By Malvina Alexopoulou *

The Necropolis of Cairo is in danger, the historic Cairo, which is a UNESCO World Heritage site, is sending an SOS signal in the face of an expensive “modernization” project of the city with new major central roads, bridges, and viaducts. While these improvements will enhance traffic flow in the vast and congested metropolis, home to approximately 20 million people.

What will happen to the Necropolis? What will become of the inhabited cemeteries of Cairo, which simultaneously accommodate the living and the dead? What will happen to the historical and non-historical tombs located in the “city within a city”?

The Necropolis of Cairo

The southern Necropolis was not always located in the south of the city of Cairo. In the days when Cairo was confined to the area around Fustat, it was crossed by roads and surrounded by: • The natural barrier of Mukattam with hills to the east.

- A wetland area to the west

- An immense land unsuitable for burials, which included the sulfur springs of Ayn al-Sira (now a resort).

- And the Basatin factories to the south.

The Fatimid Caliphate ruled Egypt for two centuries (969-1171), establishing a new capital north of Fustat called al-Qahira, which gradually evolved from a royal city into a true metropolis. The caliphs, reviving ancient regional traditions, built luxurious mausoleums in many different locations: the first in the regular cemetery of Qarafa and later along the road from Cairo to Fustat, now known as the Sayyida Nafisa cemetery.

(Source: Architecture for the Dead, 2007, p. 22)

However, since the 1980s, the situation has completely changed. A wave of modernization projects has turned Qarafa into a network of high-speed highways and bridges, degrading the old central roads. Meanwhile, in the north, Salah Salem Road has cut off Qarafa from the city, leaving the historic Sayyida Nafisa cemetery completely isolated. (Source: Architecture for the Dead, 2007, p. 22)

The Caliphate of the Fatimids built several significant and insignificant mosques, mausoleums, and palaces, which, however, due to their descriptions and excavations, constitute clear evidence of the new relationship that developed between the living and the cemeteries, a relationship that continues to this day. On the one hand, using cemeteries as vacation spots and, on the other hand, residing there, with the inhabitants working hard in the urban core.

Urban Analysis

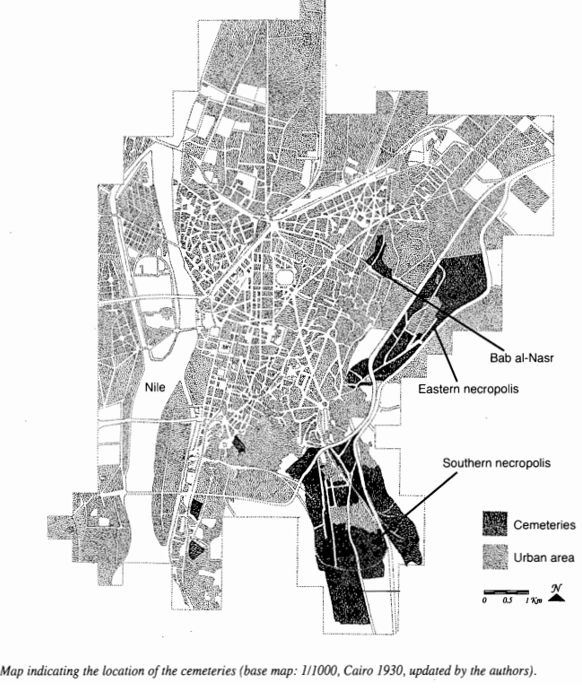

Initially, the Cairo Necropolis was located at a significant distance from the city. Its placement in this area was chosen not only for sanitary reasons but also due to the vast, sandy, unused land. This area could provide the necessary materials for the construction of tombs and gradually built monuments. The study of Cairo’s urban planning extended to the boundaries of the two necropolises. Despite this, it was deemed necessary to establish regulations within the existing cemeteries. Given the extensive residential areas and enclosed family tombs, a reassessment and addressing of this situation became necessary, both at a practical level and through a new institutional framework. This construction process continued for many decades and, in fact, we could say it continues to this day.

The spatial structure of the area does not coincide with any type of zoning plan. It is a chaotic, labyrinthine web. The density of construction was higher in areas where significant religious monuments were built, due to the burial of important individuals for their respective eras. Additionally, most of the constructions in these areas were large in size and had special architectural value. These areas, due to the importance of their deceased, also served as places of pilgrimage and prayer. On the contrary, in other more “humble,” “insignificant” areas, construction was sparser and on a smaller scale, consisting of simpler structures.

Between the necropolis and the city of Cairo, the central avenue of Salam Saleh is located. In the past, this was the boundary separating Cairo from the Necropolis. However, today we observe that the city has expanded so much that it “embraces” the necropolis perimeter. Within it, there were roads almost from the beginning of its creation. Some of these roads have sufficient width to accommodate vehicles, which is indeed the case. However, the majority of them are very narrow and labyrinthine in shape due to the disorderly construction of both tombs and residential annexes (according to Vergina Tzani). In 1992, after the catastrophic earthquake that struck Cairo, the City of the Dead was inhabited by new residents, and its population is approximately half a million.

The Cairo Necropolis now consists of the ruins of ancient mausoleums and is under state protection.

The Living and the Dead

The factors that led to the creation of this “city of the living and the dead” over the centuries are very interesting but also quite complex. The entire development of this historical area emerged from economic, political, social, urban planning, and religious components.

When we refer to the Cairo Necropolis, as mentioned above, we essentially refer to the two cemeteries of the city, the northern and the southern one. These two cemeteries have existed for hundreds of years under a unique operating regime. However, this regime does not align with the modern living conditions of the millions of people living in this area. Naturally, these cemeteries function as sacred burial grounds, as one would expect. Within this complex, the world of the dead and the living coexist, comprising both tombs and residential annexes that form a vast subcity. This image becomes even more distinctive due to the presence of a large number of religious monuments.

