Isla Bermeja, only noticed missing in 2008, may have cost Mexico millions in oil revenue

By Shannon Collins

June 28, 2021

First appearing in a Spanish compendium of all the islands of the world in 1539, Bermeja has flummoxed sailors, fishermen and politicians since it seemingly vanished from the ocean around the turn of the 21st century.

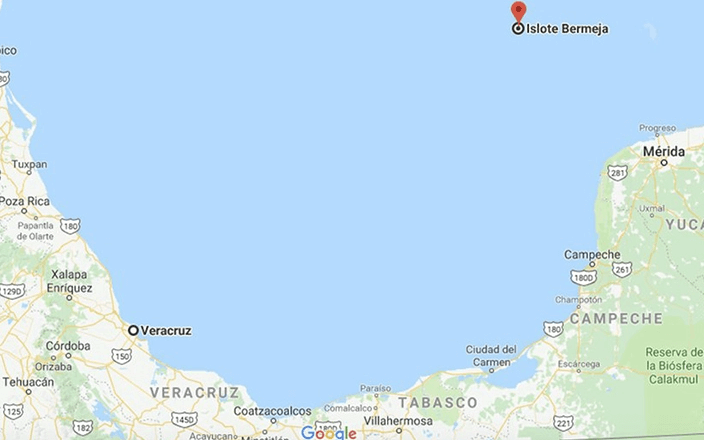

22°33’N, 91°22’W. Take a boat to these coordinates and you are almost certain to find nothing but empty water and open skies despite the fact that, dating back to the 16th century, this phantom islet in the Gulf of Mexico was clearly visible on maps and charts.

Isla Bermeja’s dematerialization only became apparent over the course of negotiations between the governments of Mexico and the United States in 2008 and 2009 over who had drilling rights to parts of the Gulf of Mexico, in which the phantom island was considered crucial for determining national marine boundaries.

“Isla Bermeja was a controversy because it was a key area of the Exclusive Economic Zone in the Gulf of Mexico,” geographer and islands specialist Israel Baxin Martínez explains. “There were official searches around this time to see if there was some remnant of this island because the expansion of this zone for Mexico would mean an abundance of oil.”

Off the north coast of the Yucatán, it would have been the northernmost Mexican island in the gulf. As a result of its absence, Mexico lost rights to a maritime area that was believed to hold 22.5 billion barrels of oil.

It has been speculated that the island disappeared as a result of natural geographic shifts in the ocean floor and rising sea levels that have already swallowed remote islands in Hawaii, Japan, and the Arctic.

It could also be, of course, that the island never existed and that its appearance on early maps was merely the result of erroneous observations by cartographers.

With such a plentiful stock of black gold on the line, and the complex political latticework that oil negotiations necessarily entail, conspiracy theories about the cause of the island’s disappearance abound.

It is even common chatter among fishing communities along the coast of the Yucatán that the island was destroyed deliberately to allow the United States to eat into the Exclusive Economic Zone.

However, when negotiations began in 2009, oil production rates had been dropping — or failing to increase — every year since 2004. In spite of this, oil revenues count for 10% of Mexico’s export earnings, and therefore are a significant contributor to national GDP.

Notwithstanding the continuing global slump in oil demand as a result of the rise of sustainable fuel options and a more widespread awareness of the damaging effects of drilling for and burning crude oils, the loss of the territory to the U.S. represented a significant blow for economic expansion.

“It’s a conspiracy theory, of course,” an unmoved Martínez says.

Yet the layman’s whisper has seeped into the political chat at large: in November 2008, six senators from the then governing National Action Party (PAN) raised questions about Isla Bermeja, citing suspicions that the island had been made to vanish deliberately by American powers in order to give the U.S. more leverage in negotiations over marine territory.

This, however, is a more-than-suspect allegation. It is scarcely believable that an entire island could be destroyed or obfuscated from the map without somebody noticing, and there is already a precedent for confusion around the existence of small islets.

In the Pacific, for example, Martínez cites islands that, through issues with cartography or nomenclature, either do not exist or are existentially confused. He cites as examples cartographical inaccuracies appertaining to the Isla de Cedros and the Revillagigedo Islands southwest of the southern tip of Baja California, a large archipelago famous for its endemic flora and fauna.

“Conceptually,” Martínez continues, “we notionally believe that everything that is mapped must exist. So, because the island was mapped in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, the assumption was that the island existed, and the map record confirms it.”

In these cases, Martinez says, the existence of the islands was “a continually unconfirmed truth,” which is as much to say that once an entity is mapped, its existence is assumed and replicated without question.

Bermeja, however, is a little different. Historically, the island was mentioned in the cartography of explorers in the 18th century, but it is additionally mentioned in other documents, including a number of official inventories at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century — some of which were government inventories.

“The question with Bermeja in particular is that it’s not just mentioned in cartographic history,” says Martínez. “It has a much larger backlog of studies and a presence in the official inventories.”

Since 2009, there have only been four official expeditions to find Bermeja, alongside a handful of journeys by enquiring journalists and the generally curious.

In the last decade, TV Azteca and the National Autonomous University launched maritime research campaigns to locate the territory, but the missions came to the same conclusions as those sponsored by the government: that the island does not exist and that there are no vestiges of such a body of land in the area.

It is telling that there was little interest in the island until it was believed to have been taken away; like a child with toys, the Mexican cultural consciousness was uninterested in an uninhabited island miles into the gulf until it was no longer there.

“Culturally, what we see with Bermeja, as in many other cases, is that people don’t care about what they’ve got, but they do care about what they’ve lost,” Martinez reflects. “People are jealous of what has been taken from them, but they refuse to do anything with what they already have.”

And therein — perhaps — lies a much greater truth, one that has little to do with disappearing islands and much more to do with the unquestioned lies we build up around us in order to perpetuate the myths of who we believe ourselves to be.

Shannon Collins is an environment correspondent at Ninth Wave Global, an environmental organization and think tank. She writes from Campeche.

Published at mexiconewsdaily.com