Jul 26, 2024

The Palestinian people were forcibly expelled from their homeland by Zionist armed militias in 1948, in an event which remains in their collective historical memory as the Nakba, or the Catastrophe. The Zionist project had always envisaged such a development, and all genuine revolutionary Communists had consistently been opposed to the Zionist ideology. Why then did Stalin abandon the position of one state for the two peoples, Palestinian and Jewish, and come out in support of partition in 1947, together with the subsequent setting up of a separate Jewish state?

Lenin opposed the reactionary ideology of Zionism. He understood that the Zionist project could only be achieved at the expense of the Palestinian people. At the Second Congress of the Communist International in 1920, the Theses on the National and Colonial Questions, drafted by Lenin, stated:

“The Zionists’ Palestine affair can be characterised as a gross example of the deception of the working classes of that oppressed nation by Entente imperialism and the bourgeoisie of the country in question pooling their efforts (in the same way that Zionism in general actually delivers the Arab working population of Palestine, where Jewish workers only form a minority, to exploitation by England, under the cloak of the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine).”

The question has to be asked, therefore, as to why Stalin adopted a position which was diametrically opposed to that of Lenin? Stalin actually played a key role in getting the infamous 1947 UN resolution that partitioned Palestine adopted with the required two-thirds majority of the UN Assembly.

Present-day supporters of Stalin prefer that we bury and forget these facts. They would like to uphold the myth that they, the Stalinists, have always opposed Zionism. Others have attempted to find justifications for Stalin’s betrayal of those basic principles that were established during the first four congresses of the Communist International.

Unfortunately for them, historical facts are difficult to erase, and the truth is concrete. No amount of contorted arguments can in any way justify what Stalin did. Let us look at how and why this complete abandonment of Lenin’s position came about, and also how this key event impacted Communist Parties, particularly in the Middle East.

In the years building up to this, the official Soviet position had remained that of opposition to the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. The Soviet government continued to put forward the idea of one state for two peoples. And the Communist Parties in the Middle East, and around the world, publicly campaigned against the Zionist project.

That said, on more than one occasion high-ranking Soviet diplomats during and immediately after the Second World War were involved in encounters with leading Zionist figures in which they expressed support, or at least sympathy, for the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. It was evident that behind the scenes the policy of the Soviet government was changing.

Records show that as early as 1940, shortly after the 1939 Hitler-Stalin pact in which Poland was divided between Germany and the Soviet Union, something was moving on this front. Because there was a large Jewish population in Poland, a significant number of Polish Jews were now under Soviet rule. Zionist leaders saw in this an opportunity for increased migration of Jews to Palestine.

In his Moscow’s Surprise: The Soviet-Israeli Alliance of 1947-1949, using archive material from the Soviet Union, Laurent Rucker provides interesting details about contact between Soviet diplomats and important figures within the Zionist leadership. The source for details of this encounter comes from ‘Sovetsko-Izrail’skie otnoshenia. Sbornik Dokumentov 1941-1953 (SIO) (Moskva: Mezhdunarodnye Otnoshenia, 2000), vol. 1, pp. 15-17’, official documents on Soviet-Israeli relations.

A meeting that took place in January 1941 between Chaim Weizmann, the president of the World Zionist Organisation, and Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador to the UK, was very revealing. According to Rucker:

“…Weizmann brought up the future of Palestine. Maisky stated that there would have to be an exchange of populations in Palestine in order to settle Jews from Europe. Weizmann replied that if half a million Arabs could be transferred, two million Jews could be put in their place. Maisky did not appear to be shocked by this idea.” [My emphasis]

Rucker continues:

“The catastrophic change in the position of the Soviet Union following the German invasion of the USSR just five months later offered the Zionists an opportunity to expand on their early contacts. They began to pursue more forcefully two major goals: (1) to reach an agreement with Moscow that would allow Polish Jews in the Soviet Union to emigrate to Palestine, and (2) to convince the anti-Zionist Bolshevik leaders that the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine would not be contrary to their interests.”

