In researching the biography of Michel Raptis, known as Pablo in the Trotskyist Fourth International, I came across Dimitris Livieratos’ account of the arms factory Pablo ‘authored’ in Morocco during a grim phase of the Algerian War when the Algerians were starved of arms. For a man who professed Tolstoyan-Christian attitudes towards violence that was quite a step politically. That’s another story. Then there were all the organisational difficulties and dangers – this was a time when the French version of the CIA were busy killing collaborators with the Algerians. Livieratos’ little book gives easily the best account of this relatively unknown chapter in the Algerian revolution. in its way it is a minor classic. Here are some notes on the book…

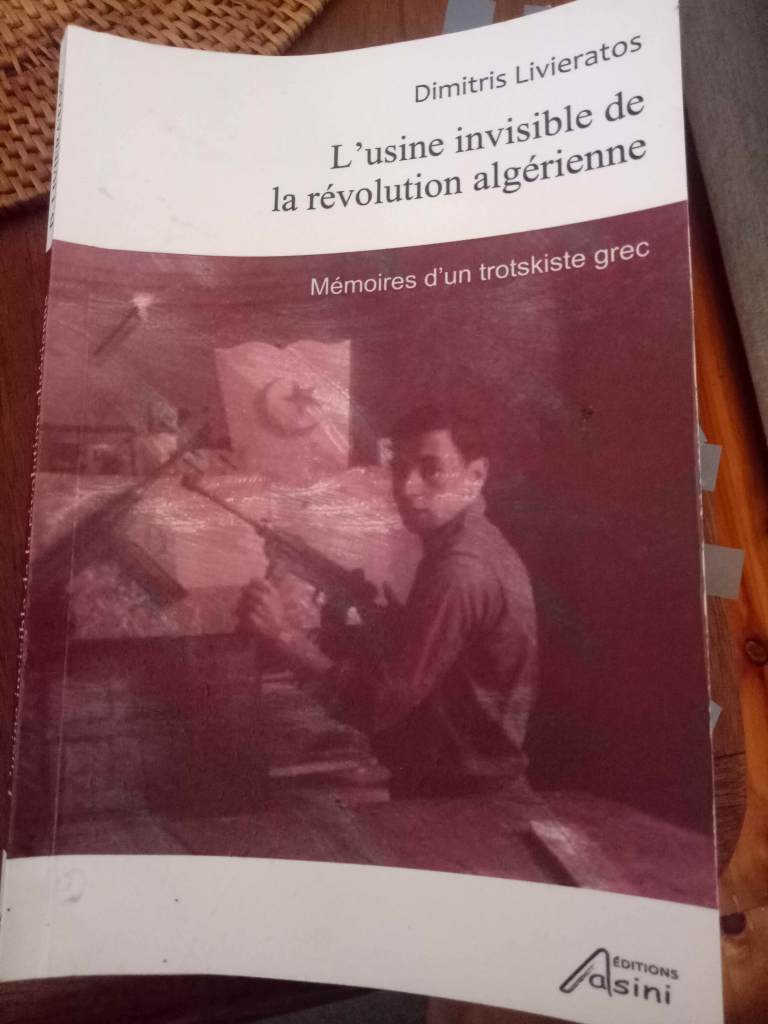

Dimitris Livieratos, a Greek comrade of Pablo’s, served as the chief organiser on the spot in Morocco and shuttled between Casablanca and London for his meetings with Pablo – and naturally Hellie [Pablo’s indomitable and outspoken wife] who was always present. He has given us a frank and episodic account of the whole experience of setting up the factory producing submachine guns.[1]. It was originally written in the mid-1960s on the basis of notes he’d made in 1961 but not published until 2001. The original was in Greek and it wasn’t until 2012 that a French version appeared.

