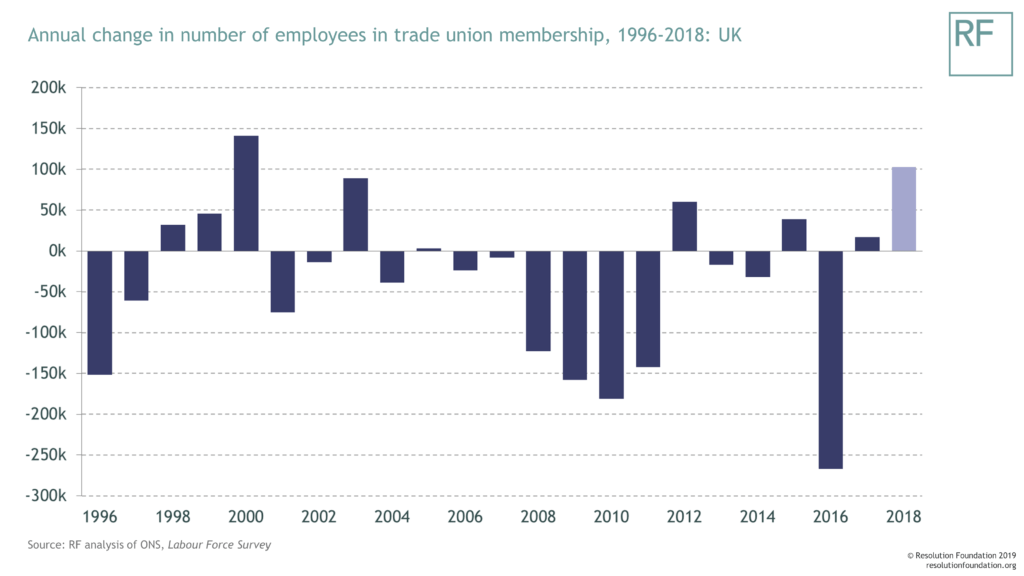

We’ve had some big falls in trade union membership levels recently, but 2018 was an exception. The latest figures show that the number of employees in union membership increased by over 100,000 last year. This is more than in any year since the turn of the century, and the second highest single year increase in the number of people in a trade union in the 23 years for which these statistics have been published.

In total there are now 6.7 million people who are members of trade unions in the UK. There aren’t many organisations that can claim a membership of this size. However, the number of people in union membership is considerably lower than when unions were at their peak (there were 13 million members in 1979), and it’s over 200,000 lower than in 2010 – despite the number of people in work in the UK increasing by almost three million over that period. This dynamic of falling or flat membership amid a fast growing workforce is why it’s important to track trade union density too.

-

Trade union density has risen, but only by a very small amount

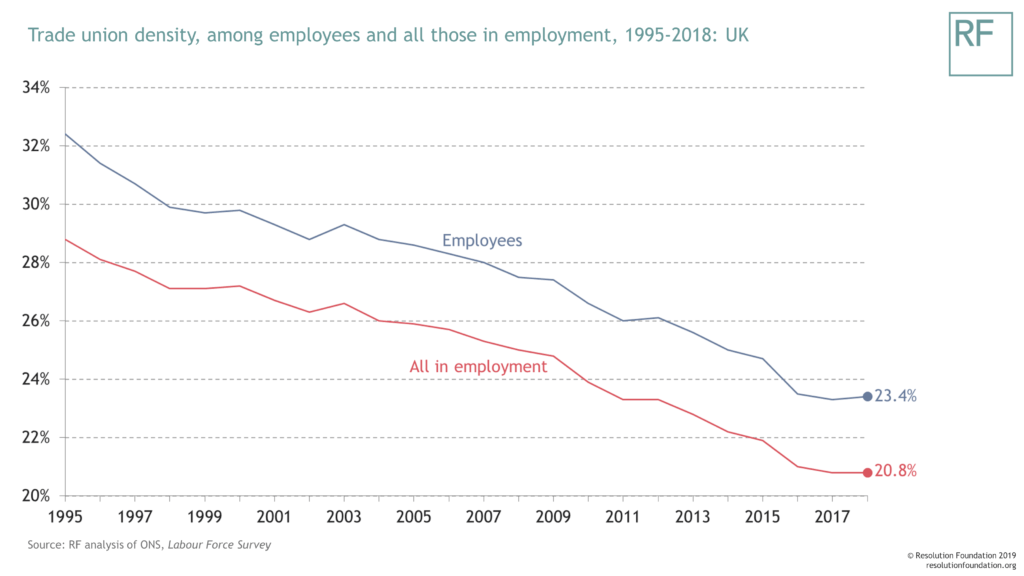

Trade union density measures the proportion of employees (or all those in employment) that are union members. It provides a better estimate of the overall strength of the labour movement in the UK than the headline number of members.