This was followed by a meeting in London in October 1941, between Maisky and David Ben-Gurion – then-president of the Jewish Agency, and later founder of the Israel Defence Force and Israel’s first prime minister. And in 1943, Maisky again met with Weizmann, reassuring him that the Soviet government understood the aims of the Zionists and would “certainly stand by them” (Rucker). Maisky even visited Palestine and met with Ben-Gurion, and he seems to have been very impressed with what the Zionists were building there.

As we can see, Moscow was already considering the possibility of supporting the setting up of a Jewish state in Palestine, which would necessarily include the removal of half a million Palestinians from their homeland, although this was not made public. The official position remained that of opposition to a solely Jewish state and support for a single, bi-national state.

In 1943, Stalin had dissolved the Communist International, having no use for it, as he had long before abandoned the perspective of world revolution. It was also a gesture to please his then-allies in the West, Churchill and Roosevelt, amidst the Second World War.

The Stalin regime behaved in the same manner over the question of Palestine, with Soviet foreign policy being conducted entirely behind the backs of national Communist Parties. The encounters between Soviet diplomats and key leading figures in the Zionist movement were thus completely unknown to both the ranks and the leaderships of these parties.

The 1947 Gromyko Speech at the UN

Palestine was then under British mandate. But Britain was declining as a power, and faced the loss of its empire. It could no longer sustain its presence in Palestine, and was actually seen as an enemy by the local Zionists, whose aim of setting up a Jewish state was in conflict with the interests of British imperialism at the time.

Britain, at various times, made noises that could have been interpreted as promising Palestine both to the Arabs and the Jews. This was in line with their tested method of ‘divide and rule’. British imperialism in fact opposed the setting up of a separate Jewish state. This was not out of any love for the Palestinians. Its main concern was to establish friendly relations with the oil-rich Arab regimes in the region. But by the end of the Second World War, the power to decide the destiny of Palestine lay with Washington – aided by Moscow – and not London.

That explains why, in February 1947, the UK government decided to relinquish its mandate, and hand over the task of establishing the future status of the territory to the newly established United Nations.

It is in this context that Andrei Gromyko, the representative of the Soviet Union at the United Nations, delivered an important speech to the UN General Assembly on 14 May 1947. Its content came as a shock to millions of communists who adhered to the official Communist Parties all over the world. However, it was particularly shocking to the ranks of these parties in the Arab world.

It was a speech about the setting up of a special UN committee on Palestine. Gromyko spoke at length, highlighting the plight facing large numbers of displaced Jews in Europe at the end of the Second World War. He was clearly preparing the ground for what would come later that year.

In the speech, Gromyko stated:

“The fact that no western European State has been able to ensure the defence of the elementary rights of the Jewish people, and to safeguard it against the violence of the fascist executioners, explains the aspirations of the Jews to establish their own State. It would be unjust not to take this into consideration and to deny the right of the Jewish people to realise this aspiration. It would be unjustifiable to deny this right to the Jewish people, particularly in view of all it has undergone during the Second World War.” [My emphasis]

He then went on to list four different possible solutions to the question:

“1. The establishment of a single Arab-Jewish State, with equal rights for Arabs and Jews;

2. The partition of Palestine into two independent States, one Arab and one Jewish;

3. The establishment of an Arab State in Palestine, without due regard for the rights of the Jewish population;

4. The establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine, without due regard for the rights of the Arab population.” [My emphasis]

In his concluding remarks, he stated that “an independent, dual, democratic, homogeneous Arab-Jewish State” would be the only way of guaranteeing the rights of both the Jewish and the Palestinian populations. However, he then added that should this prove impossible to apply, “the partition of Palestine into two independent autonomous States, one Jewish and one Arab” would have to be considered.

