Diana Johnstone’s newly-published memoir offers an incisive, gritty, politically alert, and expansive account of post-war Europe, reports Patrick Lawrence in this interview with the author

By Patrick Lawrence

May 17, 2020

Diana Johnstone first sojourned in Paris during the early postwar years, as France and the rest of Europe were coming back to life—and as America set out to build an empire amid the Cold War frenzies of the McCarthy years.

Nearly seven decades later, Johnstone’s place among the distinguished Europe correspondents of our time lies beyond dispute. A Minnesota native, she is a French citoyen now and remains a Parisienne. “If I must claim a label,” Johnstone, 89, writes in her just-published personal and political memoir, “it would be that of an independent truth-seeker.”

Circle in the Darkness (Clarity Press) —Johnstone takes the title from Einstein—is a moving, incisive, gritty, politically alert, and always humane account of Johnstone’s long decades as a Europeanist. In the interview that follows, we touched on many of the topics she has long covered in her news reports, commentaries, and books: the trans–Atlantic rift, the fate of the European Union, Europe’s search for an independent voice and the Continent’s relations with Russia. She told me: “I think there is increasing desire to escape from the clutches of the American empire, but what is needed is the right moment and leaders capable of seizing it.”

decades as a Europeanist. In the interview that follows, we touched on many of the topics she has long covered in her news reports, commentaries, and books: the trans–Atlantic rift, the fate of the European Union, Europe’s search for an independent voice and the Continent’s relations with Russia. She told me: “I think there is increasing desire to escape from the clutches of the American empire, but what is needed is the right moment and leaders capable of seizing it.”

I conducted this interview via email over the course of several months, during which the spread of the Covid–19 virus confined Johnstone to her Paris apartment. Per usual, she had a take on the political ramifications of this global calamity. “The Covid–19 crisis makes it just that much clearer that the European Union is no more than a complex economic arrangement,” Johnstone said toward the end of our exchange, “with neither the sentiment nor the popular leaders that hold together a nation.”

P.L. You’ve known France and Europe through all sorts of phases—postwar reconstruction, the so-called trente glorieuses [1945–75], the ’68 “events” and their aftermath, the drift away from a native social democracy toward Anglo–American neoliberalism. How would you describe this arc? What has propelled Europe in the direction it has taken—which, maybe you agree, is an unfortunate trajectory? I suppose I’m looking for historical context and causality.

D.J. That’s a very big question, which is hard for me to answer without going on and on. I suppose you could describe this arc in terms of the Americanization of France, which has risen over the decades and may be declining mainly because America’s attractiveness as a model is declining, not only in France.

Shall we look at the history?

French soldiers guarding a Metro entrance in Paris, France at the beginning of World War I.(Bain News Service/Wikimedia Commons)

You have to go back to the First World War to understand the process. The war of 1914 to 1918 bled the youth of the nation—over half the armed men were casualties, with heavy losses among the young officers. France came out of that horrendous bloodbath among the victors, got back Alsace–Lorraine, and was exhausted, more than willing to consider that one “war to end all wars” was enough. Germany was also bled but came out bitterly resentful, with the results we all know: a second war meant to correct the first. What I’m getting at is that the French reluctance to fight another war with Germany cannot be explained—as some do—by latent sympathy for Nazi ideas, although such sympathy existed throughout Europe at the time—more so, surely, in Britain. It’s simply that in France, the feeling of being eager to die for a righteous cause had been used up 20 years earlier.

France’s rapid surrender to the German blitz in 1940 was a trauma whose scars have never been healed. The role of “the Resistance,” with a capital “R,” was mainly to salvage what could be salvaged of national pride. It also prepared for the social democracy of the postwar period, with the program of the Conseil National de la Résistance (CNR, National Resistance Council), accepted across the political spectrum as necessary for national unity. It called for universal social security, nationalization of banks and key industries, women’s suffrage—finally!—and other social measures.

Interesting. These connections are not much appreciated in the U.S. How does your own experience fit with this history, “an American in Paris”?

