August 20, 2017

Fifty years ago, I could have tried to stop the Vietnam War, but lacked the courage. On Aug. 20, 1967, we at CIA received a cable from Saigon containing documentary proof that the U.S. commander, Gen. William Westmoreland, and his deputy, Gen. Creighton Abrams, were lying about their “success” in fighting the Vietnamese Communists. I live with regret that I did not blow the whistle on that when I could have.

(I wrote about this two years ago: “The Lasting Pain from Vietnam Silence,” republished below.)

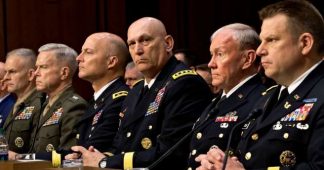

Why raise this now? Because President Donald Trump has surrounded himself with starry-eyed generals (or generals with their eyes focused on their careers). And he seems to have little inkling that they got their multiple stars under a system where the Army motto “Duty, Honor, Country” can now be considered as “quaint” and “obsolete” as the Bush-Cheney administration deemed the Geneva Conventions.

All too often, the number of ribbons and merit badges festooned on the breasts of U.S. generals these days (think of the be-medaled Gen. David Petraeus, for example) is in direct proportion to the lies they have told in saluting smartly and abetting the unrealistic expectations of their political masters (and thus winning yet another star).

In my apologia that follows, the concentration is on the crimes of Westmoreland and the generations of careerist generals who aped him. There is not enough space to describe (or even list) those sycophantic officers here.

There are, sadly, far fewer senior officers who were exceptions, who put the true interests of the country ahead of their own careers. The list of general officers with integrity – the extreme exceptions to the rule – is even shorter. Only three spring immediately to mind: two generals and one admiral, all three of them cashiered for doing their job with honesty. What they experienced was instructive and remains so to this day.

1-On February 25, 2003, three weeks before the attack on Iraq, Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki warned the Senate Armed Services Committee that post-war Iraq would require “something on the order of several hundred thousand soldiers.” He was immediately ridiculed by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and his deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, for having exaggerated the requirement. Shinseki retired a few months later.

2-Army General David McKiernan was cut from the same cloth. When President Barack Obama took office, McKiernan was running the war in Afghanistan. Even before Obama’s election, he had expressed himself openly and strongly against applying the benighted Iraq-style “surge” of forces to Afghanistan, emphasizing that Afghanistan is “a far more complex environment than I ever found in Iraq,” where he had led U.S. ground forces.

“The word I don’t use for Afghanistan is ‘surge,’” McKiernan told a news conference on Oct. 1, 2008. He warned that a large, sustained military buildup would be necessary to achieve any meaningful success. Worse still for the Washington Establishment, McKiernan added a stunning “no-no” – he said to achieve anything approaching a satisfactory outcome would take a decade, perhaps 14 years. Imagine!

For his political bosses, that cautionary realism was too much. On May 11, 2009, the Defense Secretary whom Obama’s predecessor bequeathed to him, Robert Gates, sacked McKiernan, who had been in command less than a year. Gates replaced him with the swashbuckling Gen. Stanley McChrystal, a protégé of Gen. (and later CIA Director) David Petraeus.

Now, more than eight years later – with the American death toll almost quadrupled since the start of the Obama administration (now exceeding 2,400), with a vastly greater death toll among Afghan civilians and with the U.S. military position even more precarious – President Trump is receiving advice to dispatch more U.S. troops.

3-Admiral William J. (“Fox”) Fallon, one of the last Vietnam War veterans on active duty late into George W. Bush’s administration, took over as chief of the Central Command on March 16, 2007. Fallon had already come under heavy criticism from the neoconservative American Enterprise Institute for not being hawkish enough.

Fallon had also been confronting Vice President Dick Cheney’s desire to commit U.S. forces to another Mideast war, with Iran. As Fallon was preparing to take responsibility for U.S. forces in the region, he declared that a war with Iran “isn’t going to happen on my watch,” according to retired Army Col. Patrick Lang who told the Washington Post.