Subsequent history shows that the speech was, in fact, preparing the ground for the Soviet Union to give full backing to the Zionist project of expelling hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homeland and the setting up of Israel – in effect, carrying out what Maisky had discussed with leading Zionists just a few years earlier. But most importantly, the words match the hard facts. Between 1947 and 1949, the Soviet Union provided full backing to the Zionists, politically and militarily, and even by facilitating greater migration of Jews from eastern Europe to Israel.

A member of the Soviet UN delegation, S. Tsarapkin, delivered a speech at the UN on 13 October 1947, in which he went further than Gromyko, publicly stating the Soviet Union’s support for the partition of Palestine. As Rucker states, “The USSR was becoming an ardent supporter of the Zionist cause.”

The USSR votes for the creation of Israel

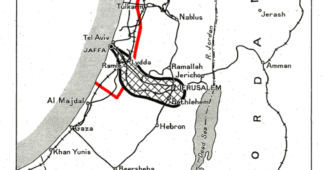

The following month, on 29 November 1947, the USSR voted in favour of the partition of Palestine. Resolution 181 was passed in the UN General Assembly with 33 votes in favour, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. The Zionists could not have asked for more from Stalin!

It must be remembered here that for such a UN Resolution to be legally binding, a two-thirds majority was required in the Assembly. Stalin controlled Byelorussia, Ukraine, Poland, and Czechoslovakia, as well as the USSR – all of which were members of the UN with voting rights at the time, and all of which voted for partition. Had these five countries voted against partition, the vote would have been 28 in favour, 18 against and 10 abstentions. The resolution would have thus fallen. There is no escaping this fact.

What happened subsequently is well known. The Arab countries refused to recognise the UN resolution; the Zionist armed forces filled the vacuum by launching a campaign of terror against the Palestinians, aimed at pushing them out and establishing Israel, and war broke out with the nascent Jewish state. In the process, 700,000 Palestinians were ‘ethnically cleansed’, to use a sanitised term for the brutal and bloody expulsion of a whole people from their homeland. The present genocidal onslaught of Israel against Gaza has its roots in those tragic events.

The Soviet Union not only assisted the Zionists by voting for the UN resolution. It also provided arms, albeit indirectly via one of its satellites. In 1948, Stalin allowed Czechoslovakia to ship heavy weapons to the newly formed Israeli army. From the end of 1947 through to 1948, the Zionists and the Jewish Agency in Palestine bought $22 million worth of weapons from Czechoslovakia. This would be the equivalent of one quarter of a billion dollars in today’s money. At the same time, the USSR blocked the Czechoslovak government from going ahead with planned arms sales to the Arabs.

Many years later, in 1968, referring to the help provided by the USSR and Czechoslovakia, Ben-Gurion admitted that, “They saved the country; I have no doubt of that. The Czech arms deal was the greatest help we then had, it saved us and without it I very much doubt if we could have survived the first month.” (Uri Bialer, Between East and West: Israel’s Foreign Policy Orientation, 1948-1956, Cambridge University Press, 1990).

The Soviet Union also helped by facilitating the migration of Jews from Eastern Europe prior to 1948, with significant numbers coming from Poland, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia. The bonds forged with the Zionists were so strong that the USSR was the first country to legally recognise the state of Israel after Ben-Gurion proclaimed the new state in May 1948. In a telegram sent on 17 May 1948 to Shertok, the Foreign Minister of the Provisional Government of Israel, Molotov (Soviet foreign affairs minister, and Stalin’s closest ally) wrote:

“This is to inform you that the Government of the USSR has decided to extend official recognition to the State of Israel and its Provisional Government. The Soviet Government believes that the creation by the Jewish people of its sovereign state will serve the cause of strengthening peace and security in Palestine and the Middle East and expresses confidence that friendly relations between the USSR and the State of Israel will develop successfully.” [My emphasis]

“Peace and security” were the last things guaranteed by the creation of Israel. But Stalin’s cynicism went even further in December 1948 when Resolution 194-III was presented to the UN. The resolution posed the right of Palestinian refugees to either return to their homes or to receive compensation for loss or damage to their property. The Soviet Union and its East European satellites all voted against, while the US and British imperialists voted in favour!

