by H. Michiel, September 2016

On the occasion of the publication of the Dutch translation of Stiglitz’ book on the euro, I wrote a presentation of it for our website www.andereuropa.org (a joint initiative by Flemish and Dutch left opponents of the EU). Apart from a fairly long summary of its contents, it also contains an appreciation as for its significance in the actual political context. This could possibly have some relevance for our discussions at the Plan B and Lexit gatherings in Copenhagen in November; I will therefore briefly discuss why I think the book is important:

- Social democrats, greens, trade union responsibles should be confronted with the findings of a ‘moderate’, who moreover is favourably disposed towards them;

- Stiglitz’ book should also provoke some self-questioning by the majority of the European radical left, who mostly depict an exit from the Eurozone in cataclysmic terms.

Left critics will have no problem to show that Stiglitz is an ‘ordinary’ neo-keynesian, whose thinking is not that different from mainstream economic theory. He makes no secret of his credo in ‘inclusive capitalism’. When he speaks of full employment, it is in the sense of the NAIRU, which in fact subordinates a social need to a macroeconomic model. He promotes the carbon emission markets (though with a sufficiently high price per tonne)and is in general cautious when doing macroeconomic proposals not to disturb the market more than necessary. His critique of the Troika pertains to its policy; its legitimacy is not really questioned in the book. He presents the neoliberal principles underlying the construction of the euro mainly as a kind of thinking deficiency, reflecting the ideology of the time when the euro was designed (although he does not exclude that a political agenda ‘played some role’). There is no question that Stiglitz is not Chomsky.

Expert advice for social democrats and greens…

But the importance of his book lies elsewhere. In Europe, Stiglitz is considered as a social democrat, and as he mentions in the book, he offered advice to several social democrat governments and is befriended with several of their leaders (excluding the Blairs, Schröders etc.). For a few euros, European social democrats can procure with this book a ‘high level advice’ of an internationally renowned expert, who is more than favourably disposed towards them. The same can be said of green politicians and responsible persons in the trade unions, who most often get their insights in the European situation from political leaders in the ‘befriended parties’. In fact, responsible politicians and leaders in these organizations could not disregard a thoroughly argued study which concludes that, if no fundamental reforms are urgently introduced, a disruption of the Eurozone is better than going on with it. This friend of social democracy gives even free advice for Eurozone countries which would envisage divorce, in order to reduce as much as possible the inevitable turmoil it would involve.

Now, we should not have too many illusions in the ‘appeal’ Stiglitz’ verdict will exercise on parties, and up to now, I didn’t come across reactions from these quarters. I am afraid most of them think what ex-‘president’ Van Rompuy said recently (De Tijd, 13 September) about the situation in the EU: “I think we better continue muddling on, albeit that it is not brilliant”.That’s why it could be a good idea for our movement to try to confront politicians with these ‘disturbing’ findings of a Noble prize winner (OK, it’s the Swedish National Bank’s prize), to provoke debates on it where possible, to popularize its conclusions for a broader public.

… but also some brain food for European radical left

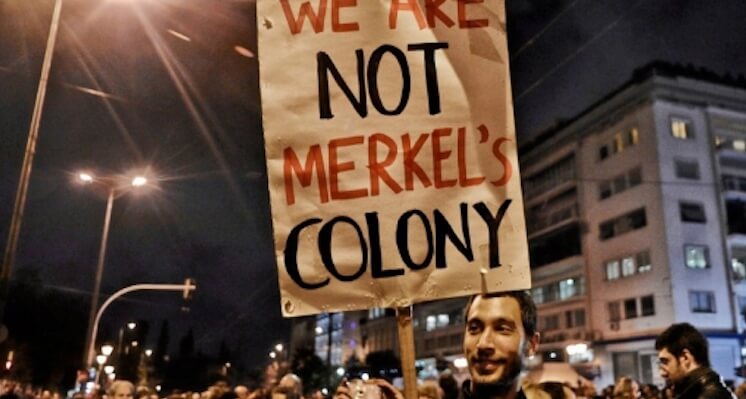

There is another, more restricted public for which Stiglitz’ book should provoke some self-questioning: the majority of the European radical left. It is quite remarkable that the moderate Stiglitz, who as an ex of the World Bank has had some first-hand experience with countries in troubled economic waters, is much less reluctant to ‘preach the benefits of divorce’ (and as already said, offers some practical ideas for it) than are most radical and marxist economists and authors.Que faire de l’Europe?, a joint publication of Attac France and Fondation Copernic (2014) is rather representative for the positions (sometimes called ‘left europeanism’) which have been taken in the European left with respect to the role of the euro. My intention is absolutely not to contribute to the creation of more ‘camps’ and division lines in the European left, and I highly estimate and have learned a lot of authors as the ones of the study mentioned above (to mention just a few: Thomas Coutrot, Michel Husson, Pierre Khalfa, Catherine Samary, … It should be added that the positions in the book are not necessarily shared by all authors.). But it raises questions when the moderate Stiglitz takes vis-à-vis the euro a similar position as Costas Lapavitsas, Cédric Durand, Frédéric Lordon…, a minority position within the left which is often judged irresponsible by the majority. The latter reproaches the former to minimise the problems of an exit: debt will rise due to the devaluation of the new currency, and the latter is no guarantee that competitivity will improve; there will be an ‘infernal cycle’ of devaluations, “making the EU and the euro the main cause of ‘our’ problems will inevitably contibute to a wave of nationalism.”, breaking with ‘Europe’ (although the eurozone is meant) is looking for solutions in its own little corner, suggesting that staying inside is a condition for real internationalism.

