By Michael Roberts

16 November 2017

Brazil faces a presidential election in October 2018. This will offer a new benchmark for which way Brazilian politics and the economy will go. Will a coalition of pro-big business parties and a president win or will a coalition led by the Workers party return to power under a leftist president (possibly Lula, the former president)?

Nobody I met in my visit to Brazil last week was sure what would happen. International capital is optimistic that the current neo-liberal administration will gain a four-year term, possibly under former vice-president Temer or maybe Sao Paulo Mayor Joao Doria, a businessman and former TV show host. Doria has expressed presidential ambitions and urged ‘centrist parties’ (ie pro-big business) to forge a common platform to combat ‘extremist candidates’ (Workers party). He appears to be Brazil’s version of Donald Trump. He wants to “gradually” sell off Brazil’s greatest state asset, oil giant Petrobras. “There is no need for Petrobras to keep being a state-owned company. Brazil is isolated in the world. We can’t be afraid to do what’s necessary to insert Brazil in the global and liberal economy,” he said. He is also in favour of privatizing Brazil’s electricity utility Eletrobras, ports, airports, railways, and waterways.

And he backs the usual neo-liberal measures (called “structural economic reforms”) designed to boost the rate of exploitation: weakening the unions; making it easier to fire workers; reducing their rights and conditions etc. He also wants to cut pension terms and cut taxes for the rich and corporations. “The next president will have to prioritize pension reform,” he says.

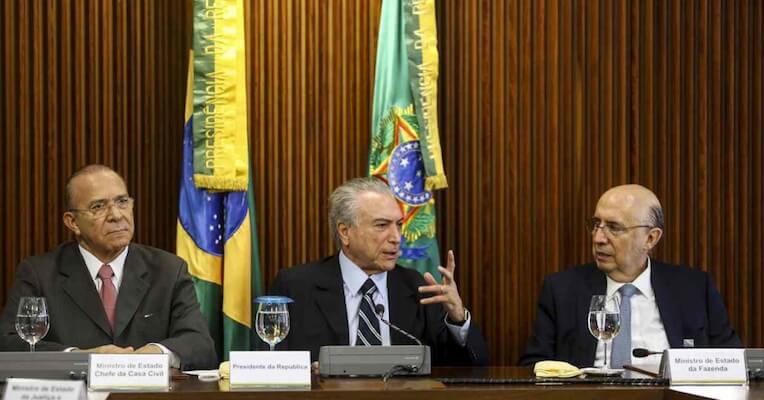

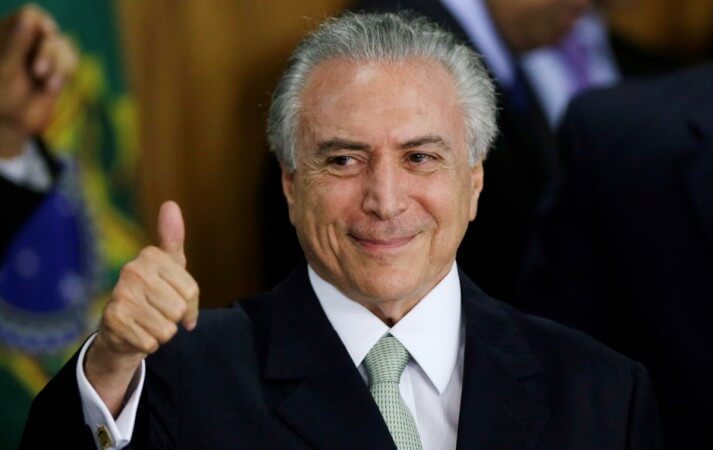

All this is much in line with the policies of the current President Temer who got the job after Congress (controlled by the right parties) managed to get elected Workers party President Dilma Rousseff impeached and removed on charges of corruption (operation car wash).

Interestingly, Doria does not agree with Trump on protectionism. In contrast, he wants a more “open economy” and a floating exchange rate. “We must avoid any protectionism that limits the country’s economic growth.” Doria also wants to preserve Brazil’s central bank independence – classic position of finance capital – keeping it out of democratic accountability. All this is pretty similar to Temer. Indeed, if Doria became president, he would probably keep the same economic and financial team as Temer has.

However, the problem for the pro-capitalist forces is that Doria and Temer’s economic platform is unpopular among the majority of Brazilians – not surprisingly. Indeed, Doria is careful to say that he will ‘preserve’ the highly popular Bolsa Familia benefit scheme for the poor that the Lula administration introduced. As the World Bank has shown, 62% of the decline in extreme poverty in Brazil between 2004 and 2013 was due to changes in non-labor income (mainly conditional cash transfers under the Bolsa Família program).

Also, Temer is extremely unpopular, with poll ratings well below even Trump’s in the US. That’s because he usurped the job from Dilmar and also avoided charges of corruption because of the backing of the right-wing majority in Congress. Lula is now the most popular politician in Brazil again and could win the presidency, except he too has been found guilty of corruption in the courts and thus faces being banned as a candidate.

Meanwhile, the big economic issue is whether Brazil can recover from the deep recession that it entered in 2014 and only now is making a mild and weak recovery.

Temer is relying on foreign investment from multi-nationals and speculative investor flows to sustain this limited recovery but he may well be disappointed. As a result of the slump, public sector debt has rocketed along with successive large deficits on the annual government budget.