I first made acquaintance with Paris in the mid–1950s. It was not in ruins like Germany or damp and dreary as London, but my impression was that morale was not high. You could feel an underlying resistance to America’s whopping shadow, in some ways a continuation of the passive resistance to Nazi occupation, as most resistance is always passive. The more tangible resistance came from more or less the same players as the Resistance against Nazi occupation: the French Communist Party and conservative patriots.

In Eastern Europe, the new Russian occupation was military and political. In France, the American occupation was only slightly military but primarily cultural. Its beginnings showed the happy face of American jazz. You could even be a bit anti–American and love jazz thanks to the black musicians.

And jazz by no means drove out the internationally popular French singers who provided part of the background music of the era: Georges Brassens, Edith Piaf, Juliette Greco, Charles Trenet, Yves Montand, many more. Although vaguely demoralized, Paris still aspired to the role of vanguard of intellectual life, thanks to “existentialism”—not only the worldwide prestige of Jean–Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, but a lifestyle appropriate to recovering from a bad illness.

In those days you could open your window to street singers and throw them a little money. And there were the men who walked through the city with sheets of glass on their backs crying “Vitrier! Vitrier!” [Glazier! Glazier!] on the chance that your windowpane was broken and you needed to have it fixed.

And there were the movies, black-and-white but never Manichean. Without putting the word on it, that was what first won me over: the absence of the emphatic moral dualism of American movies. Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête, the wistful amoralism of young Gérard Philippe in Le diable au corps—no actor was showing off how good he was, and there was no one to hate.

Meanwhile in the ’50s, France was losing colonial wars in Indochina and North Africa, and its politics were like the game of pick-up-sticks.

In 1958, de Gaulle took over, going on to end both American military occupation and French colonialism, choosing to seek independent relations with the whole world. Culture Minister André Malraux returned the blackened façades of Paris buildings to their original cream color, industry flourished, French “New Wave” cinema excelled.

Thank you. Wonderful context. Let’s keep going into the ’60s.

The paradox of the ’60s was that just as de Gaulle was de–Americanizing France on the geopolitical level, the totally baby-boom postwar generation was Americanizing in its own peculiar way. As the country prospered, a squeaky-clean new generation clumsily Americanized with the “YéYé” singers, “surprise parties,” “flirts”, and “standing” (instead of the good French word prestige).

The celebrations of Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six Day War were closely followed by a fresh focus on the crimes of the Occupation, notably the deportation of Jews. This plunged the nation into guilt—a guilt the young generation avoided by dissociating from the nation.

You’re talking about that period when the export of American culture was turned into a Cold War weapon.

America was innocent. The fascination with a mythical America, spread worldwide by the U.S. entertainment industry, often with government sponsorship, still prepares people to despise their own country as backward. This sets the stage for fatalistic acceptance of U.S. pressure to conform to the U.S. concept of American exceptionalism even in world affairs. This was only temporarily set back by the war in Vietnam—the Americans themselves were against the war, weren’t they? I was one of those who helped make it seem that way.