Of course, nothing concrete was ever done to implement the resolution by any of the powers that voted for it. When Israel was finally allowed to become a member of the UN in 1949, one of the conditions was that it must agree to implement Resolution 194. One of Israel’s representatives verbally accepted, after which they continued to ignore the resolution, arguing that people who had fled and abandoned their properties had no right to compensation, and implemented in 1950 the infamous Absentees’ Property Law, in direct violation of the UN resolution, to expropriate the homes of all displaced Palestinians. The Soviet Union was so tied to its pro-Zionist position that it refused to even go through the motions of support for the rights of Palestinian refugees who had been brutally expelled from their homeland.

Why Stalin supported partition

What we have listed above are the facts. But what we have to ask ourselves is: why did Stalin adopt such a policy? We can only begin to answer this question if we understand that Stalin was not guided by the interests of the world working class. His decisions were not determined by a revolutionary perspective for the overthrow of the capitalist system. His actions were not determined by what was best for promoting socialist revolution globally. His interests were much narrower than that.

His thinking was determined by the national interests of the bureaucracy that had usurped power from the working class in the Soviet Union, and represented the backbone of Stalin’s regime. This process of degeneration of the revolution – due to its isolation in a single, underdeveloped country – was very well outlined by Trotsky in his classic text, The Revolution Betrayed.

This explains how the Stalinist-led Soviet Union could align with both US imperialism and the Zionists in 1947. The US, for its part, had an interest in allowing the emergence of a Jewish state of Israel, as it saw this as a way of pushing out the British from the Middle East, replacing them as the dominant power in this important, oil-rich region. Stalin also saw the Jews in Palestine as a useful lever to weaken British imperialism, while hoping to establish a point of support for the USSR in the Mediterranean.

Stalin is presented by his supporters as a great strategist, and those in the communist movement who try to justify his policy in Palestine at the time, do so by trying to show that there was some kind of clever plan behind all this. But the truth is that because he had no perspective of a socialist transformation of the Middle East, the best he could come up with was the prospect of a Soviet-friendly Jewish state in Israel, i.e. a capitalist Israel with friendly relations with the USSR.

There was nothing clever in all this. In an essay published in Diplomatic History in 1989, titled, Intelligence, Espionage, and Cold War Origins, John Lewis Gaddis explains that:

“What is often forgotten about Stalin is that he wanted, in his way, to remain ‘friends’ with the Americans and the British: his objective was to ensure the security of his regime and the state he governed, not to bring about the long-awaited international proletarian revolution; he hoped to do this by means short of war, and preferably with Western cooperation.” [My emphasis]

Gaddis is considered an expert in Cold War history and writes from the point of view of the interests of US imperialism. His appraisal of Stalin confirms our understanding of what moved the man. Ever since he adopted the theory of ‘socialism in one country’ shortly after the death of Lenin in 1924, his thinking represented the interests of the conservative bureaucracy and not that of the world working class. The bureaucracy was made up of many non-communist elements, many people who had joined the party as a means of promoting their own careers. They had acquired material privileges in the process and desired a quiet life in which they could enjoy these privileges. The last thing they were concerned about was world revolution.

The theory of ‘socialism in one country’ also resonated with a growing nationalist outlook of the great-Russian bureaucracy. They viewed the Soviet Union and its planned economy not as an outpost of the world proletarian revolution, but as the means of maintaining their own material interests as a caste. They identified the ‘national interests’ of Russia in narrow nationalist terms with their own interests, rather than with the struggle for a new worldwide socialist society, which the Bolsheviks under Lenin had aspired to. And the policy of the Soviet Union in the Middle East was determined by these interests.