For Livieratos the honour of the European Left in relation to the Algerian War was saved by the Christian Leftists around the magazine Temoignages Chretiens, a few intellectuals like Francois Jeanson and the Trotskyist PCI. These few men and women offered their support to what was an unambiguously just cause. For the Trotskyists the key man was Pablo, as Livieratos acknowledges:

The Greek Michel Raptis (Pablo) who made the decisive link with the independence movement was then head of the, Fourth International. The issue of our support soon went beyond the political and theoretical level and the question was posed of the extent of our practical support. There were some hesitations on this subject. But the majority finally pledged their support – to the ‘ultimate consequence’.[2]

The ultimate consequence was of course to be shot or blown up by the operational arm of the French secret service, La Main Rouge, who by then had either killed or scared off arms suppliers to the Algerians.

Accepting the risks, Livieratos was a good soldier. Although he could get impatient with Pablo – he sometimes thought he was too careful – he never questioned his leadership. He assumed responsibility for the management of the 30 or so internationals that Pablo and Sal Santen recruited and sent to work in the submachine gun factory. In addition, the Algerians liked and trusted him and informally incorporated him into the overall management of their other arms factories in Morocco – these were making grenades and mortars.

Some of the Algerians became his comrades. In fact, the most affectionate portraits in the book are of Algerians, not his fellow internationalists. The two he was closest to were Ibrahim and Mourad (Livieratos uses only their first names). Ibrahim is an old Algerian communist who insisted on calling everyone ‘comrade’ when the universal term of address was the Muslim ‘brother’. He had broken first with the French Communist party (PCF) and then the Algerian Communist party (PCA) over their refusal to back the armed struggle for independence. The PCA’s later conversion did at least offer him some consolation. As for Mourad, he occupied the other end of the political spectrum inside the FLN as a nationalist. Mourad was hostile to socialism and didn’t believe an independent Algeria would be ready for democracy. Something of a loner and dissident who had been downgraded but was now rising again in the ranks, Mourad told Livieratos that he didn’t intend to live in Algeria after independence. As it was, he was no sooner accepted back into the leadership than he died in an accident before freedom was attained.

To establish the factory producing what was a Belgian copy of the French pistolet mitrailleur MAT 49 was a complex and extraordinary task – especially doing it quickly and secretly. It was something which the GPRA/FLN initially thought beyond their capabilities. It meant sourcing the machines and materials in Europe, shipping them to Morocco, transporting them to a secret location (a former jam factory in an orange orchard as it turned out), and finally recruiting a skilled workforce. All this had to be done without details fatally leaking to the French secret police. In Morocco itself, French spies and informers were numerous, so once the factory was set up, the workers would be virtual industrial prisoners granted only very limited leave. The first version of the factory built in 1959 had to be abandoned and the machinery moved overnight when a high functionary in the FLN defected to the French in April 1960.

Understandably once the factory began operations, morale was a problem for the ‘entombed’ workers, both Algerian and international. As the whole operation was secret at the time and likely to remain so for some time afterwards, there was little or no glory as compensation. The days were long and boredom was a constant problem. Many of the workers involved – and not just the Algerians – wanted to serve the revolution as armed insurgents. Being unacknowledged factory workers, slaving 10 hours a day in a former marmalade factory in the backblocks of Morocco, was not the heroic role they thought they were signing up for.

Livieratos breaks down the 300 Algerians working in the arms factories into two distinct groups – those who had tasted life outside Algeria and those who came direct from the villages of the plains and mountains of that country. In the first group were the ‘ancients’, those who had worked in the already existing factories for more than a year and were conditioned to the long hours and lack of freedom. These veterans were supplemented by the ‘newly arrived’ workers from Paris, Lille, Marseilles or the French prison system, who expected to be fighting for the Revolution but found themselves imprisoned in the humdrum life of the factory, yet who were nevertheless usually good-humoured. These workers spoke French as well as Arabic, were generally left-wing and had shed their religion. The other half were peasants from the villages, displaced by the war, resigned, patient and religiously observant. The conflicts between the newly arrived proletarians from France and the peasant brothers was the most marked division – ‘while the French are killing us, they pray’, one of the Franco-Algerians observed of the men from the djebells. The Algerians workers were incidentally almost all young, between 18 and 22.