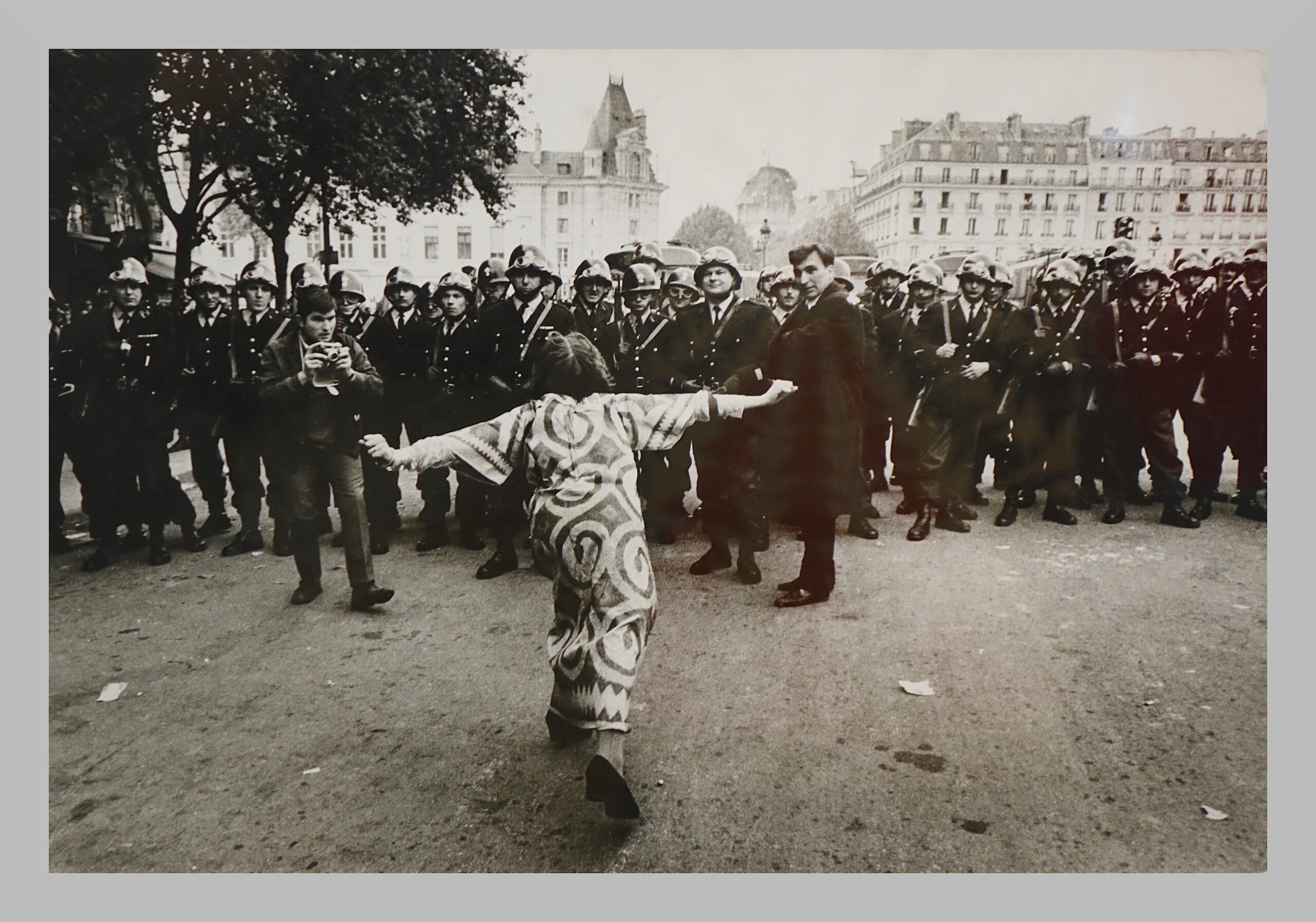

The May ’68 generation, which had grown up as things got steadily better, rejected both the authority of Gaullist paternalism and the discipline of the Communists. The result was a hedonistic individualism, intellectualized by Foucault [Michel Foucault, the late philosopher and theorist] and others as “resistance” to ubiquitous “power.” In this respect, by its “theorists,” French philosophy actually hastened the Americanization of France, and even of America itself. By constantly attacking, deconstructing, and denouncing every remnant of human “power” they could spot, the intellectual rebels left the power of “the markets” unimpeded, and did nothing to stand in the way of the expansion of U.S. military power all around the world.

The “anti-power” generation ended up condemning its own country, France, for its colonial past, while showing scant concern over the overwhelming current power of the United States as it destroys one country after another—sometimes with France taking part, as in Libya. There is also the fact, hard to demonstrate in detail, that through networks like the Young Leaders program of the French–American Foundation, United States officials get a crack at indoctrinating, selecting, or at least vetting up-and-coming French political personalities.

