by Derek Davison and Jim Lobe

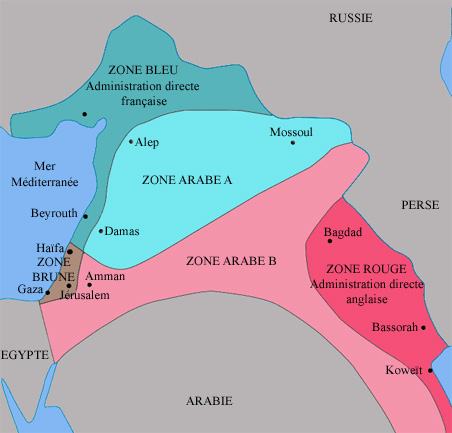

The 20th century was rife with partitions, many of them involving European powers carving up colonial possessions in Africa and the Middle East with what often appears to have been little or no concern for local realities. Perhaps the most famous of these free-hand attempts at state creation is the Sykes-Picot Line, whose legacy is very much still with us (and not for the better). But Sykes-Picot is far from the only example of European colonial borders that are still causing problems decades after they were drawn.

But who cares about all of that? It doesn’t seem to be an issue for at least some of America’s anti-Iran hawks. In response to Iran’s rising profile in the Middle East, fueled mostly by a war those neocons ardently championed and the striking ineptitude of the hawks’ new favorite Persian Gulf monarchy, the intellectual heirs to the men who drew those ill-fated borders are proposing, long after it might have done any good, to re-draw them.

Writing for Fox News on December 25, Michael Makovsky—who is no fringe figure, being CEO of the neoconservative Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs (JINSA)—suggests just such a strategy for countering Iranian influence in the Middle East:

Maintaining Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen in their existing forms is unnatural and serves Iran’s interests. There is nothing sacred about these countries’ borders, which seem to have been drawn by a drunk and blindfolded mapmaker. Indeed, in totally disregarding these borders, ISIS and Iran both have already demonstrated the anachronism and irrelevance of the borders.

Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen are not nation-states as Americans understand them, but rather post-World War I artificial constructs, mostly created out of the ashes of the Ottoman Empire in a colossally failed experiment by western leaders.

With their deep ethno-sectarian fissures, these four countries have either been held together by a strong authoritarian hand or suffered sectarian carnage.

It is astonishing to read neoconservatives, who have done little else since the 1970s but lobby for exerting American hegemony in the Middle East, decry the results of the exertion of European hegemony in the Middle East. It reads like an artificial intelligence that just briefly verges on full self-awareness before pivoting and falling back to safer ground. It’s particularly rich for Makovsky, whose JINSA predecessors promoted the ouster of two of those “strong authoritarian hands” in former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein and former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh, to bemoan one result of their ouster.

But let’s focus on the proposal Makovsky makes: redrawing borders in the Middle East, creating what he calls “loose confederations or new countries with more borders that more naturally conform along sectarian lines,” in order to counter Iran. The proposal strongly resembles recommendations found in “A Clean Break: A New Strategy for Securing the Realm,” a 1996 publication of the Jerusalem-based Institute for Advanced Strategic and Political Studies that was prepared in collaboration with several other neoconservative think tanks—including JINSA.

“A Clean Break,” the conclusion of a task force that included such Likudnik geniuses as Richard Perle, Douglas Feith, and David Wurmser, argued in part that Israel should work with friendly governments in Turkey and Jordan to contain regional threats, particularly coming from Syria. It concluded, among other things, that Israeli leaders should pursue “removing Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq-an important objective in its own right-as a means of foiling Syria’s regional ambitions.” “Syria” in this context serves as a stand-in for “Iran.” Long-term, the report envisioned the formation of a “natural axis” of Israel, Turkey, Jordan, and a “Hashemite” Iraq serving as “the prelude to a redrawing of the map of the Middle East, which could threaten Syria’s territorial integrity.”