It must be added that the arguments of the minority are not always presented in a very correct way. Often, it is suggested that they think of an exit as a panacea, which should solve all problems; the minority stance is a bit subtler than that … It is not correct neither to present the idea of an exit as the only element of the minority toolbox, and that (in the case of Greece at least) debt restructuring is part of that toolbox seems to surprise some. Or then, when the fact is recognized, it is replied that that is excellent, but does not require an exit out of the eurozone. We come back to this point in an instant. A last point which I regret in this debate is the unfortunate bringing in of names of authors as J. Sapir or E. Todd (with ideas sometimes very debatable from a left point of view) in a way which may some lead to believe that they are brothers in arms of the ‘minority’. Quod non. (Let me point out that when I speak here of a ‘minority’ and a ‘majority’, it is only for the purpose of the present note.).

But the main thing is that important points of the debate which were ‘abstract’ in 2014, have got a practical answer in 2015, through the developments in Greece. It was probably not manifestly naïve in 2014 to propose that Greece take unilateral measures of debt restructuring and anti-austerity without considering the question of membership of the eurozone. After these developments, everyone knows for sure what happens to a euroland which only starts debating on debt and austerity. This should also shine a different light on the strategy of ‘disobedience’ to the treaties of the EU, proposed by the authors of Que faire de l’Europe? and quite generally within left europeanist circles, as the ‘correct’ orderword. We now know that a party or a government in the eurozone which is serious about disobeying the European rules should be as serious about leaving the eurozone. This implies exit is presented and explained as a possible step in the political programme, that such a step is studied and prepared, that enquiry missions are sent to Iceland, Argentina …, etc. The recent book, Euro, Plan B – Sortir de la crise en Grèce, en France et en Europe, Ed. du Croquant, August 2016, by Lapavitsas, Flassbeck, Durand, Ethiévant and Lordon, foreword by Cukier and Kouvelakis, is a concrete step in such a preparation process.

The remarkable fact now is that Stiglitz’ book is also a contribution to such a process. After having presented the reforms which he considers essential (and ’eminently doable’) to make the euro ‘work’, but doubting that they will be implemented, he switches to an exit scenario, preferentially amicable, but even in the other case ‘still less onerous than the current depression’. For the practical problem of quickly introducing new currency, for instance, he suggests electronic money would mainly solve the problem (given also poor people get an account and a banking card). Maybe a useful idea in itself, but above all the proof that this moderate neo-keynesian is serious about his diagnosis that European leaders are not likely to be impressed by his recommandations to save the euro, and that ‘muddling on’ is the most probable scenario. In contrast with Que faire de l’Europe?, Stiglitz does not sketch a dantesque scene of infernal devaluations after an exit, in his opinion even a non-amicable divorce would offer more hope for a country like Greece than muddling on. If such thinking had been more common in Greece last summer instead of the left europeanism catastrophic visions of permanent devaluation after an exit, wouldn’t that have helped the Greek left inside and outside Syriza to oppose a third Meomorandum?

Urgent measures versus long term wishes

To conclude, I don’t think the main difference between Stiglitz and the ‘left Europeanists’ is, as far as their position on an euro-exit is concerned, one of radicalism, realism in assessing the consequences or the result of differences in political outlook. I think they consider different scenarios and different time scales. Stiglitz sees an enormous problem which takes more victims every day and risks to explode in a non too far off future. He thinks about scenarios which a country like Greece could follow in order to improve the situation (or better: to escape a daily worsening of it). Left europeanists, from their side, have a different perspective: how to transform the eurozone (or the whole EU) from a neoliberal prison into a progressive hopeful project for the peoples of Europe? Their perspective is a scenario (at a non predictible point in time) in which several countries have simultaneously their ‘Syriza’, and take that opportunity to change Europe in a progressive sense. A certain lightfootedness of the approach transpires when Que faire de l’Europe? assumes an argument which is more commonly heard in social democratic circles: Who says the European treaties are set in stone? Didn’t the European Commission close its eyes when States gave massive financial support to their banks? Didn’t the ECB buy sovereign bonds in order to prevent the explosion of the eurozone? Certainly, they did, dear friends, but call me the first time they break their rules in order to service the people.

Whereas the Stiglitz/’minority’ approach offers concrete answers to urgent problems which very probably pose themselves in a not too distant future somewhere in Europe (Greece? Portugal? Italy? Spain?), the other approach seems not to feel any sense of urgency as it depends critically on a rather improbable conjunction of events in a non further defined future, and offers little perspective for the unhappy country which would arrive prematurely at the rendez-vous. Or it should be that the positive developments in a country which enters the first scenario trigger the second one … Rather than the ‘underseller’, it would then become the pacesetter.