Fallon’s lack of patience with yes-men turned out to be yet another bureaucratic black mark against him. Several sources have reported that Fallon was sickened by David Petraeus’s earlier, unctuous pandering to ingratiate himself with Fallon, his superior (for all-too-short a time). Fallon is said to have been so turned off by all the accolades in a flowery introduction given him by Petraeus that he called him to his face “an ass-kissing little chicken-shit,” adding, “I hate people like that.”

Fallon lasted not quite a full year. On March 11, 2008, Gates announced the resignation of Fallon as CENTCOM Commander, but Fallon’s resistance to a war on Iran bought enough time for the U.S. intelligence community to reach a consensus that Iran had stopped work on a nuclear bomb years earlier, thus removing President Bush’s intended excuse for going to war.

A Troubling Message

Sadly, however, the message to aspiring military commanders from this history is that there is little personal gain in doing what’s best for the American people and the world. The promotions and the prestige normally go to the careerists who bend to the self-aggrandizing realities of Official Washington. They are the ones who typically become esteemed “wise men,” the likes of Gen. Colin Powell, who went with the political winds (from his days as a young officer in Vietnam through his tenure as Secretary of State).

Someone needs to tell President Trump what Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity told President George W. Bush in a memorandum for the President on February 5, 2003, immediately following Powell’s deceptive testimony urging the United Nations’ Security Council to support an invasion of Iraq. What we said then seems just as urgent now:

“[A]fter watching Secretary Powell today, we are convinced that you would be well served if you widened the discussion beyond … the circle of those advisers clearly bent on a war for which we see no compelling reason and from which we believe the unintended consequences are likely to be catastrophic.”

And on the chance that President Trump remains tone-deaf to such advice, let me appeal to the consciences of those within the system who are privy to the kind of consequential deceit that has become endemic to the U.S. government. It is time to blow the whistle – now.

Take it from one who lives with regret from choosing not to step forward when it might have made a difference. Take it from Pentagon Papers truth-teller Daniel Ellsberg who often expresses regret that he did not speak out sooner.

Take it from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in a passage ironically cited often by President Obama: “We are now faced with the fact that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now … there is such a thing as being too late.”

[Below is McGovern’s article from May 1, 2015]

The Lasting Pain from Vietnam Silence

Exclusive: Many reflections on America’s final days in Vietnam miss the point, pondering whether the war could have been won or lamenting the fate of U.S. collaborators left behind. The bigger questions are why did the U.S. go to war and why wasn’t the bloodletting stopped sooner, as ex-CIA analyst Ray McGovern reflects.

By Ray McGovern

Ecclesiastes says there is a time to be silent and a time to speak. The fortieth anniversary of the ugly end of the U.S. adventure in Vietnam is a time to speak and especially of the squandered opportunities that existed earlier in the war to blow the whistle and stop the killing.

While my friend Daniel Ellsberg’s leak of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 eventually helped to end the war, Ellsberg is the first to admit that he waited too long to reveal the unconscionable deceit that brought death and injury to millions.

I regret that, at first out of naiveté and then cowardice, I waited even longer until my own truth-telling no longer really mattered for the bloodshed in Vietnam. My hope is that there may be a chance this reminiscence might matter now if only as a painful example of what I could and should have done, had I the courage back then. Opportunities to blow the whistle in time now confront a new generation of intelligence analysts whether they work on Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, ISIS or Iran.

Incidentally, on Iran, there was a very positive example last decade: courageous analysts led by intrepid (and bureaucratically skilled) former Assistant Secretary of State for Intelligence Thomas Fingar showed that honesty can still prevail within the system, even when truth is highly unwelcome.

The unanimous intelligence community conclusion of a National Intelligence Estimate of 2007 that Iran had stopped working on a nuclear weapon four years earlier played a huge role in thwarting plans by President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney to attack Iran in 2008, their last year in office. Bush says so in his memoir; and, on that one point, we can believe him.

