Arab nations are under pressure to act on Gaza. Radical measures have been suggested. But what can really be done?

Jan 30, 2024

It is often described as the world’s first oil crisis. In the early 1970s, oil-producing Arab states decided to impose an oil embargo on the United States and others, including the Netherlands and Portugal, to punish them for their support of Israel. In October 1973, Syria and Egypt had launched attacks on Israel in an attempt to recapture territory, including the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights, that Israel had occupied after Israeli-Arab fighting in 1967. Other Arab nations, such as leading oil-producer Saudi Arabia, supported the effort with the “oil weapon”, as it was described by some at the time.

The oil embargo ran until 1974 and had severe repercussions. Global oil prices rose by 300 per cent, sparking high inflation and causing gasoline shortages, and public fury in the US. But the embargo also helped force US diplomats to intervene in the region and bring the Egyptians and Israelis, who were fighting then, to the negotiating table. So why not use the “oil weapon” again now, some countries, including Algeria and Lebanon, suggested at a meeting in Saudi Arabia on 11 November, 2023, where Arab leaders discussed how they should react to the current Gaza conflict. The idea was quickly dismissed, with officials from Saudi Arabia, an essential player in any such embargo, rejecting it outright.

When it comes to reacting to the conflict in Gaza, Arab states face “a bit of conundrum”, says Khaled Elgindy, director of the Washington-based Middle East Institute’s program on Israeli-Palestinian affairs. “They are trying to balance various competing interests,” he told DW. “On one hand, they want to demonstrate to their own publics, which are extremely angry at both Israel and the US, that they are supportive of Palestinians. On the other, they do not want to do anything that could jeopardise their relations, with the US in particular, further enflame violence in the region or destabilise their own regimes.”

Under pressure to react

A global oil embargo would lead to “direct confrontation with the US and other Western nations,” Elgindy said, which is why it is unlikely. At the same time, Arab leaders are under increasing pressure to do something. The death toll in Gaza has climbed to more than 25,000 according to the enclave’s Hamas-run Health Ministry. The United Nations also warns that Gaza’s population is at risk of starvation and disease because of an ongoing Israeli blockade. Some Arab leaders, including senior politicians from Qatar and Jordan, have warned of the risk of regional war and increasing radicalisation among their own people.

The Arab League, an organisation for regional cooperation, issued a resolution after meeting in Cairo on 22 January, saying that Arab countries “will adopt all legal, diplomatic, and economic steps to prevent displacement of the Palestinian people” and a committee was formed to look into what those steps might entail.

What are the options? Some of the options are simply not logical, the Middle East Institute’s Elgindy explained. “A country like Jordan, which is among the most vocal in anger at Israel and the US, is not going to do something like facilitate weapons and fighters into the West Bank. That would be counterproductive since it would clearly lead to more violence and instability for both Jordan and the Palestinians, as well as strain relations with Israel and the US. But there are steps Arab leaders could take, he said, such as expelling Israeli ambassadors (even though many have already been evacuated due to anti-Israel protests), taking bolder steps to deliver aid without acquiescing to Israeli rules, preventing US weapons deliveries to Israel via US bases in Arab countries or joining South Africa’s court case against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), Elgindy suggested. “The fact that no Arab state has formally [joined the ICJ case] is striking,” he noted. Such a move “would certainly anger the US and, for those countries that have normalised ties, complicate relations with Israel. It could even trigger sanctions from the US. But such actions would likely be temporary.”

Experts: Don’t expect Arab unity

There is unlikely to be any truly coordinated or tangible response from Arab states, said Adel Abdel Ghafar, director of the Foreign Policy and Security program at the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, based in Qatar. “Each of them has their own foreign policy calculations, and even the Gulf states are divided on some of these issues,” he explained. “That has always been the weakness of coordinated Arab foreign policy.”

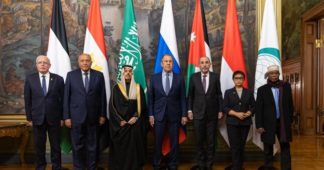

Where some Arab nations have shown unity is in working through multilateral institutions like the United Nations General Assembly, Abdel Ghafar continued, as well as working with non-Western powers, including China and Russia. He suggested Egypt and Jordan could do more individually, like accepting more medical cases or temporarily allowing displaced Palestinians. But it is unlikely any countries with treaties with Israel would withdraw from those. “These peace treaties are also connected to security collaboration and economic incentives from the US,” the Doha-based analyst explained.

Right now, the pressure point that is being pushed hardest is the threat of an end to the normalisation of relations between Israel and Arab states. An Arab-sponsored peace plan has recently been proposed which ties the prize of improved Israeli-Saudi ties to genuine progress towards a Palestinian state and therefore a permanent solution to the decades-old conflict. True peace in the region “is through a credible, irreversible progress towards a Palestinian state,” Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan told US television channel CNN on 21 January. “We are fully ready—not just as Saudi Arabia, but as Arab states—to engage in that conversation.” If Israel does not agree to this, bin Farhan stated that the offer is off the table.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has now said several times that he rejects the idea of a Palestinian state. And as Dina Esfandiary, a senior adviser at the International Crisis Group think tank, told the Bloomberg news agency, Arab states “know the Israelis are probably not going to sign up to something like this without significant pressure on them. ”But holding out the prize of normalisation with Saudi Arabia is about the only other option at the moment, Abdel Ghafar said, mainly because it seems Netanyahu is currently more motivated by domestic concerns and staying in power than any international issues, foreign allies or a united Arab front. The Saudi offer of normalisation is “just about the limit of coordination between Arab countries,” he said.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.