By Tim Judah

31 March 2021

For Southeast Europe it is the invisible catastrophe that is slowly engulfing the region. From the shores of the Adriatic to the Black Sea, populations are shrinking and aging and ever fewer children are being born. For decades young and able people have been emigrating, and the region has no immigration to make up for it. A decade ago, unemployment was one of the biggest problems of the region. Now labor shortages are increasingly the issue. Today pensions are small, but in the future, with fewer people of working-age paying contributions, they will be smaller.

Something surprising could happen but, if it doesn’t, the future looks bleak. Governments are fully aware of these problems but mostly don’t know what to do about them, don’t have the money to do anything or prefer to kick the can down the road. There are, after all, no votes to be won by instituting reforms which might not yield results until years after you have left office.

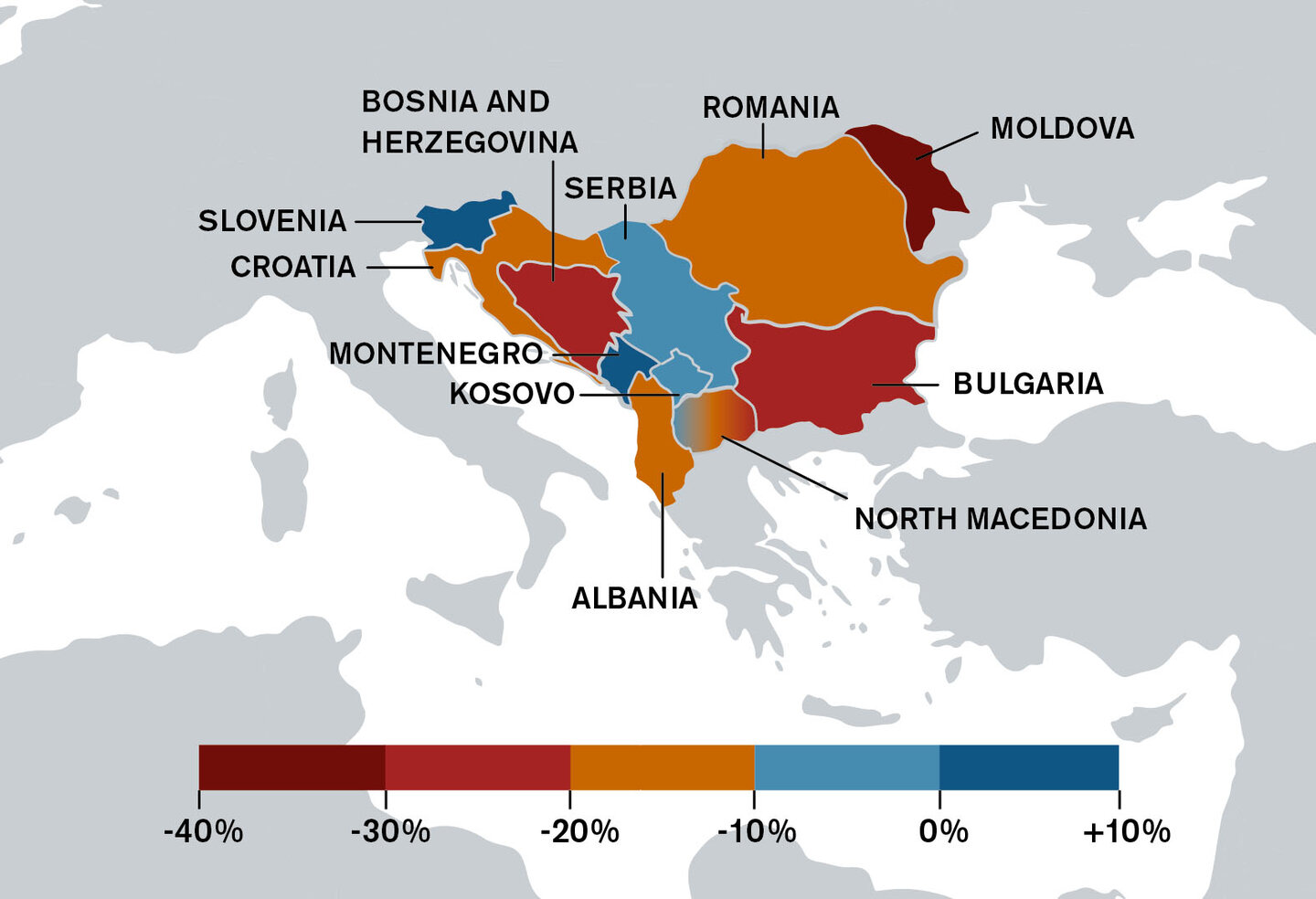

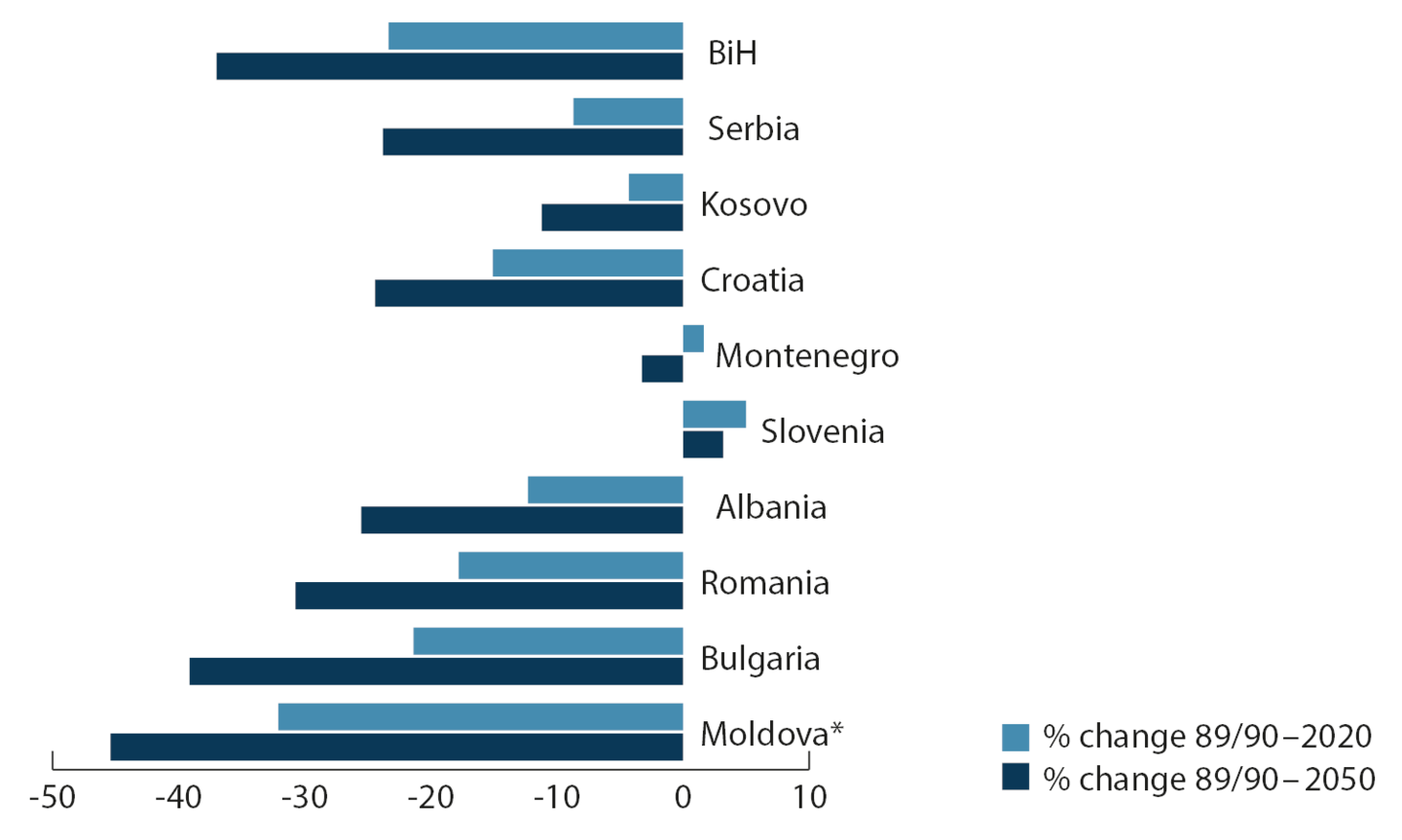

Figures across the region are unreliable but the trends are clear, especially if looked at over decades rather than years. Since the collapse of Yugoslavia, Bosnia and Herzegovina has lost 24% of its population, Serbia 9% and Croatia 15%. Since 1990 Albania has lost 12%, Romania 18%, Bulgaria 21% and Moldova 32%. If you fast forward to 2050, on current projections Moldova will have lost more than 45% of its population since 1990, Bulgaria 39%, Bosnia 37%, Serbia 24% and so on.

It is widely believed that the world is overpopulated, so if a country’s population shrinks that is better for the environment and there will be less pressure on resources, and so on. That might be true except for a few other key determinants. The trends show that not only are populations shrinking but that they are also becoming older and fertility rates are dropping.