The intense and rapid urbanization since the 1950s and the economic inability to afford housing due to the high cost of living forced people to find shelter in the medieval Islamic necropolis. Children, young people, and the elderly, estimated to be hundreds of thousands of people, have been experiencing the tragic reality in appalling living conditions for decades, without any municipal services or even an official address. Furthermore, some residents even work as marble craftsmen for the construction of tombs.

Apart from residences, some graves have been converted into small shops and glassblowing workshops where traditional glassware such as glasses, vases, and other objects are produced in traditional ovens. The eerie tranquility of the necropolis is only interrupted by itinerant street vendors who advertise their wares, which they transport on carts pulled by mules.

According to El Kanty and Bonami (Architecture for the dead, 2007), there are people who take care of the graves for a fee, digging new tombs and selling flowers to all those who visit their loved ones every Friday. “Living with the dead is a very easy and comfortable affair,” says 47-year-old Nasra Mohamed Ali, continuing, “It is the living who will harm you.”

The masterplan that jeopardizes centuries-old history – The Necropolis sends an SOS

“It’s a double trauma. First, my mother died last year. Now, I am digging up her fresh body and the remains of my grandparents, putting them in bags and driving to re-bury them in new tombs in the desert,” said Iman, crying.

And she is not the only one crying or unearthing her dead.

Lately, the Egyptian government has been clearing a large area to create space for new main roads and flyovers, which, it claims, will improve traffic flow in the enormous, congested metropolis. These residential projects will also connect the heart of the capital to a new administrative center being built 45 kilometers to the east, a massive project costing billions of euros.

These constructions are part of an effort to modernize Egypt. Since President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi took office in 2014, a total of 7,000 kilometers of roads and approximately 900 bridges and tunnels have been constructed across the country, with military contractors executing a significant portion of the projects. Authorities insist that none of the many documented monuments in this old section of Cairo have suffered or will suffer any damage and that the required respect for the most important tombs is demonstrated. “We will not do anything to harm the tombs of the people we admire or the monumental areas.”

“We are building bridges to avoid it. We should not provide arguments to those who want to tarnish our efforts. Although officials claim that the affected tombs mainly belong to the past century and that compensations are provided to the relatives of the deceased, there is a public outcry over the loss of precious architecture and a unique cultural heritage in six historic cemeteries with magnificent marble tombs engraved with Arabic calligraphy. Members of royal families, famous Islamic scholars, poets, intellectuals, and national heroes are buried in these cemeteries, which are now at risk.

Save Culture and Art!

Mustafa El-Santek, a distinguished physician and university professor, has recently become a savior of historic cemeteries with the help of volunteers. He searches in the ruins of demolished cemeteries and tries to save whatever he can. “I am deeply saddened to see the tombs of Historic Cairo being removed. We can learn our history through cemeteries,” he emphasizes while saving tombstones and other art objects. “They are of inestimable value. I believe that these treasures should be preserved.” He recounts how he recently glanced at a stone plaque, built into a demolished wall, which contained engravings in Kufic script, an early style of Arabic calligraphy, and conducted research at the Imam Safi cemetery, opposite the Sagyeda Nafisa. His team carefully removed the tombstone and found that it had an inscription for a woman named Ummama, dating back to the 9th century (the epitaph column has now been handed over to the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, with the hope of being displayed in a museum).

Some residents have already received government proposals to relocate to rented apartments built on the outskirts of Cairo. “Unfortunately, Cairo will lose a valuable heritage,” says Kanty, an architect studying the “City of the Dead” and its residents, along with other historic cemeteries, since the early 1980s. However, she does not accept the arguments of government ministries for a new general plan for Cairo. “They don’t know the meaning of heritage, the meaning of history. This is an environment where all previous rulers have preserved from antiquity to the present era.” Kanty is trying to stop the process, but so far without success.

“Even the approach to UNESCO did not yield results, although the organization expressed concern that tomb demolitions and road construction could have a ‘significant impact on the historic urban fabric’ of the area. The remains of Queen Farida, the wife of King Farouk I, who was overthrown in a coup in 1952, were transferred to a mosque after the destruction of her tomb. Additionally, the tomb of Abdallah Zoudé, a 19th-century calligrapher whose works adorn the two most revered mosques in Mecca and Medina, was demolished. There have been some limited victories for activists, such as a recent campaign to save the tomb of the great Egyptian novelist and intellectual of the 20th century, Taha Hussein, when his tomb was marked with a red ‘X’ for demolition. However, conservatives point out that the integrity of the area is being lost because the remaining tombs and monuments will be buried underground or surrounded by new roads.”

Extra Bonus of Historical Devotion: The Mosque-Mausoleum of Sayyida Nafisa

The Muslim mosque-mausoleum of Sayyida Nafisa originally belonged to the great-granddaughter of Prophet Muhammad, the daughter of Al-Hasan, son of Imam Ali. Nafisa relocated from Medina to Cairo in 809 AD and passed away in Cairo in 824 AD. It is said that Nafisa constructed her own tomb because she knew her time was approaching. Every day, she would enter the tomb and offer prayers there. She was known not only for her abstemiousness and piety but also for her religious teachings. Furthermore, Nafisa provided education to young girls and women during her time.

The particular mosque was initially built by the governor of Egypt, Hakam (Ubaydullah bin Sirri bin al-Hakam), and later underwent renovations in 1089, 1371, and again in 1897.

Apart from attracting numerous devotees, it continues to attract young couples who often celebrate their weddings there and seek the blessings of Sayyida Nafisa.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.