On this metric, unions have also seen an improvement in their position over the course of 2018. Trade union density ticking up by 0.1 percentage points among employees, and remained unchanged among all those in employment. As the chart below shows, 23.4 per cent of employees (or 20.8 per cent of all those in employment) are union members.

The improvement in union density over 2018 is very small and it would be a mistake to claim that falling union density is now a thing of the past in the UK. That said, this could be the first sign of things bottoming out. There’s been a growing sense in recent years from those inside the union movement that recruitment – particularly of younger workers – was something that needed to be prioritised more than ever.

-

This year’s increase was driven by increasing membership rates in the public sector

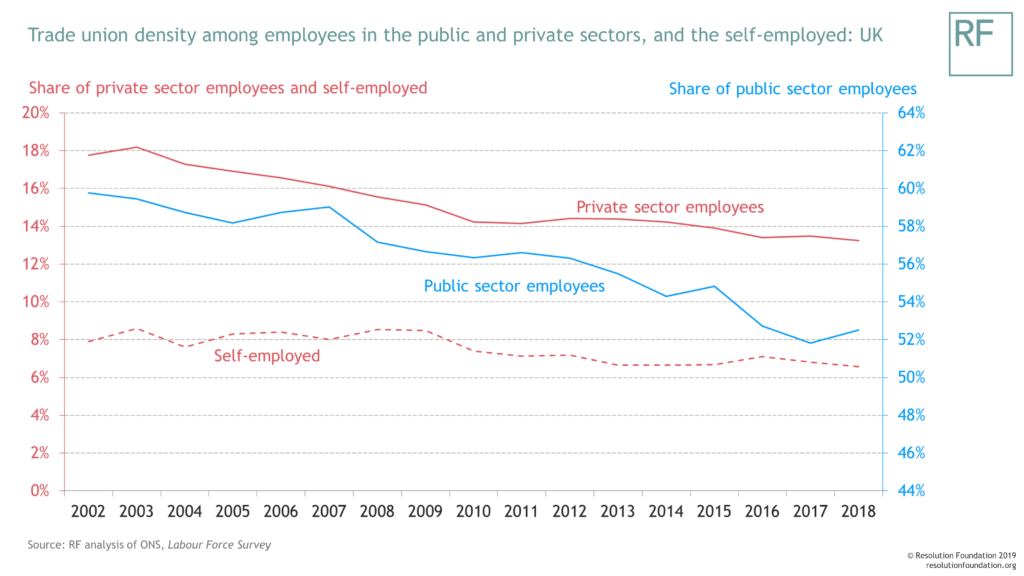

Trade union members are heavily concentrated in the public sector. More than half of public sector employees are trade union members, compared to just 13 per cent of employees in the private sector and 7 per cent of the self-employed.

This year, trade union density has continued to fall among private sector employees – from 13.5 per cent to 13.2 per cent – continuing the story of a long, slow, decline in this part of the jobs market. Membership rates among the self-employed are also down slightly, from 6.8 per cent to 6.6 per cent. The trends in these figures back to the early 2000s are shown in the chart below.

The chart shows too how membership rates have increased over the past year in the public sector. It’s this part of the jobs market that has driven the overall positive story discussed above. In particular, membership in public administration grew by 100,000 in 2018, the same amount as the overall increase in membership over the past year.

We can’t explain what’s happened among those working in public administration at this stage, though of course part of the story is that this corner of the jobs market has grown substantially as the civil service has expanded in the wake of the 2016 EU referendum. In general, it’s important not to get too hung up on the specific changes that take place within different industries from year to year – these numbers can fluctuate substantially and the long-run trend is more worthy of our attention.

-

Trade union membership is still predominantly composed of well-paid, public sector workers