After a half-century of watching such things closely, this is the only time in my experience that the key judgment of an NIE helped prevent a catastrophic, unwinnable war. Sadly, judging from the amateurism now prevailing in Washington’s opaque policymaking circles, it seems clear that the White House pays little heed to those intelligence officers still trying to speak truth to power.

For them I have a suggestion: Don’t just wring your hands, with an “I did everything I could to get the truth out.” Chances are you have not done all you can. Ponder the stakes the lives ended too early; the bodies and minds damaged forever; the hatred engendered against the United States; and the long-term harm to U.S. national interests and think about blowing the whistle publicly to prevent unnecessary carnage and alienation.

I certainly wish I had done so about what I learned of the unconscionable betrayal by senior military and intelligence officers regarding Vietnam. More recently, I know that several of you intelligence analysts with a conscience wish you had blown the whistle on the fraud “justifying” war on Iraq. Spreading some truth around is precisely what you need to do now on Syria, Iraq, Ukraine and the “war on terror,” for example.

I thought that by describing my own experience negative as it is and the remorse I continue to live with, I might assist those of you now pondering whether to step up to the plate and blow the whistle now, before it is again too late. So below is an article that I might call “Vietnam and Me.”

My hope is to spare you the remorse of having to write, a decade or two from now, your own “Ukraine and Me” or “Syria and Me” or “Iraq and Me” or “Libya and Me” or “The War on Terror and Me.” My article, from 2010, was entitled “How Truth Can Save Lives” and it began:

If independent-minded Web sites, like WikiLeaks or, say, Consortiumnews.com, existed 43 years ago, I might have risen to the occasion and helped save the lives of some 25,000 U.S. soldiers, and a million Vietnamese, by exposing the lies contained in just one SECRET/EYES ONLY cable from Saigon.

I need to speak out now because I have been sickened watching the herculean effort by Official Washington and our Fawning Corporate Media (FCM) to divert attention from the violence and deceit in Afghanistan, reflected in thousands of U.S. Army documents, by shooting the messenger(s), WikiLeaks and Pvt. Bradley Manning.

After all the indiscriminate death and destruction from nearly nine years of war, the hypocrisy is all too transparent when WikiLeaks and suspected leaker Manning are accused of risking lives by exposing too much truth. Besides, I still have a guilty conscience for what I chose NOT to do in exposing facts about the Vietnam War that might have saved lives.

The sad-but-true story recounted below is offered in the hope that those in similar circumstances today might show more courage than I was able to muster in 1967, and take full advantage of the incredible advancements in technology since then.

Many of my Junior Officer Trainee Program colleagues at CIA came to Washington in the early Sixties inspired by President John Kennedy’s Inaugural speech in which he asked us to ask ourselves what we might do for our country. (Sounds corny nowadays, I suppose; I guess I’ll just have to ask you to take it on faith. It may not have been Camelot exactly, but the spirit and ambience were fresh, and good.)

Among those who found Kennedy’s summons compelling was Sam Adams, a young former naval officer out of Harvard College. After the Navy, Sam tried Harvard Law School, but found it boring. Instead, he decided to go to Washington, join the CIA as an officer trainee, and do something more adventurous. He got more than his share of adventure.

Sam was one of the brightest and most dedicated among us. Quite early in his career, he acquired a very lively and important account, that of assessing Vietnamese Communist strength early in the war. He took to the task with uncommon resourcefulness and quickly proved himself the consummate analyst.

Relying largely on captured documents, buttressed by reporting from all manner of other sources, Adams concluded in 1967 that there were twice as many Communists (about 600,000) under arms in South Vietnam as the U.S. military there would admit.

Dissembling in Saigon

Visiting Saigon during 1967, Adams learned from Army analysts that their commanding general, William Westmoreland, had placed an artificial cap on the official Army count rather than risk questions regarding “progress” in the war (sound familiar?).

It was a clash of cultures; with Army intelligence analysts saluting generals following politically dictated orders, and Sam Adams aghast at the dishonesty, consequential dishonesty. From time to time I would have lunch with Sam and learn of the formidable opposition he encountered in trying to get out the truth.