Even a cursory glance at the state of the Middle East since the end of the Iraq War shows that ousting Saddam Hussein achieved the opposite of the report’s stated goals. The idea of a Hashemite restoration in Shia-majority Iraq was ridiculously far-fetched, and Iraq’s democratically-elected government has–justifiably–greatly improved the Baghdad-Tehran relationship. Makovsky, who wants to reverse this trend, argues that the United States should “declare our support and strong military aid for an eventual Iraqi Kurdish state, once its warring factions unify and improve governance. We could support a federation for the rest of Iraq.”

In Makovsky’s imagination, the new Kurd-less Iraqi federation would presumably wish Erbil well and send it on its way. In reality, another serious Kurdish move toward independence would probably lead to a civil war, as it nearly did in October over the status of Kirkuk. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s first foreign trip after his dramatic capture of Kirkuk was…to Iran. If the United States were to come out in full support of an independent Kurdistan, it would almost certainly push the rest of Iraq more firmly into Iran’s orbit. Speaking of Kirkuk, does Makovsky imagine that independent Kurdistan would be given the city and its surrounding oil fields? If yes, then that only increases the chances of a war with Baghdad. If no, then there are serious questions about whether that hypothetical Kurdish state would be economically viable.

For Syria, Makovsky says that “we could seek a more ethnically coherent loose confederation or separate states that might balance each other – the Iranian-dominated Alawites along the coast, the Kurds in the northeast, and the Sunni Arabs in the heartland.” He might want to check a recent map of Syria, because while “heartland” is obviously a subjective term, by almost any definition Syria’s “heartland” now belongs to President Basher al-Assad and his Russian and Iranian allies. This includes the country’s five largest (pre-war) cities: Aleppo, Damascus, Homs, Latakia, and Hama. How does Makovsky propose any of that territory be taken from Assad so as to be turned over to “Sunni Arabs,” even in a confederate sense? If the answer is “war,” then his Fox News thinkpiece is burying the lede to say the least.

Makovsky then recommends that the U.S. strengthen relations with Shia-majority Azerbaijan, in order to “demonstrate we are not anti-Shia Muslim.” Yes, that should do the trick. Of course, that’s not the only reason:

An added potential benefit of this approach could be a fomenting of tensions within Iran, which has sizable Kurdish and Azeri populations, thereby weakening the radical regime in Tehran.

You might even say that it could threaten Iran’s territorial integrity. Make a Clean Break, if you will.

The dangers of the United States trying to redraw Middle Eastern borders—Makovsky graciously allows that America “cannot dictate the outcomes” but should instead “influence” them—should be obvious. For one thing, there’s the immediate likelihood that attempting to draw new borders would intensify regional instability. For another, there’s little reason to expect that the United States would get the new borders any more “right” than Britain and France did a century ago, particularly not when the process is being managed by the same people who brought us the invasion of Iraq. For still another, the most recent example of such Western “influenced” partitioning isn’t exactly a positive one.

But we can’t leave Makovsky’s piece without mentioning its most jaw-dropping paragraph (emphasis ours):

Artificial states have been divided or loosened before with some success, such as the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, which are all post-WWI formations. Bosnia and Herzegovina have also managed as a confederation.

Czechoslovakia divided peacefully of its own accord. The Soviet Union more or less did likewise, though that dissolution hasn’t been quite so peaceful in recent years. As for Yugoslavia—well, maybe Dr. Makovsky’s definition of “success” is a bit different from most other people’s. To be fair, though, if the breakup of Yugoslavia is his template for the future of the Middle East, this piece makes a lot more sense.

But if Makovsky believes that federalizing existing Middle Eastern states along “ethno-sectarian” lines, why not start with Israel and the Occupied Territories, a notion that would seem logical to any 21st century mapmaker? After all, occupation of one people by another via a “strong authoritarian hand”—in this case the IDF—would seem to be a prescription for a “colossally failed experiment,” no? Perhaps Makovsky’s experience as a former West Bank settler may make it difficult for him to see the relevance.