For 60 years, Cuba has lived under siege from the most powerful nation on earth, denying it basics like food, medicine and building equipment – anyone who cares about economic hardship must call for it to end.

By Francisco Dominguez*

Jul 17, 2021

In an evidently well-coordinated action, on 11 July 2021, groups of opponents of the government staged demonstrations in several Cuban cities, notably Havana. Within seconds of the event the world’s mainstream media, including, of course, the media in the UK, were in full swing magnifying the event.

Such social outburst is an unusual event in Cuba and even more surprising were the intensity and violence deployed by the protestors (vandalism, aggression against officials, attacks on public buildings), reminiscent of similar protests in Venezuela in 2014 and 2017 and Nicaragua in the coup attempt of July 2018.

It was clear these opposition groups were carrying out the well-known Venezuelan tactic of guarimba (violent and media-oriented street disturbances). The protests were immediately responded by mass mobilisations in support of the revolution across Cuba, pictures of which were presented as anti-government by media such as the Guardian (though it subsequently rectified the mistake).

The reasons for the original street protests were scarcity of food, medicines, electricity supply and fuel that burden the daily life of the island’s 11 million Cubans with severe difficulties. These include food and fuel queues, electricity blackouts, fall in income, and general economic hardship.

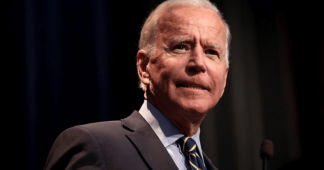

Cubans have genuine concerns about a deteriorating socio-economic reality in their country, brought about mainly by the drastic intensification of the U.S. blockade under Donald Trump. Biden, despite electoral promises to restore the good relations under Obama, has done nothing to alleviate this situation – and its impacts have dramatically heightened with the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The pandemic has decimated tourism in Cuba, the island’s main hard revenue earner. It also interfered with trade and slowed the economy. But in addition to these impacts on income and food, Cubans also had to face shortages of medicine – severely impacted by the effects of the embargo – which has contributed to a health crisis, notably in Matanzas.

The election of Donald Trump led the U.S. to fully reverse the timid but positive decisions to alleviate aspects of the blockade on Cuba under Obama. Under Trump, the United States imposed an additional 243 unilateral coercive measures (aka sanctions), including adding Cuba to the U.S. list of states sponsoring terrorism, which amounted to a brutal and entirely unjustified intensification of the U.S. aggression against the Cuban people.

The sanctions target every aspect of Cuba’s economy. They prohibit trade with businesses controlled or operated by and or on behalf of the military; ban U.S. citizens from travelling to Cuba individually and as groups for educational and cultural exchanges; withdraw most of its staff from the U.S. embassy in Havana leading to, among other things, the suspension of visa processing; allow U.S. nationals to enter into litigations against Cuban entities that “traffic” or benefit from property confiscated by the Cuban revolution since 1959; prohibit cruise ships and other vessels from sailing between the U.S. and the island; ban U.S. flights to Cuban cities other than Havana; suspend private charter flights to Havana and bar U.S. citizens from staying in establishments linked to the Cuban government or the Communist party; curb the sending of remittances from the U.S. to Cuba (Western Union had to shut down its operations in the island); seek to block the flow of Venezuelan oil to Cuba through applying sanctions to shipping companies and Cuba’s and Venezuela’s state oil companies; ban Cuban officials from entering the U.S. for alleged complicity in human rights abuses in Venezuela, and much more.

These are all in addition to existing conditions which make it very difficult for international businesses which operate in the United States to also do business with Cuba, something which means the blockade in reality is not just a two-way affair. The sanctions aim to cause the maximum hardship, exactly as the blockade was designed to do in the infamous 1960 U.S. State Memorandum 499:

“The only foreseeable means of alienating internal support is through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship […] every possible means should be undertaken promptly to weaken the economic life of Cuba […] a line of action which, while as adroit and inconspicuous as possible, makes the greatest inroads in denying money and supplies to Cuba, to decrease monetary and real wages, to bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow of government.”

By 2018, the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) reported that the U.S. financial and trade embargo on Cuba had cost the country’s economy US$130 billion.