Commiserating with Sam over lunch one day in late August 1967, I asked what could possibly be Gen. Westmoreland’s incentive to make the enemy strength appear to be half what it actually was. Sam gave me the answer he had from the horse’s mouth in Saigon.

Adams told me that in a cable dated Aug. 20, 1967, Westmoreland’s deputy, Gen. Creighton Abrams, set forth the rationale for the deception. Abrams wrote that the new, higher numbers (reflecting Sam’s count, which was supported by all intelligence agencies except Army intelligence, which reflected the “command position”) “were in sharp contrast to the current overall strength figure of about 299,000 given to the press.”

Abrams emphasized, “We have been projecting an image of success over recent months” and cautioned that if the higher figures became public, “all available caveats and explanations will not prevent the press from drawing an erroneous and gloomy conclusion.”

No further proof was needed that the most senior U.S. Army commanders were lying, so that they could continue to feign “progress” in the war. Equally unfortunate, the crassness and callousness of Abrams’s cable notwithstanding, it had become increasingly clear that rather than stand up for Sam, his superiors would probably acquiesce in the Army’s bogus figures. Sadly, that’s what they did.

CIA Director Richard Helms, who saw his primary duty quite narrowly as “protecting” the agency, set the tone. He told subordinates that he could not discharge that duty if he let the agency get involved in a heated argument with the U.S. Army on such a key issue in wartime.

This cut across the grain of what we had been led to believe was the prime duty of CIA analysts, to speak truth to power without fear or favor. And our experience thus far had shown both of us that this ethos amounted to much more than just slogans. We had, so far, been able to “tell it like it is.”

After lunch with Sam, for the first time ever, I had no appetite for dessert. Sam and I had not come to Washington to “protect the agency.” And, having served in Vietnam, Sam knew first hand that thousands upon thousands were being killed in a feckless war.

What to Do?

I have an all-too-distinct memory of a long silence over coffee, as each of us ruminated on what might be done. I recall thinking to myself; someone should take the Abrams cable down to the New York Times (at the time an independent-minded newspaper).

Clearly, the only reason for the cable’s SECRET/EYES ONLY classification was to hide deliberate deception of our most senior generals regarding “progress” in the war and deprive the American people of the chance to know the truth.

Going to the press was, of course, antithetical to the culture of secrecy in which we had been trained. Besides, you would likely be caught at your next polygraph examination. Better not to stick your neck out.

I pondered all this in the days after that lunch with Adams. And I succeeded in coming up with a slew of reasons why I ought to keep silent: a mortgage; a plum overseas assignment for which I was in the final stages of language training; and, not least, the analytic work, important, exciting work on which Sam and I thrived.

Better to keep quiet for now, grow in gravitas, and live on to slay other dragons. Right?

One can, I suppose, always find excuses for not sticking one’s neck out. The neck, after all, is a convenient connection between head and torso, albeit the “neck” that was the focus of my concern was a figurative one, suggesting possible loss of career, money and status not the literal “necks” of both Americans and Vietnamese that were on the line daily in the war.

But if there is nothing for which you would risk your career “neck” like, say, saving the lives of soldiers and civilians in a war zone your “neck” has become your idol, and your career is not worthy of that. I now regret giving such worship to my own neck. Not only did I fail the neck test. I had not thought things through very rigorously from a moral point of view.

Promises to Keep?

As a condition of employment, I had signed a promise not to divulge classified information so as not to endanger sources, methods or national security. Promises are important, and one should not lightly violate them. Plus, there are legitimate reasons for protecting some secrets. But were any of those legitimate concerns the real reasons why Abrams’s cable was stamped SECRET/EYES ONLY? I think not.

It is not good to operate in a moral vacuum, oblivious to the reality that there exists a hierarchy of values and that circumstances often determine the morality of a course of action. How does a written promise to keep secret everything with a classified stamp on it square with one’s moral responsibility to stop a war based on lies? Does stopping a misbegotten war not supersede a secrecy promise?