Discretionary spending (education, health, transport etc) has been cut to the bone and now Temer, Doria and their backers want to destroy the state pension scheme in order to reduce debt and ‘balance the budget’.

Together with the increase in retirement age, the government is proposing the elimination of pensions by length of service and increasing from 15 to 25 the number of years of contributions necessary to qualify for an old age pension.

Brazil’s 27 states are also in deep trouble. Rio de Janeiro has had to delay payment of civil servant salaries (currently with a two months’ delay) and defaulted on its debt repayments. Rio Grande do Sul and Minas Gerais are also close to insolvency, while almost all other states are facing liquidity constraints and several are running up growing arrears with suppliers and employees. In response the Temer government wants to introduce a 20-year fiscal austerity plane and shift the debt of the states into the hands of a separate off-balance sheet agency that will ‘manage’ the debt using taxpayer revenues.

I participated in a public hearing at the Brazilian Senate committee on human rights and an international conference on this issue of debt. Both events were organised by Brazil’s Citizens Audit, a group with labour union support, that has been campaigning to explain why Brazil’s public debt is so high and the iniquity of the planned ‘privatising’ of debt management into the hands of the banking sector with losses for taxpayers and major liabilities.

I presented paper along with many other academics and activists from Latin America attending. In my paper, I emphasised the huge rise in public sector debt globally – the result of the bailouts of the global banking crash and subsequent global recession of 2008-9 – and the role played by international agencies in taking over the management of debt in distressed economies at the expense of public services.

In Brazil’s case, the public sector debt has always been high compared to other so-called emerging economies, despite public services being poor, because of very high interest rates on the debt and because tax revenues are relatively low.

The World Bank claims that “a large structural fiscal imbalance lies at the heart of Brazil’s present economic difficulties. While revenues are cyclical and have declined during the recession, spending is rigid and driven by constitutionally guaranteed social commitments, in particular on generous pension benefits.” So it is the fault of too much spending and too generous pensions, according to the World Bank. But this is ideological nonsense.

Brazil is the most unequal society in the G20 (apart from South Africa). But its tax system allows the richest income and wealth holders to get off lightly while the poor pay more – in other words, the tax system is very regressive and the tax base avoids the rich. As a result, interest costs on the public debt relative to tax revenues are the highest in the world.

Indeed, Brazil’s Oxfam has shown in a recent report that, if the tax system was made progressive; tax avoidance schemes were stopped; and tax evasion (including the use of offshore funds a la the Panama and Paradise papers) was ended, Brazil’s tax revenues would be more than enough to improve public services, protect pensions and social benefits.

The economic collapse of 2014-16 has been followed by a weak recovery. Indeed, the latest report on South America by the World Bank makes dismal reading. The bank says: “economic activity remains on track to recover gradually in 2017-18, but long-term growth remains stuck in low gear”. Growth has only turned positive because the world economy has picked up in the last year. As the bank says: “A favorable external environment is helping the recovery. Global demand is getting stronger and easy global financial conditions—low global market volatility and resilient capital inflows—are boosting domestic financial conditions.”

But “despite this ongoing recovery, prospects for strong long-term growth in Latin America and the Caribbean look dimmer. In the next 3-5 years, Latin America is projected to grow 1.7 percent in per capita terms. This growth rate is almost identical to the region’s performance over the past quarter century and only marginally better than those in advanced economies, raising concerns that the region is not catching up to income levels in advanced countries.”

The World Bank, along with the IMF, forecasts just 0.7% growth this year for Brazil and 1.5% in 2018. The domestic economy remains very weak. Industrial production is up only on exports. Capital investment remains down.

Average real incomes are still below the peak of 2014 even though inflation has dropped off from the recession.

The underlying reality is that Brazilian capital is still suffering from a long-term fall in its profitability from which it seems unable to escape, despite squeezing the labour force.

The World Bank points out that corporate debt as a share of GDP increased from an average of 23% of GDP in 2009 to 25% in December 2016) and a large share of corporates are overleveraged. It is Brazil’s capitalist sector that is in trouble. Naturally, the World Bank and the IMF suggest as solutions the usual batch of neo-liberal measures already adopted by Temer and proffered by Doria.

When the Brazilian economy boomed with the commodity price explosion of the 2000s, Brazil “experienced an unprecedented reduction in poverty and inequality” (World Bank) and 24 million Brazilians escaped poverty. And the gini coefficient of inequality of incomes fell from the shocking height of 0.59 to 0.51.

But after the recession of 2014-16 and under the Temer presidency, it is rising again. The international agencies, foreign investors and Brazilian big business want an administration in power for four more years from 2018 to impose austerity, labour ‘flexibility’ and privatisations. That will drive up inequality further. Ironically, it won’t reduce the public sector debt because economic growth and tax revenues will be too low. Indeed, the IMF forecasts debt will be much higher by 2002.

The World Bank sums up the state of affairs: “As the 2018 elections approach, the unity of the ruling coalition is likely to be increasingly tested. The 2018 presidential race remains very open and may result in new alliances which could reshuffle the political landscape. Further, the debate on the need for and the appropriate strategy to carry out fiscal adjustment and microeconomic reforms remains polarized.”

Source: The Next Recession