The Covid-19 pandemic has, additionally, taken a vicious extra toll on the Cuban economy. The arrivals of foreign tourists declined by over 90% in the period 2020-2021, wreaking havoc in the economy. Revenues from vital hard currency were cut off, and the vibrant services sector that had emerged with the expansion of tourism was almost entirely shut down. The total number of foreign tourist arrivals in 2019 was 4,275,558 whereas in 2020 was only 1,085,920; but the fall by May 2021 (January to February) was on average 96%.

It would be naive if not disingenuous to believe that, as part of Trump’s sanctions strategy against Cuba, officials and strategists of the U.S. machinery did not include a plan for destabilisation. We are doubtlessly witnessing part of this today with the co-ordinated violent street demonstration combined with a U.S.-led social media offensive. For years, many millions have flowed from the U.S. to opponents of the Cuban revolution – under Trump, this number increased, and the impacts of this at a time of broader crisis can’t be underestimated.

The dreaded USAID and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) had, since Donald Trump’s coming to office in 2017, been funding at least 54 groups opposed to the Cuban revolution. Their funding amounted to nearly US$17 million, but the figure is likely much higher when you consider that ‘democracy-building strategies’ are exempt from disclosure under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

U.S. funding of ‘democracy-promotion’ in Cuba is shrouded in secrecy and the recipients of this funding are not known, nor is known how they use it. USAID and NED fund digital journalists, ‘human rights’ promotion groups, citizen participation organisations, hip-hop singers and rappers, academics, artists and so forth. Not included in the 54 groups are contractors and subcontractors, nor how many Cubans receive money, but the Directorio Democratico Cubano, for example, reported paying 746 contractors and 1,930 subcontractors in 2018.

That is, one opposition organisation out of the 54 known USAID-funded in Cuba reports having paid over US$150,000 to more than 2,500 activists. This kind of funding can help to explain the high degree of homogeneity and co-ordination exhibited by the timing, places and non-peaceful nature of the July 11 demonstrations.

It is no surprise that Cuba, as many a Latin American nations before it, faces an assault on its national sovereignty. After all, we have seen only in recent years how the coup d’état in Bolivia played out, with full Western backing. These events are most often executed from within but led, organised and financed from without.

Those without include from USAID and NED, but also more vocal and deliberate right-wing elements such as Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz and the Miami Republican organisations at home, as well as the likes of Bolsonaro, Alvaro Uribe and Luis Almagro on the wider continent. Their aim is to act as defenders of ‘democracy’ and establish narratives in the international media. Marco Rubio has made an appeal to president Biden to intervene against Cuba and has lambasted the Black Lives Matter movement for issuing a statement supporting Cuba and condemning the U.S. blockade.

Conversely, the governments of Argentina, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Mexico, the ALBA group of countries, but also Lula, Dilma Rousseff, Pedro Castillo, the Puebla Group and the Sao Paulo Forum have made it clear they oppose external interference in the internal affairs of Cuba. They have demanded an end to the blockade as a pre-condition for the necessary improvement of economic circumstances for the people of the island. The international lines on this subject between progressives and conservatives couldn’t be clearer.

Not once has a U.S. intervention (under any guise) brought anything resembling democracy to Latin America. Time and again, its efforts have resulted in dictatorships, mass privatisations and brutal violence meted out against the poorest. By contrast, despite its many problems and imperfections, in 60 years the Cuban Revolution has become a beacon of solidarity and generosity around the world – undertaking to support the cause of justice even while its own circumstances have often been difficult.

In recent years, Cuba and Venezuela’s joint medical programme, Operation Miracle, led to over 4 million free of charge eye operations to poor people with cataracts and related eye ailments. Its medical internationalism has meant that to date, ‘Cuba has sent some 124,000 health professionals to provide medical care in more than 154 countries’ and, since March 2020, more than 3,700 Cuban health doctors, nurses and technicians have volunteered to go to 39 countries (including Italy) to help fight the Covid-19 pandemic.

The only long-term solution to Cuba’s woes is the immediate and unconditional lifting of the U.S. blockade. That is the demand of the world, expressed by every U.N. General Assembly since the 1990s, it is the demand of international law, and it is the demand of justice.

Published at tribunemag.co.uk