Ethicists use the words “supervening value” for this; the concept makes sense to me. And is there yet another value? As an Army officer, I had taken a solemn oath to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States from all enemies, foreign and domestic.

How did the lying by the Army command in Saigon fit in with that? Were/are generals exempt? Should we not call them out when we learn of deliberate deception that subverts the democratic process? Can the American people make good decisions if they are lied to?

Would I have helped stop unnecessary killing by giving the New York Times the not-really-secret, SECRET/EYES ONLY cable from Gen. Abrams? We’ll never know, will we? And I live with that. I could not take the easy way out, saying Let Sam Do It. Because I knew he wouldn’t.

Sam chose to go through the established grievance channels and got the royal run-around, even after the Communist countrywide offensive at Tet in January-February 1968 proved beyond any doubt that his count of Communist forces was correct.

When the Tet offensive began, as a way of keeping his sanity, Adams drafted a caustic cable to Saigon saying, “It is something of an anomaly to be taking so much punishment from Communist soldiers whose existence is not officially acknowledged.” But he did not think the situation at all funny.

Dan Ellsberg Steps In

Sam kept playing by the rules, but it happened that unbeknown to Sam Dan Ellsberg gave Sam’s figures on enemy strength to the New York Times, which published them on March 19, 1968. Dan had learned that President Lyndon Johnson was about to bow to Pentagon pressure to widen the war into Cambodia, Laos and up to the Chinese border perhaps even beyond.

Later, it became clear that his timely leak together with another unauthorized disclosure to the Times that the Pentagon had requested 206,000 more troops prevented a wider war. On March 25, Johnson complained to a small gathering, “The leaks to the New York Times hurt us. We have no support for the war. I would have given Westy the 206,000 men.”

Ellsberg also copied the Pentagon Papers the 7,000-page top-secret history of U.S. decision-making on Vietnam from 1945 to 1967 and, in 1971, he gave copies to the New York Times, Washington Post and other news organizations.

In the years since, Ellsberg has had difficulty shaking off the thought that, had he released the Pentagon Papers sooner, the war might have ended years earlier with untold lives saved. Ellsberg has put it this way: “Like so many others, I put personal loyalty to the president above all else above loyalty to the Constitution and above obligation to the law, to truth, to Americans, and to humankind. I was wrong.”

And so was I wrong in not asking Sam for a copy of that cable from Gen. Abrams. Sam, too, eventually had strong regrets. Sam had continued to pursue the matter within CIA, until he learned that Dan Ellsberg was on trial in 1973 for releasing the Pentagon Papers and was being accused of endangering national security by revealing figures on enemy strength.

Which figures? The same old faked numbers from 1967! “Imagine,” said Adams, “hanging a man for leaking faked numbers,” as he hustled off to testify on Dan’s behalf. (The case against Ellsberg was ultimately thrown out of court because of prosecutorial abuses committed by the Nixon administration.)

After the war drew down, Adams was tormented by the thought that, had he not let himself be diddled by the system, the entire left half of the Vietnam Memorial wall would not be there. There would have been no new names to chisel into such a wall.

Sam Adams died prematurely at age 55 with nagging remorse that he had not done enough.

In a letter appearing in the (then independent-minded) New York Times on Oct. 18, 1975, John T. Moore, a CIA analyst who worked in Saigon and the Pentagon from 1965 to 1970, confirmed Adams’s story after Sam told it in detail in the May 1975 issue of Harper’s magazine.

Moore wrote: “My only regret is that I did not have Sam’s courage. The record is clear. It speaks of misfeasance, nonfeasance and malfeasance, of outright dishonesty and professional cowardice.

“It reflects an intelligence community captured by an aging bureaucracy, which too often placed institutional self-interest or personal advancement before the national interest. It is a page of shame in the history of American intelligence.”

