The Cretan Resistance caused significant damage to German morale and is likely one of the reasons why Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union was unsuccessful.

By Jessica Bateman

Aug 15, 2018

Our car pulled up a dusty track next to a grove of olive trees. My guide, Stelios Tripalitakis, got out and started briskly walking in between their gnarled trunks, stopping every couple of metres to investigate objects he spotted on the ground. I followed, desperately trying to keep up in the heavy Cretan heat.

“Ahhh, that’s just a bit of fence,” he said, disappointedly examining a piece of rusting metal.

Tripalitakis, 35, is one of Crete’s many wartime treasure hunters, devoting hours of his life to combing the island for military relics left behind when Nazis invaded the island during World War Two. Over the past two decades he’s managed to amass a collection of more than 40,000 items, transforming his living room into a makeshift museum.

As we hunted for items to add to his collection, Tripalitakis told me that around 70 German paratroopers killed by local villagers were buried on this unremarkable-looking piece of farmland. Although their bodies were transferred to an official cemetery in the nearby village of Malame in the 1960s, many personal items, such as helmets or gravity knives, were left behind. “This land has been cleaned by the farmer recently,” Tripalitakis said. “So perhaps I might find something new.”

Crete is a place where the past haunts the present. The island’s strategic position in the Mediterranean has sparked countless invasions, from the Venetians and Ottomans to, most recently, the Nazis.

Hitler’s army set its sights on Crete in May 1941 after its conquest of Greece the month before, launching an airborne attack on the island using glider and parachute forces. Crete’s residents joined 40,000 British, Greek, Australian and New Zealand troops in defending the island, often shooting down parachutes using their own rifles. However, the Allied forces misjudged the attack and, after an intense eight days of fighting, Crete fell to the Germans and the Allied forces withdrew.

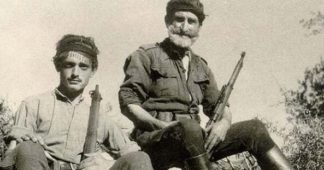

Feeling abandoned, the Cretans – who only four decades earlier had fought for and won their independence after 250 years of Ottoman occupation – came out of their homes and continued to challenge Hitler’s forces using whatever weaponry they had. It was the first time the Germans had encountered significant opposition from a local population. The Cretan Resistance is cited by The National Herald, an English-language Greek newspaper, as one of the factors that lead to the fatal delay of the the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, while also reducing the number of troops available for missions in the Middle East and in Africa. Despite repeated attacks from the Nazis on local villages and communities, the Cretan Resistance remained active until the Germans surrendered four years later, in 1945.

This period of history hugely shaped Cretan identity, and even the smallest villages contain a memorial. “Crete has always been liberated by itself. Everyone has always fought for their freedom,” Tripalitakis told me.

Tripalitakis’ hometown of Galatas, just outside the major city of Chania on the island’s north-west coast, was captured by the Germans on the sixth day of fighting. “When I was 12, the municipality of Galatas published a small magazine about the battle and gave it to all primary school pupils for free,” he remembered. “I was fascinated.”

His interest was also piqued by the military debris that still litters the island. “Everyone has relics from the war. Cretan people didn’t have many materials, so they used whatever they could find,” he said. As the Cretans worked to rebuild their homes, fences were constructed from rifle barrels, roofs from aircraft parts, and helmets were turned into flower pots or containers for animal feed. These can still be spotted in some more remote villages.

“I realised, when I was very young, that all these things had to be saved, because over time they get destroyed or thrown away,” Tripalitakis said. “It’s really important for people growing up to learn about our history. If we don’t show them these items, they won’t learn.”

Tripalitakis made his first searching trip in 1999, gathering pieces from a German aircraft wreckage on an islet off the coast of Galatas. Since then, he’s searched the entire island. “Sometimes I go once or twice a week, sometimes four,” he told me. “Sometimes I search for just a few hours. If I’m going into the mountains, I take a sleeping bag, food and water, and stay for a few days.” He’s even learnt how to scuba dive. “It’s so cool, feeling like you’re flying over a plane wreck.” Because of Crete’s many archaeological sites, collectors have to get permission from the authorities to use metal detectors. However, Tripalitakis usually prefers to search using just his eyes and hands.

However, luck wasn’t on our side that day – our thorough search of the olive grove failed to deliver any goods, so we drove the 10km back to Galatas for a look around his museum. I walked into the apartment he shares with his father and fiancée, and was greeted by four walls of floor-to-ceiling shelves crammed with every memento imaginable, from rifles to cooking equipment to dressmakers’ dummies wrapped in German and British uniforms. Pieces of gliders and parts of sub-machine guns spilled out of the apartment onto the terrace and driveway.

“I have everything, but there are still things I want, such as more motorcycles,” Tripalitakis said as he picked up a metal pot he had purchased from another collector the day before for 100 euros, and began to scrape the rust from it.

haul into unofficial museums. Other private collections can be found in the village of Askyfou in the Sfakia region, and in the villages of Somatas and Atispopoulo, south of Rethymno. Although none of these collectors lived through the war, they devote their time to preserving the stories of survivors, veterans and heroes of the Cretan Resistance.

“Sometimes there’s a bit of competition, but mostly we cooperate,” said Tripalitakis, adding that he’s even been made godfather to the child of a friend he met through collecting. “We put on exhibitions together, or sometimes we exchange things or go searching in pairs.”

Tripalitakis’ most valuable item is some landing gear from an American-made Brewster Buffalo aircraft – only three of which were ever deployed to Greece. “I found it in the sea, 100m deep and buried under sand,” he said. “It took me five days to retrieve it.” Another collector has offered him 10,000 euros for the item, but he refuses to sell.

Of course, some discoveries spark more powerful emotions than others. “I found the body of a New Zealand soldier, eight years ago,” Tripalitakis told me. “My metal detector got set off by the ammunition still on him. I think he had been buried by colleagues in a shallow grave. It was a shock to uncover it, but I actually felt happy to have found him, because I knew he could now get the proper burial and grave he deserved.” Tripalitakis called the police, who took the body for DNA testing. Since then, Tripalitakis has been desperately trying to find the man’s identity. “I’ve been through all the regiments and narrowed it down to 20 who are still missing,” he said.

Tripalitakis estimates his fuel for trips has cost 50,000 euros, and he has spent another 30,000 euros purchasing items from fellow collectors. His passion has tested his family’s patience; he admits his father isn’t keen on the apartment’s transformation. But Tripalitakis insists he’ll never sell his memorabilia, “even if I was offered a fortune”. Instead, his plan is to secure a warehouse and turn the collection into a more official museum.

“We cannot let the people forget history,” he said. “We keep it alive through these objects.”

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.