The international volunteers were not all members of the Fourth International. Livieratos is scornful of the ‘excuses’ many of the leaders and the members of the European sections made for not sending volunteers. For him it was a symptom of the ingrained eurocentrist, talking shops, that much of the International had become. Because of this abstemious support, Pablo and Santen were thrown back on depending on non-member volunteers, most of whom were impatient with any discussion of high-blown politics but supported the cause of Algerian freedom. Among such volunteers was the Dutchman and veteran of the Dutch World War II resistance, Albert Oeldrich, who we will meet later in a worse light. He was a highly skilled designer and engraver and was deeply involved in setting up the factory and sourcing equipment. Livieratos calls him ‘the old adventurer’. At one stage Pablo is forced to intervene to read Albert the riot act, to stop him going freelance and making side arrangements with ‘Victor’, the boss of the Algerian operations in Morocco, without going through Pablo or Santen. It was a trait that would soon or later bring down Pablo and Santen.

By Livieratos’s account these thirty internationals came from nearly a dozen countries, mostly skilled men necessary to the setting up and maintenance of the factory. We learn something of the lives and character of only a handful, and in another sign of Livieratos’s internationalism, it is the two Jamaicans who get the fullest treatment. Altogether the internationalists were not a completely happy band of comrades, as some develop doubts about the International’s line of unconditional support for the Algerians. One of the Englishmen in particular, has no sooner arrived than he wants to leave. Livieratos has to argue long and hard to secure the agreement of the Algerians for this ‘desertion’. But the main conflict among these international proletarians is around the model of management for the factory. Workers self-management or Lenin’s favoured one-man management. The Argentinians insist on collective, democratic management but the Europeans – the Dutch chief among them – are more favourable to traditional, top-down direction. In the end a compromise is agreed: regular general meetings, but day-to-day management to be devolved to a triumvirate of the three most skilled men.

For the Algerians decision-making appears to have been by general assembly but the democracy was more consultative than determinative. Brothers could raise whatever issue they liked and say whatever they liked, but any prior factional organising or caucusing was absolutely forbidden. Despite all the toing and froing and arguing, it was the leaders who made the final decisions, usually based on what they have heard. At times they would put an issue to the vote to better gauge what is acceptable and then accept the result. It appeared to be more participation than autogestion. Nevertheless, their meetings are frequent and long – up to 12 or 14 hours – and frequently stormy. The internationals attend these meetings but only speak when invited. The meetings are in Arabic with a smattering of French. Livieratos learns some basic Arabic and so is able to get the gist of the arguments.

At the factory, life was not all grim and argumentative. An esprit de corps develops. True at all of the factories the workers are shut in and the perimeters patrolled by frequently officious Algerians soldiers, but at Souk al Abra there is a a swimming pool and the more worldly and travelled Algerians teach the boys from the interior how to swim. There is also much fraternisation, reading and talking:

Those who weren’t required at their posts sat around on their blankets under the trees… We talked of all or nothing, of Brigitte Bardot or dialectical materialism. Day after day we swapped stories from all corners of the globe.

Weeks, dates, time itself, lost their importance.[3]

The factory operates until the ceasefire in March 1962, producing more than 5,000 submachine guns. In July 1963 Livieratos is invited back to Algeria as an official guest for the first anniversary celebrations of independence. In the march-past on the 1st of July in Algiers, seated on the podium for special guests, he is excited to see a battalion of soldiers pass by brandishing their PMs aloft. His internationalist labour has not been in vain although it does appear that by 1961 the FLN’s arms drought had been solved by huge shipments from China and Eastern Europe. There was nothing the French navy and La Main Rouge could do about that.

No sooner had he finished setting the factory on foot than the FLN approached Pablo for help with another project. Ironically it was to be an operational failure but very public, very visible – and a signal political success.

[1] L’usine invisible de la revolution algerienne, memoires d’un trotskiste grec (Editions Asini, Athens, 2012)

[2] L’usine invisible p.27

[3] L’usine invisible, p.131

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.