Initially, Stalin believed an agreement could be reached and maintained between the Great Powers, whereby each would have its sphere of influence, and each would respect the interests of the others. In this context, he believed that Israel could become an ally of the Soviet Union. So much for an ‘intelligent’ policy on the part of Stalin! Within a very short time, it became abundantly clear that Israel was becoming a key ally of US imperialism in the region.

Many of the founders of Israel dressed themselves in ‘socialist’ clothing, Ben-Gurion being a prime example. In the early days of the creation of Israel, the state, and even the Histadrut trade union federation, which was linked to the state, played a key role in developing its economy, nurturing the consolidation of an Israeli capitalist class, which was initially weak. All this was used to spread the myth that Israel was some kind of ‘socialist experiment’. Among the Jews of Eastern Europe, there had been a strong socialist tradition and many of the Jewish migrants arriving in Israel came from this background. The kibbutzim – settlements established around collective farms – were presented as examples of socialist organisation. At their peak, they represented a significant percentage of agricultural production and even industrial production with hundreds of kibbutz factories.

The idea that Israel could be a ‘socialist experiment’ ignores the fact that the kibbutzim were often armed outposts of Israel, and played an important role in colonising the land that had previously belonged to Palestinians. As some have described it, it was a “socialism only for the Jews, not the Arabs”.

One cannot build socialism in this way. Socialism either comes from a united movement of the whole of the working class – in this case, both Jewish and Palestinian – or it will turn out to merely cloak and assist in the oppression of one section of society by another, to the ultimate benefit of the capitalist class. What was being built was capitalism, and precisely because of its isolation and oppressive nature, it soon became an entrenched outpost of imperialism in the Middle East. That also explains why the most powerful imperialist country on the planet had no problem with this kind of ‘socialism’.

The damaging effects on the Communist Parties in the Middle East

As could be expected, Stalin’s decision to support the partition of Palestine and the creation of Israel had a devastating effect on the Communist Parties in the region. As Mohammed Shafi Agwani, an Indian professor, explained in his book, Communism in the Arab East (London, 1969):

“The precipitous decision of the Soviet Union to back up partition, therefore, had a stunning effect on the Palestinian Communists… the drastic change in Soviet attitude – from denouncing Zionism as an ‘imperialist conspiracy’ to conceding its basic claim – gave a severe jolt not only to the Palestinian Communists but to all the Arabs. (…)

“Whatever the reason for the Soviet somersault, it was no easy task even for the most ingenious among the Communists to sustain it ideologically. But once the Soviet Union had stated its position in unmistakable terms, the Communists had no option but to make adjustments.”

The Stalinist bureaucratic degeneration of the Soviet Union – a process that had started in the mid to late 1920s, and which was consolidated in the 1930s with the Stalinist Purges – also led to the transformation of the Communist International itself from being a genuine organisation of world revolution into one totally controlled by the Soviet government. The latter dictated its line, with all its unexplained zig-zags, determined by the momentary needs of the bureaucracy in the USSR.

This meant all the original internal democracy of the Communist International of the period of the first four congresses was crushed. Dissent was no longer tolerated. A line was laid down, and it had to simply be obeyed and applied. Thus, once the Soviet Union had voted for the partition of Palestine, the Communist Parties in the region had to defend the new position of the USSR. But as Agwami explained:

“…the Arab Communists had an immensely difficult time explaining to their followers the reasons underlying the Soviet posture. (…) The Communists emerged from this final act of the Palestinian tragedy severely bruised and battered, morally as well as politically. There was acute confusion in the Communist ranks.”

It led to a tragic situation, in which Jewish and Palestinian Communists ended up on opposite sides of the war that followed the formation of Israel, with the former actually supporting Israel’s “defensive war”. In Iraq, the local Communists, loyally supporting Stalin’s position, actually organised demonstrations in support of the UN partition resolution, and called for cooperation with the “democratic forces” in Israel! Those Arab Communists, on the other hand, who had the courage to oppose Stalin’s line, joined the war against Israel. Thus, Communists ended up on opposite sides of the barricades to one another, in a real armed conflict.