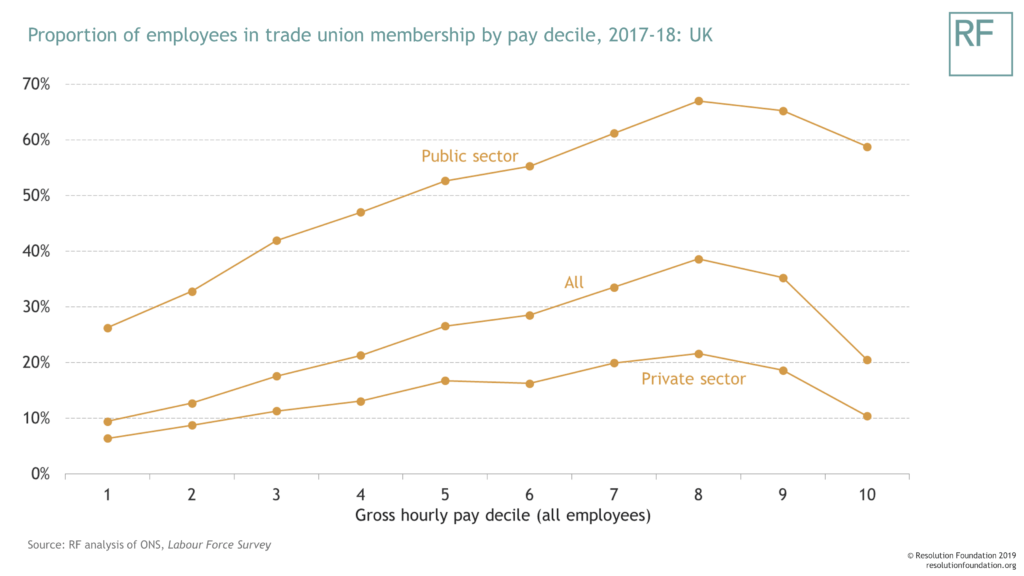

The difference in the rate of membership between the public and private sectors is large, but the inequality in workplace representation is larger still when membership at different points in the earnings distribution are considered.

You are significantly more likely to be a trade union member in higher-paid public sector roles (where membership is 67 per cent), than in the lowest paid private sector roles (where membership is 6.4 per cent). Ten times more likely in fact. Unions, sadly, are still weakest where they are needed most.

-

Demographics is (a worrying) destiny for trade unions

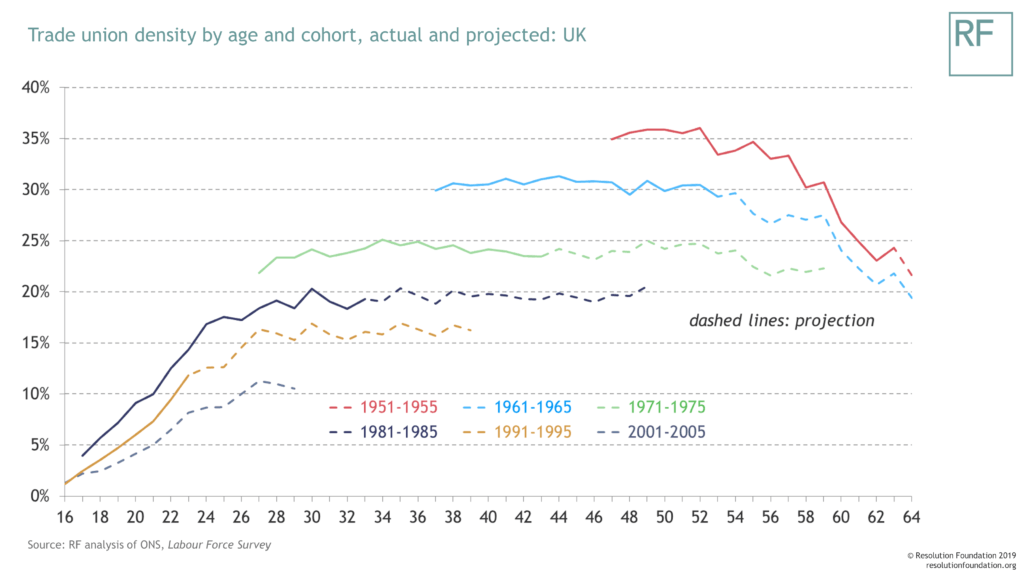

The big picture story hiding behind the long-run fall in membership is that each new cohort of workers starting out in the labour market are less likely to be union members than their predecessors. This presents a problem for membership rates in the long run because older cohorts (e.g. those born in the 1950s) who started out in the labour market when union membership was at its peak (in the 1970s) are now at or nearing retirement.

As these cohorts, for example the 1951-1955 cohort shown in red on the chart below, leave the labour market and new cohorts (e.g. the 1991-1995 cohort shown by the gold line below) enter work, the mechanics of demographic change mean that the rate of union membership will continue to fall.

To get a sense of the scale of this challenge, we’ve projected every cohort’s union membership rate out to 2030. We do this by making the simple assumption that changes in membership rates track the path of membership rates for the immediately preceding cohort. This work leaves us with a concerning finding: if current trends continue then trade union membership could fall to as little as 16 per cent by 2030.

This matters. Trade unions are the primary way in which workers have historically – and still do – exercise their power in the workplace. Winning rights, improving conditions and getting a better deal in terms of pay and hours are all things that have been won for workers with the help, and leadership, of trade unions. The prospects for the exercise of worker power continuing in the years ahead are much diminished if membership rates fall in line with our projections.

Whether it be a revival in trade unionism or new institutions offering new ways of enhancing the position of workers – it seems increasingly likely that the UK needs a re-set of worker power in the years ahead, this is something we at the Resolution Foundation will be looking in more detail at in the months to come.