Tanks But No Thanks, Abrams

What about Gen. Creighton Abrams? Not every general gets the Army’s main battle tank named after him. The honor, though, came not from his service in Vietnam, but rather from his courage in the early day of his military career, leading his tanks through German lines to relieve Bastogne during World War II’s Battle of the Bulge. Gen. George Patton praised Abrams as the only tank commander he considered his equal.

As things turned out, sadly, 23 years later Abrams became a poster child for old soldiers who, as Gen. Douglas McArthur suggested, should “just fade away,” rather than hang on too long after their great military accomplishments.

In May 1967, Abrams was picked to be Westmoreland’s deputy in Vietnam and succeeded him a year later. But Abrams could not succeed in the war, no matter how effectively “an image of success” his subordinates projected for the media. The “erroneous and gloomy conclusions of the press” that Abrams had tried so hard to head off proved all too accurate.

Ironically, when reality hit home, it fell to Abrams to cut back U.S. forces in Vietnam from a peak of 543,000 in early 1969 to 49,000 in June 1972, almost five years after Abrams’s progress-defending cable from Saigon. By 1972, some 58,000 U.S. troops, not to mention two to three million Vietnamese, had been killed.

Both Westmoreland and Abrams had reasonably good reputations when they started out, but not so much when they finished.

And Petraeus?

Comparisons can be invidious, but Gen. David Petraeus is another Army commander who has wowed Congress with his ribbons, medals and merit badges. A pity he was not born early enough to have served in Vietnam where he might have learned some real-life hard lessons about the limitations of counterinsurgency theories.

Moreover, it appears that no one took the trouble to tell him that in the early Sixties we young infantry officers already had plenty of counterinsurgency manuals to study at Fort Bragg and Fort Benning. There are many things one cannot learn from reading or writing manuals, as many of my Army colleagues learned too late in the jungles and mountains of South Vietnam.

Unless one is to believe, contrary to all indications, that Petraeus is not all that bright, one has to assume he knows that the Afghanistan expedition is a folly beyond repair. So far, though, he has chosen the approach taken by Gen. Abrams in his August 1967 cable from Saigon. That is precisely why the ground-truth of the documents released by WikiLeaks is so important.

Whistleblowers Galore

And it’s not just the WikiLeaks documents that have caused consternation inside the U.S. government. Investigators reportedly are rigorously pursuing the source that provided the New York Times with the texts of two cables (of 6 and 9 November 2009) from Ambassador Eikenberry in Kabul. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “Obama Ignores Key Afghan Warning.”]

To its credit, even today’s far-less independent New York Times published a major story based on the information in those cables, while President Barack Obama was still trying to figure out what to do about Afghanistan. Later the Times posted the entire texts of the cables, which were classified Top Secret and NODIS (meaning “no dissemination” to anyone but the most senior officials to whom the documents were addressed).

The cables conveyed Eikenberry’s experienced, cogent views on the foolishness of the policy in place and, implicitly, of any eventual decision to double down on the Afghan War. (That, of course, is pretty much what the President ended up doing.) Eikenberry provided chapter and verse to explain why, as he put it, “I cannot support [the Defense Department’s] recommendation for an immediate Presidential decision to deploy another 40,000 here.”

Such frank disclosures are anathema to self-serving bureaucrats and ideologues who would much prefer depriving the American people of information that might lead them to question the government’s benighted policy toward Afghanistan, for example.

As the New York Times/Eikenberry cables show, even today’s FCM (fawning corporate media) may sometimes display the old spunk of American journalism and refuse to hide or fudge the truth, even if the facts might cause the people to draw “an erroneous and gloomy conclusion,” to borrow Gen. Abrams’s words of 43 years ago.

Polished Pentagon Spokesman

Remember “Baghdad Bob,” the irrepressible and unreliable Iraqi Information Minister at the time of the U.S.-led invasion? He came to mind as I watched Pentagon spokesman Geoff Morrell’s chaotic, quixotic press briefing on Aug. 5 regarding the WikiLeaks exposures. The briefing was revealing in several respects. Clear from his prepared statement was what is bothering the Pentagon the most. Here’s Morrell:

“WikiLeaks’s webpage constitutes a brazen solicitation to U.S. government officials, including our military, to break the law. WikiLeaks’s public assertion that submitting confidential material to WikiLeaks is safe, easy and protected by law is materially false and misleading. The Department of Defense therefore also demands that WikiLeaks discontinue any solicitation of this type.”