How serious is the baby bust?

The fertility rate measures how many children the average woman has. For any given population to replace itself that number needs to be 2.1. There is no country in Europe, except perhaps Kosovo, which surpasses that figure and for decades it has been dropping across the world. In the EU, the average is 1.53. Its highest rate is in France at 1.83 and its lowest is in Malta at 1.23.

In Southeast Europe, fertility rates vary considerably. Bosnia’s is 1.2, which is one of the lowest on the planet, Montenegro’s is 1.7, and Kosovo’s probably hovers somewhere around 2.0, but no one knows for sure. It has the youngest population in Europe but its statistical agency, which has struggled to give reliable data over the last two decades, has published several wildly differing figures in recent years. Their latest is the extraordinarily high 2.3.

As everywhere else in the world births have fallen as a consequence of urbanization, the education of women and better health. As a result of the latter people live longer lives. In Southeast Europe too, people live far longer than ever before, though no country except for Slovenia has a life expectancy higher than the EU average of 81.3.

What does this mean for the region? It means that, quite apart from the factor of emigration, if more people die than are born, then populations are shrinking as well as aging. When you add emigration into the mix of course they shrink and age even faster.

Serbia is one of the older countries of the region and it has seen more coffins than cribs for decades. In the ten years prior to 2019, an average of 36,460 more people died annually than were born. Last year the number of deaths was higher because of COVID-19, so 53,261 more died than were born. Elsewhere in the region, this number varies considerably, but the trend is everywhere the same. Albanians still have more babies than funerals, but only just. In 2020 that number was a mere 470, although it would have been greater without the extra deaths caused by COVID-19.

Brain drain: a trickle or a torrent?

Unlike births and deaths, migration numbers are notoriously hard to pin down. One reason is that, more often than not, those who leave Southeast Europe stay registered as residents of their home country. Then, neighboring states often give citizenship to those outside their borders whom they claim as their own ethnicity. If that country is in the EU, then its passport makes living and working in the EU immeasurably easier. Thus, many Bosnian Croats move to Germany as Croatian citizens, most Moldovans working in the EU and the UK do so as Romanians and many Macedonians have acquired Bulgarian passports. How many Romanians in Germany are actually Moldovans? It is impossible to know.

Of all the countries in Southeast Europe, Moldova has seen the steepest drop in population, but it was only in 2019 that new software on the country’s borders began enabling the authorities to have an idea of how many people were in or out of the country at any one time. However even this could not give them a complete picture as the government does not have authority over all of Moldova’s frontiers because a large slice of the country is under the control of Russian-backed separatists.

By examining the data of countries to where people from Southeast Europe traditionally go, however, we can get a good idea of the sheer scale of recent emigration trends. In 2018, 228,000 nationals of the six non-EU western Balkan countries, or some 1.3% of their total combined population, moved legally to the EU28, then still including the UK. That included 62,000 from Albania, or 2.2% of its population. Yet more of course have left for countries outside Europe and by definition we do not know how many live abroad illegally.

Drill further into what data there is of legal migration in certain countries and the numbers are stunning. According to the German statistical agency, in 2019 there were 748,225 Romanians living in the country, 414,890 Croats, 237,775 Serbs, 232,075 Kosovars and 203,625 Bosnians. In Italy, there were officially 421,591 Albanians, 1.14m Romanians and 118,516 Moldovans who were not registered as Romanians. What these totals don’t show us of course is how many have acquired the citizenship of the country to which they have emigrated.

We also don’t know how many return home every year, nor do we have data on circular migration. Typically, that covers women who take care of the elderly abroad, men who go away to work on short-term construction projects and those who go abroad to work in agriculture.

While some who have lived and worked abroad may return home when they retire, few of their children will. They will contribute to the economy and pension funds of Switzerland and elsewhere and, more to the point, as the fertility rates of all western countries are way below 2.1, their populations too would shrink without this immigration. Even with it, Germany’s population stagnated in 2020, but only because COVID-19 disrupted normal immigration patterns.

A big data problem

This year most countries in Europe will conduct a census. This will help us to understand how many people actually live in each country – or at least more or less. Bosnia however won’t hold one and Moldova won’t hold one until 2023. The country that needs it most though is North Macedonia but here, like in many other countries, its census due to start in April has been postponed due to the pandemic. Officially its population is 2.08m but that is nonsense according to Apostol Simovski, the head of its statistical agency. When political parties of the majority Macedonian population and minority Albanians tried to inflate their respective numbers at the last census in 2011 the entire operation collapsed. Now, thanks to its shrinking birth rate and high rates of unrecorded emigration, he reckons the total population could be as low as 1.5m.

