“There is no reason to think that in 30 years much of anything will be as it is today,” one of the editors of a new report on the Arctic climate said.

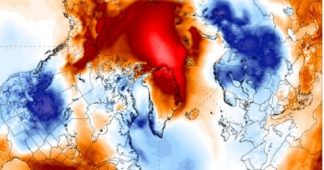

The Arctic continued its unwavering shift toward a new climate in 2020, as the effects of near-record warming surged across the region, shrinking ice and snow cover and fueling extreme wildfires, scientists said Tuesday in an annual assessment of the region.

Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at the University of Alaska and one of the editors of the assessment, said it “describes an Arctic region that continues along a path that is warmer, less frozen and biologically changed in ways that were scarcely imaginable even a generation ago.”

“Nearly everything in the Arctic, from ice and snow to human activity, is changing so quickly that there is no reason to think that in 30 years much of anything will be as it is today,” he said.

While the whole planet is warming because of emissions of heat-trapping gases through burning of fossil fuels and other human activity, the Arctic is heating up more than twice as quickly as other regions. That warming has cascading effects elsewhere, raising sea levels, influencing ocean circulation and, scientists increasingly suggest, playing a role in extreme weather.

This year the minimum extent of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean, reached at the end of the melt season in September, was the second-lowest in the satellite record, the scientists reported. On land, the huge Greenland ice sheet and glaciers in Alaska and elsewhere lost mass at above-average rates, although the rate in Greenland slowed from last year.

Permafrost, or permanently frozen ground, continued to thaw and erode along Arctic coastlines, leaving Indigenous communities struggling to cope with damaged infrastructure.

And perhaps most stunning, snow cover across the Eurasian Arctic reached a record low in June. The drying of soils and vegetation that followed contributed to wildfires that burned millions of acres of taiga, or boreal forest, particularly across Siberia. The fires spewed a third more heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than the year before, according to European researchers.

The amount of snow that fell across the Eurasian Arctic was actually above normal this year, said Lawrence Mudryk, a researcher with Environment and Climate Change Canada and lead author of the section on snow cover in the assessment. “Despite that, it was still warm enough that it melted faster and earlier than usual,” he said.

The warmth was pervasive across the Arctic. The average land temperature north of 60 degrees latitude, as measured from October 2019 through September, was 1.9 degrees Celsius, or 3.4 degrees Fahrenheit, above the baseline average for 1981-2010 and the second-highest in more than a century of record-keeping.

The outsized influence of the Arctic is why the assessment, called the Arctic Report Card, has been produced annually for the past 15 years by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. More than 130 experts from 15 countries contributed to this year’s version, which was issued at the annual conference of the American Geophysical Union.

In recent years Arctic researchers have increasingly come to recognize that the region is moving from a climate that is characterized less by ice and snow and more by open water and rain.

In a study published in September, two researchers with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colo., argued that for sea ice at least, a permanent shift had already occurred. Ice extent has now declined so much, Laura Landrum and Marika M. Holland wrote, that even an extremely cold year would not result in as much ice as was typical decades ago.

Donald K. Perovich, a professor at Dartmouth College and the lead author of the chapter on sea ice in the assessment, said that 2007 was a critical year. “We had the largest drop in ice extent we’d ever seen,” he said. “While there have been these variations since, we’ve never returned to those levels before 2007.”

“It’s as though we’re in this new state,” he said.

The age of sea ice is declining as well as the region warms. Three decades ago, ice that was at least four years old made up about a third of the Arctic Ocean pack ice at the end of winter. This year, according to the assessment, old ice accounted for less than 5 percent of the pack ice.

The increasing dominance of younger, and thus generally thinner, ice has contributed to the reduction in sea-ice extent, Dr. Perovich said, since thinner ice is less likely to last through a single season.