Rest assured that the Defense Department will do all it can to make it unsafe for any government official to provide WikiLeaks with sensitive material. But it is contending with a clever group of hi-tech experts who have built in precautions to allow information to be submitted anonymously. That the Pentagon will prevail anytime soon is far from certain.

Also, in a ludicrous attempt to close the barn door after tens of thousands of classified documents had already escaped, Morrell insisted that WikiLeaks give back all the documents and electronic media in its possession. Even the normally docile Pentagon press corps could not suppress a collective laugh, irritating the Pentagon spokesman no end. The impression gained was one of a Pentagon Gulliver tied down by terabytes of Lilliputians.

Morrell’s self-righteous appeal to the leaders of WikiLeaks to “do the right thing” was accompanied by an explicit threat that, otherwise, “We shall have to compel them to do the right thing.” His attempt to assert Pentagon power in this regard fell flat, given the realities.

Morrell also chose the occasion to remind the Pentagon press corps to behave themselves or face rejection when applying to be embedded in units of U.S. armed forces. The correspondents were shown nodding docilely as Morrell reminded them that permission for embedding “is by no means a right. It is a privilege.” The generals giveth and the generals taketh away.

It was a moment of arrogance, and press subservience, that would have sickened Thomas Jefferson or James Madison, not to mention the courageous war correspondents who did their duty in Vietnam. Morrell and the generals can control the “embeds”; they cannot control the ether. Not yet, anyway.

And that was all too apparent beneath the strutting, preening, and finger waving by the Pentagon’s fancy silk necktie to the world. Actually, the opportunities afforded by WikiLeaks and other Internet Web sites can serve to diminish what few advantages there are to being in bed with the Army.

What Would I Have Done?

Would I have had the courage to whisk Gen. Abrams’s cable into the ether in 1967, if WikiLeaks or other Web sites had been available to provide a major opportunity to expose the deceit of the top Army command in Saigon? The Pentagon can argue that using the Internet this way is not “safe, easy, and protected by law.” We shall see.

Meanwhile, this way of exposing information that people in a democracy should know will continue to be sorely tempting, and a lot easier than taking the risk of being photographed lunching with someone from the New York Times.

From what I have learned over these past 43 years, supervening moral values can, and should, trump lesser promises. Today, I would be determined to “do the right thing,” if I had access to an Abrams-like cable from Petraeus in Kabul. And I believe that Sam Adams, if he were alive today, would enthusiastically agree that this would be the morally correct decision.

My article from 2010 ended with a footnote about the Sam Adams Associates for Integrity in Intelligence (SAAII), an organization created by Sam Adams’s former CIA colleagues and other former intelligence analysts to hold up his example as a model for those in intelligence who would aspire to the courage to speak truth to power.

At the time there were seven recipients of an annual award bestowed on those who exemplified Sam Adam’s courage, persistence and devotion to truth. Now, there have been 14 recipients: Coleen Rowley (2002), Katharine Gun (2003), Sibel Edmonds (2004), Craig Murray (2005), Sam Provance (2006), Frank Grevil (2007), Larry Wilkerson (2009), Julian Assange (2010), Thomas Drake (2011), Jesselyn Radack (2011), Thomas Fingar (2012), Edward Snowden (2013), Chelsea Manning (2014), William Binney (2015).

Ray McGovern works with Tell the Word, a publishing arm of the ecumenical Church of the Saviour in inner-city Washington. He was a close colleague of Sam Adams; the two began their CIA analyst careers together during the last months of John Kennedy’s administration. During the Vietnam War, McGovern was responsible for analyzing Soviet policy toward China and Vietnam.