By William Mallinson

Athens, 15 October 2020

On 5 October, ekathimerini.com published an article by a Denis MacShane, né Josef Denis Matyjaszek, which can compete with some of the clumsiest, but hopefully accidental, propaganda that I have come across, and which does Greece a disservice. But first, for uninformed ekathimerini readers, who is MacShane? He is, as the article indeed describes him, the UK’s former Minister of [sic] Europe. What ekathimerini forgot to mention was that he is also a Blairite who supported the Iraq war, and a former jailbird, having spent six months in prison for false accounting seven years ago. Certainly not my cup of tea. Let us now consider his article, which is frightening for its ignorance, the result either of tactical omission or a lack of even basic knowledge about Anglo-Greek relations.

In his article, he quite rightly attacks Erdogan and Turkish policy, also referring to British pro-Turkish policy, particularly since post-Brexit, Britain will want to have a trade deal with the country. Let us however quote some of his article:

‘Two hundred years ago the people of Greece rose up and demanded freedom from their Turkish overlords. The campaign for Greek independence and sovereignty caught the imagination of the British people. The most famous of the many Brits who threw themselves whole-heartedly into the struggle for Greek freedom was the poet Lord Byron, who died in Greece while supporting the campaign.

Greece has always had a peculiar hold on the British or perhaps the English sensibility.

In the last two centuries our love affair with Greece has continued unabated. Patrick Leigh Fermor’s dashing exploits in World War II or Winston Churchill dropping everything to hurry to Athens for Christmas 1944 to stop a Soviet communist enslavement of Greece are examples. Christopher Hitchens, the famous leftist English polemicist, cut his teeth writing against the Turkish invasion and occupation of northern Cyprus and then a splendid book calling for the return of the Parthenon Marbles looted by a syphilitic Scottish aristocrat, Lord Elgin, who shamed British diplomacy and could only get away with his crime as Greece was still controlled by Istanbul.’

The unsuspecting reader may well assume that the British government loved Greece, and was in favour of Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire, when in fact the opposite was true. Is not MacShane aware that despite the simpering protestations of well-paid off designer academics in both Britain and Greece, British policy has been essentially antithetical to Greek interests since the very inception of the modern Greek state? For apart from a few flashes in the pan, and a few individuals like Canning, the only help Greece has received has been from private individuals such as Lord Byron, or public individuals who were brave enough to go against official British policy, such as Admiral Codrington, whose victory over the Turco-Egyptian fleet the irritated Foreign Secretary, Wellington, described as an ‘untoward event’, betraying a large measure of British understatement. For the British government never even wanted an independent Greece. She was only forced into giving way by the Russians, who had reserved the right by treaty to intervene alone to help Greece. Britain was therefore forced into helping, to keep a finger in the question, for fear of Russia ending up as Greece’s main sponsor, and weakening Britain’s Ottoman friends. The Don Pacifico Affair is another example, when Britain actually threatened Greece with gunboats; while during the Crimean War, Britain, with its then French poodles, blockaded Piraeus. In 1916, Britain and France even interfered militarily in Greece, being beaten back by the King’s forces, and then getting their revenge by backing the controversial Venizelos, who favoured war: Venizelos took Greece into a war which was to lead to the famous catastrophe. The next war is another example of Britain’s disdain. Despite the fact that Greece stood alone with Britain against all the odds, for several months, the help that Britain sent was minimal, and the British left, confusing many of the tough Greek fighters, who had already earned their spurs against the Italian invaders.

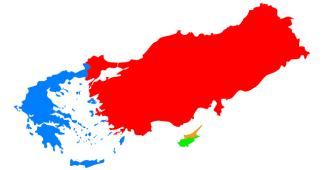

The Greek civil war is an even worse story: having supported the strongest anti-German resistance, ELAS, Britain then turned against it, ending up supporting those Greek forces which had been closest to the German occupiers, and fuelling a destructive civil war. As Woodhouse wrote, ‘the combined stubbornness of Churchill and the King was the proximate cause of the tragedy.’[1] It suited Britain, since it used the ‘anti-communist’ civil war as an excuse to hang elginistically on to Cyprus. Since then, the Cyprus question has continued to show that British policy is antithetical to Greek interests. In 1955, Britain colluded secretly with Turkey against Greece, brought Turkey illicitly into the Cyprus equation, and was aware of what the result would be, if not precisely: the destruction of Greek properties and churches in Turkey, and the subsequent expulsion of twelve thousand Greek nationals and hounding out of a further sixty thousand Turkish citizens of Greek stock and of the Christian Orthodox Church. Less than two thousand remain today. And all this, just so Britian could hang on to Cyprus for a little longer. As for more recently, the following quote from a Foreign and Commonwealth Office strategy paper encapsulates the backstage reality, whatever the fashionable criticism about Turkey’s absurd threats and sabre-rattling, which we have seen often in the past.

We should also recognise that in the final analysis Turkey must be regarded as more important to Western strategic interests than Greece and that, if risks must be run, they should be risks of further straining Greek rather than Turkish relations with the West.[2]

To summarise, MacShane’s lack of knowledge about Greece and Churchill’s damaging rôle does a disservice to factuality. His apparent support for Greece via criticism of Turkey and mentioning the Elgin marbles (currently fashionable) can of course be welcomed, but it detracts from the backstage reality about which so many Greeks are themselves still ignorant.

William Mallinson, a former British diplomat now based in Athens, is a diplomatic historian and author specialising, inter alia, in Anglo-Greek relations. He is Professor of Political Ideas and Institutions at Universitá Guglielmo Marconi,

——————–

[1] Woodhouse,. C.M., The Struggle for Greece, 1941-1949, C. Hurst and Co. Ltd., London, 2002, originally published in 1976 by Hart-Davis, MacGibbon Ltd. P.110. I find it bizarre that Veremis, Thanos M. and Koliopoulos, John S., in their book Greece, The Modern Sequel, Hurst and Company, London, 2002, do not mention Churchill’s malign rôle. I find it bizarre that Veremis, Thanos M. and Koliopoulos, John S., in their book Greece, The Modern Sequel, Hurst and Company, London, 2002, do not mention Churchill’s malign rôle.

[2] ‘British interests in the Eastern Mediterranean’, paper prepared by Western European Department, FCO, 11 April 1975, BNA FCO 46/1248, file DPI/516/1.