In early 1944, shortly after the official dissolution of the Communist International in 1943, the Palestinian Communist Party split along ethnic lines, with the Palestinians breaking away to form the Arab ‘League for National Liberation’ (LNL).

The LNL opposed the partition of Palestine but was in favour of granting Palestinian citizenship to Jews who had emigrated to the country. Emil Tuma of the LNL wrote to Moscow shortly after Gromyko had made his infamous speech in May 1947, criticising the position of possibly supporting partition

He explained that:

“…the speech aroused suspicion and distrust in the Arab world among the wide Arab masses, and Arab reactionaries managed to throw doubt on the attitude of the Soviet Union towards the Palestine problem, which is regarded as an integral part of the Arab problem in the Middle East. (…)

“Gromyko’s statement has aroused great speculation among communists. It has been badly received by the Arab masses and a clarification would give hope not only to communists but to all Arab people in the Middle East. The revolutionary potential in the Arab countries cannot be ignored in the present international situation.”

Tuma also criticised Gromyko for having, “…ignored completely the Arab people in Palestine, their aspirations, their anti-imperialist national movement and their traditional associations and bonds with the Arab people in the Middle East.”

Tuma’s main criticism of Gromyko’s speech, however, was directed against his open support for the Zionist cause. He explained that:

“We have always fought against the Zionist conception and have viewed Zionism as an imperialist venture directed by British imperialism in order to create a Trojan horse in the Middle East. Consequently we have always discredited the historical claims of Zionism as reactionary and did not accept the historical roots of the Jews as realistic. (…)

“Comrade Gromyko by his statement has strengthened Zionist ideology and the Zionist grip over the Jewish masses. Such strengthening will help imperialism to continue to use the Jewish masses as instruments in its opposition to the liberation movements in the Arab Middle East.” (Moscow’s Surprise: The Soviet-Israeli Alliance of 1947-1949)

Once partition was carried out, the LNL campaigned for a Palestinian state to be set up in accordance with the partition resolution passed by the UN General Assembly in November 1947.

This was never to be achieved, however, as the outcome of the war in 1949 meant that what is known today as the West Bank was annexed to Jordan, while Gaza was placed under Egyptian administration. These territories would later be occupied by Israel in 1967, and have remained so ever since. We see here how even Gromyko’s “two independent States” in reality meant a powerful Jewish state, and the denial of any kind of statehood for the Palestinians. It was, in fact, his fourth option – one Jewish state with no regard for the rights of the Palestinians – that became the reality. It was a betrayal of the Palestinian people in every sense of the word.

We must state it clearly here: Stalin’s support for the creation of Israel created a disastrous situation for the Communists in Palestine and for the Communist Parties in the whole of the Arab world. It proved to be a huge setback for the ideas of Communism throughout the region.

And it was not just an ideological setback. There were actually physical attacks on Communist offices in places like Aleppo and Damascus, and Soviet diplomatic missions were also targeted. In Lebanon and Syria, the authorities exploited the general mood to legally ban the Communist organisations.

All this weakened the Communist Parties, not just in terms of their political and moral authority, but also in terms of their actual strength on the ground. Between August 1947 and June 1949, the membership of the Lebanese Communist Party fell from 12,000 to 3,500, while in Syria membership declined from 8,400 members to 4,500. Thus, their forces were reduced by between two-thirds and one half.

In Iraq, the first half of 1948 witnessed a revolutionary wave, led by the Iraqi Communist Party. The declaration of the state of Israel and its recognition by the USSR in May was exploited by the authorities to declare martial law, crush the movement, to politically isolate the Iraqi Communist Party, the leaders of which were arrested, condemned to death, and executed in February 1949. This is the tragic balance sheet of Stalin’s “clever strategy”.

