By Chris Walker*

Leaders from dozens of countries around the world have signed onto a joint statement calling for the creation of an international treaty that would address pandemics that will come about in the future.

In a joint press release published on Tuesday, leaders recognized that addressing future pandemics would require a joint global cooperative effort. The document outlined a number of possible ways in which the mitigation of outbreaks in the years ahead can be achieved, including the creation of a better joint alert system, data sharing and research between member states, and the sharing of supplies between countries in general, including personal protective equipment, medicines, diagnostics and vaccines.

Nations signing onto the document include countries from Asia, Africa, Europe and Latin America. The document also includes the support of the European Union and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Notably, leaders from the United States and China are not yet signatories to the document. But according to WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, both nations are receptive to the idea.

“From the discussions we had, during member states’ sessions, the comment from member states, including the U.S. and China, was actually positive and we hope future engagement will bring [in] all countries,” Tedros said.

The proposal issued on Tuesday recognizes that the current coronavirus pandemic was and is “the biggest challenge to the global community since the 1940s.” “There will be other pandemics and other major health emergencies. No single government or multilateral agency can address this threat alone,” the document says. “The question is not if, but when.”

Much like international agreements that were were created after World War II, the press release goes on to say that a pandemic treaty between member states is necessary for many of the same reasons — “to bring countries together, to dispel the temptations of isolationism and nationalism, and to address the challenges that could only be achieved together in the spirit of solidarity and cooperation, namely peace, prosperity, health and security,” the document states.

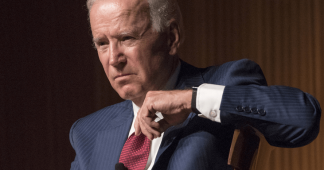

While officials from the U.S. may be reportedly open to the idea, getting legislative approval for such a treaty would be immensely difficult. The Senate must approve all treaties that are negotiated by the executive branch with two-thirds of that chamber concurring — meaning that, if President Joe Biden agrees to the terms of the treaty, it will not become recognized law in the U.S. without at least 17 Republican senators also agreeing to it in the evenly divided Senate.

There are ways around this, however. Similar to how the Paris Climate Accord was crafted, the final treaty may not be a formal treaty at all, but rather a commitment by member states to adhere to the principles shared in whatever the final document may end up being.

While such a move would allow Biden to commit to an international agreement without needing Senate approval, that approach also comes with risks. For instance, it makes enforcement of the final accord self-regulatory, wherein member countries could choose not to adhere to the terms of the agreement and face little consequence from an international agency after doing so.

A nonbinding commitment would also allow future presidential administrations that disagree with such an accord to drop the United States’s involvement with it entirely, much like former President Donald Trump did with the Paris climate agreement during his tenure in office

* Chris Walker is a news writer at Truthout, and is based out of Madison, Wisconsin. Focusing on both national and local topics since the early 2000s, he has produced thousands of articles analyzing the issues of the day and their impact on the American people.

Published at truthout.org