Consider for a moment what it means if your population figure is wrong, let alone wildly so. It means that every other figure you need for planning a modern state from your fertility rate (how many schools and teachers will you need in the future?) to your GDP per capita is also wrong. North Macedonia is not the only country with a big data problem. According to several experts, 3.2m is a good estimate for the number of people who live in Bosnia, but in 2018 its Labor Force Survey, which is another way of measuring population, gave that number as 2.7m, a figure which is however disputed.

What is not disputed however is that Bosnians, like everyone else in Southeast Europe, are getting older. But what does this mean? According to a 2018 study, the share of people aged 65 and over in the Western Balkans may double to 34% by 2060. At the same time the population aged 20 to 64, which was 62% of the population in 2015, will have dropped to 49% by 2060. Specifically, the report foresees 45% of Bosnians as being aged 65 or more in 2060, 30% of Serbs and so on.

What the demographic future holds

Although these figures are alarming, predicting the future is a risky business. Projections are made by guessing what the future holds and, in the wake of COVID-19, it is clear to everyone that the shape of the future can change fast. Bearing that in mind, however, one way to help envisage the future of the Western Balkans and Moldova is by looking at what has happened in other former communist countries and neighbors.

When Poland joined the EU in 2004, followed by Bulgaria and Romania in 2007, one immediate effect was mass emigration. However, EU membership also gradually brought foreign investment and improving standards of living. Today while people still emigrate from all three countries it is no longer the mass emigration of the past and labor shortages mean that wages in all of them have been increasing for years. Poland, the richest of the three, is now a country of mass immigration. The populations of Bulgaria and Romania continue to shrink however but more thanks to low fertility than emigration.

In principle then, if the non-EU states of Southeast Europe continue to grow their economies and to (very) slowly converge with the EU, there is hope that things can change. But it is a big “if” and COVID-19 has disrupted the trends of the past few years. When the pandemic began, hundreds of thousands headed home to the Balkans and Moldova. There is little data on numbers but anecdotally we can tell that many who returned subsequently left again. You cannot drive a delivery truck or harvest asparagus remotely.

For office workers, the story is different and all of Southeast Europe stands to benefit if some of those who lived abroad and who returned home to work remotely can remain doing so while continuing to work for their foreign employers after the pandemic subsides. We are not however talking of huge numbers here.

The short to mid-term demographic future of Southeast Europe depends above all on what happens elsewhere. If the economic recovery is stronger in western and northern Europe then we can expect that, in the wake of its huge short-term disruption, previous migration trends will pick up once more.

Now, more than a year since the pandemic began, we can also see that birth rates are down in Southeast Europe, even more than could have been expected from gradually declining fertility rates. This is because families are worried about economic security and there is no reason to believe that they will all rush to make up for delayed births after COVID-19.

Policies and politics

Even if low birth rates worry governments, it is unclear what they can do about it. Still, in Serbia, the government is sufficiently concerned about the issue that in 2020 it created a Ministry of Family Welfare and Demography whose minister has ambitious plans. However, the state of Serbia’s post-pandemic finances will dictate what can actually be done.

At the same time, the governments of Southeast Europe will have been keeping a close eye on Poland and Hungary which, in the last few years, have funded expensive pro-natality policies. The problem is that the results are in and they are not promising. In both countries, birth rates are now lower than they were before their policies were instituted. They may create loyal voters, but it seems you can’t pay them to have babies. What is needed for that is economic security plus all sorts of inducements including affordable childcare and for women especially, job security.

To combat shrinking working-age populations Southeast European countries have already begun to increase pension ages or they will have to in the next few years. Productivity is low compared to the EU as are women’s employment rates. As elsewhere, large numbers of jobs are susceptible to automation and digitalization but there has been little or no research into the potential impact of such technological change in Southeast Europe and hence what it means for their economies, their people and demography in general.

For the last 15 years, politics in Southeast Europe have been dominated by the same familiar issues. They include Bosnia’s constitution, Serbia-Kosovo dialogue, Moldova “chooses between east and west,” increasing authoritarianism, the media under pressure and so on. All the while demographic pressures increase but slowly and hence almost imperceptibly for most people. Few if any countries have ever been in this situation before, that is to say of sagging birth rates, aging, high emigration and no immigration simultaneously and so, while it is hard to predict the future with certainty it is also unlikely that, in terms of demography, it portends anything good.

Tim Judah is a reporter and political analyst for The Economist, and has written several books on the Balkans, mainly focusing on Serbia and Kosovo.

This article appeared in the March 2021 issue of Helvetas Mosaic

Published at www.helvetas.org

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.