The impact of Stalin’s policy lasted for years in the region. But it also affected the Communist Parties in many other countries. Everywhere, the Communists had had a policy of opposition to the partition of Palestine, but when the USSR voted for partition at the end of 1947, confusion was sowed among their ranks.

Unprincipled shift of the Communist Parties in the West

Describing the effect it had in the United States, Dorothy Zellner – the daughter of parents who “were secular, non-Zionist Jewish immigrants and lifelong followers of the Soviet Union” – wrote in Jewish Currents in 2021: “The US Communist left was dumbfounded.” She describes how generalised confusion was stirred up among US Communists at the time.

To take another case, the Italian Communist Party (PCI) came out openly in support of the UN partition of Palestine. Ironically, the Christian Democratic government headed by Alcide de Gasperi at that time maintained an ambiguous stance on whether to officially recognise the state of Israel, not wishing to damage relations with the Arab regimes. As in Britain, the Italian ruling class was mainly concerned with the supply of oil, which was essential to its own economic interests after the Second World War. It was also trying a one last ditch attempt to keep the colonies it had before the Second World War, and to this end, hoped for Arab support in the United Nations. For this reason, the Italian government did not officially recognise the state of Israel until February 1949.

The PCI, on the other hand, gave full support to Israel, completely in line with the position adopted by the Soviet Union. A study of its organ, L’Unità in the years 1946-48 is very revealing. It presented the Zionists as fighting an anti-imperialist struggle for national independence against British imperialism. In one issue, on 29 May 1948, an unsigned statement – although most likely drafted by the then-editor of the paper, Pietro Ingrao – refers to “The heroic resistance of the Jews” (“L’eroica resistenza degli ebrei”), when what was actually taking place was ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians by Zionist terror on a grand scale.

In an editorial in L’Unità, on 29 May 1948, Pietro Ingrao lambasted the Italian government for not recognising the newly formed state of Israel. Only two days earlier, on 27 May, an official statement of the party leadership was published in which they called for the immediate recognition of Israel as “a manifestation of international justice and a sign of solidarity with a people who are heroically defending their existence, threatened yesterday by the Hitlerites, and today by the leaders of Western democracies”.

In Britain prior to 1947, the Communist Party had stood for one single state in Palestine, with equal rights for the different ethnic groups, living side by side, as part of an Arab federation. But once the Soviet government came out in support of partition, the party switched accordingly.

In 1948, the organ of the Communist Party in Britain, the Daily Worker, came out in support of the creation of a Jewish state. It called for the implementation of the UN resolution on the partition of Palestine. In May 1948, it saw in the establishment of Israel, “a big step toward fulfilment of self-determination of the peoples of Palestine” and “a great sign of the times”. (Daily Worker, 15 May 1948) And they declared that the armed Jewish militias in Palestine fighting against British forces as an anti-imperialist struggle, stating that ‘the days of imperialism are numbered’. (Daily Worker, 22 May 1948)

When Israel was finally created, they said that it should be championed by all “progressive forces”. And when the Arab countries attacked Israel as it was being established, the Daily Worker denounced this as imperialist aggression! William Gallacher, Communist Party MP for West Fife, called for the recognition of Israel and recommended the immediate end to military aid to the Arabs.

All this changed once the position of the Soviet Union again changed. A few years later, we find the PCI leadership describing Israel as a bridgehead of western imperialism in the Arab world, and the British Communist Party suddenly discovered that Israel had always been a tool of US imperialism.

This was all in line with Soviet policy, which in the early 1950s went through another 180-degree turn, now becoming anti-Zionist. And in February 1953, diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and Israel were broken off, after the outbreak of the infamous ‘Doctors’ Plot’, an antisemitic campaign that was launched in the Soviet Union, when a group of mostly Jewish doctors were accused of conspiring to assassinate Soviet leaders.

As we can see, Stalin’s ‘principles’ were extremely flexible in such matters! The ‘principles’ of the leaders of the Communist Parties around the world were equally flexible, merely amounting to “say and do what Stalin tells you to do”, although it could prove to be difficult to act swiftly without prior warning. If Stalin supported the creation of Israel, they merely jumped into line. And when he turned completely in the opposite direction, they once more jumped accordingly.

Return to Lenin!

These are not the methods of Lenin, they are not the methods of the Communist International in its first four congresses, when Trotsky described it as “a school of revolutionary strategy”. They are the methods of a bureaucracy that had given up on the perspective of world revolution and only sought its own narrow national interests. But in so doing, they weakened the Communist Parties for decades to come, and stained the banner of Communism in the eyes of the working masses in this region and throughout the world.

This, in part, explains how radical Arab nationalism was able to dominate the revolutionary movements that exploded after the Second World War in many countries in the region. It also partly explains the rise of phenomena such as ‘Ba’ath Socialism’, and so on.

As the Arab masses became radicalised through their struggles against imperialism, this was reflected in a number of countries, including Iraq, Egypt and Syria, in, now active, now passive mass support for revolutionary anti-imperialist measures taken by a layer of the radical intelligentsia, and even a layer of army officers, that expressed these ‘left’ nationalist ideas.

The idea of centralised economic planning, of state ownership of the means of production, exerted an attraction on some of the more radical elements among these petty-bourgeois layers. They saw how the planned economy in the Soviet Union, despite its bureaucratic deformations, had allowed it to develop into a modern industrialised power. We should add that they were also attracted by the fact that a privileged bureaucracy was in power in the USSR.

Ironically, however, while all this was unfolding, in many countries – such as Egypt and Syria for example – the local Communists were heavily repressed.

Had the Soviet Union and the Communist Parties in the Middle East maintained a firm stance in defence of the idea of one state for two peoples, had they not betrayed the cause of the Palestinian people, these parties could have played a key role in the region, taking up the leadership of the working masses and the youth.

This tragic episode in history demonstrates that the ideas a party defends, the way a party acts, and the positions it adopts on key questions, can either strengthen or weaken it. It can literally mean the difference between building or destroying the party’s forces. Stalin’s policy in the period 1947-49 in the Middle East massively weakened the Communist Parties, and therefore prepared the ground for defeats of revolutionary movements and the rise of reaction.

In that period of history, however, there were other Communists of a different type – we would say true Communists – who, in spite of the brutal Stalinist repression, continued to adhere to the methods and ideas of Lenin. These were the followers of Leon Trotsky. In Britain they were organised in the Revolutionary Communist Party. In their journal, Socialist Appeal, they took a principled stand. In A clean banner: British Trotskyists opposed 1948 partition of Palestine, we published two articles from the Socialist Appeal in November and December 1947, just after the UN adopted the resolution on partition. The articles warned against the consequences of partition, and concluded:

“Partition of Palestine is reactionary from every aspect – neither the Jews nor the Arab masses have anything to gain from it. It pits Jew against Arab, diverts the struggle against imperialism into a struggle between those whose common interest it is to struggle against imperialism. It plays into the hands of the Arab landowners and capitalists by diverting the attention of the Arab peasants and workers from their exploiters. The only solution to the problem of Palestine and the Middle East is the scrapping of the imperialist plans of partition, the immediate and complete withdrawal of all troops from Palestine and the Middle East. There can be no real independence or safety for the Jews or Arabs in partitioned Palestine.”

Those comrades would be proven right many times over in the subsequent 76 years. Since 1948, we have borne witness to a history of bloody conflict after bloody conflict. The Palestinians have been denied a homeland ever since, while Israel has proved to be anything but a safe haven for Jews.

We stand today on the shoulders of our RCP comrades back in 1947-48 in advocating a homeland for both people, which could only be achieved in the form of a socialist state across the whole of historical Palestine, within a Socialist Federation of the Middle East, in which both Jews and Palestinians could live in peace on the basis of the socialist development of the economy.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.