So well explained, Diana. And we come to the neoliberal phase, which has always struck me as odd, given it derived from the Anglo–American tradition, not the Continent’s.

With Emmanuel Macron, France seems to have the anti–de Gaulle, the most American president ever. And that may help trigger a change of course. Donald Trump is also, in his way, the most “American” president in recent times, in ways that do not appeal to people in Europe. The United States looks more and more like a madhouse, and its foreign policy threatens the interests and even survival of Europe, so the time has come for the arc to descend.

At what point and why did Europe surrender its independence within the Atlantic alliance—or did it never, during the early postwar years, achieve any independence to speak of?

The whole point of the Atlantic alliance was to institutionalize Western Europe’s surrender of its independence. And that was decided at Yalta—where Western Europe was not represented, not even by France, to the great chagrin of de Gaulle. There was an attempt at independence in the decade of President de Gaulle. But this bold course did not gain overwhelming domestic support. The only other independent European leader was Olof Palme [Swedish prime minister, 1969–76; 1982 until his assassination in 1986], but Sweden was not part of the Atlantic alliance and Palme’s relative neutrality was always heartily disliked by most of the Swedish upper classes and military leaders.

Can you reflect upon de Gaulle in this context? He is not much understood among Americans—not for his insistence on French independence and certainly not for his economic and industrial policies—his conception of society altogether. Can you say a little about this, and de Gaulle’s idea of French, and by extension European independence? Should we think of his domestic program as of a piece with his thoughts on the international side?

Not much understood? I’d say he has been totally and willfully misunderstood. There are relatively few Americans who can begin to understand a leader determined to maintain his country’s independence from America, and those few have generally had to live abroad to get the point. De Gaulle was a conservative, not a free-market liberal, who saw social reforms benefiting the working class as necessary for national coherence. The mixed economy he favored is not altogether unlike “socialism with Chinese characteristics”—a strong state role to encourage rapid industrial growth, with the rest left to free enterprise. It was a most successful formula. Of course, the political system was quite different.

Having a sense of history, de Gaulle saw that colonialism had been a moment in history that was past. His policy was to foster friendly relations on equal terms with all parts of the world, regardless of ideological differences. I think that Putin’s concept of a multipolar world is similar. It is clearly a concept that horrifies the exceptionalists.

De Gaulle had an organic concept of the nation, a living thing that develops its own identity, and in this view each nation needs to be able to live its own life. This is a conservative, not an aggressive nationalism. The United States is an ideological nation, whose “values” and institutions should be welcomed or imposed everywhere. France has tried that, with Napoleon Bonaparte. The retreat from Moscow [ending Bonaparte’s Russian campaign in 1812] is a lesson to be learned in Washington.

Is there any Gaullist streak in French or European discourse today? He certainly left his mark elsewhere—there is a self-consciously Gaullist strain in Japanese thinking, for instance—often submerged but ever there, the impulse to break free of the suffocating embrace, let’s call it. Any such thing in France or elsewhere in Europe today?

President Kennedy and President De Gaulle at the conclusion of their talks at Elysee Palace, Paris, France, June 2, 1961. (John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston)

Fifty years after his death, just about everyone in France claims to be “Gaullist.” They certainly aren’t, but this indicates that there is deep dissatisfaction with the way things are going. I think there is increasing desire to escape from the clutches of the American empire, but what is needed is the right moment and leaders capable of seizing it.

Do you think “the right moment” is upon us or approaching? There are certainly signs of it—all the dissatisfaction Trump has provoked, the extraordinary “declarations of independence” that followed the disastrous NATO and G–7 summits in 2017. What is your reading of “the moment”?

Amazing. Just as you were asking about the big moment, here comes a big moment that is not what any of us were expecting. This sudden disruption of our lives by a virus is a reminder that the future is always unknown and predictions are vain.

The dissatisfactions that were building up before the pandemic hit are all there, many of them exacerbated by the health crisis—but also overshadowed by the new problems it creates. During months of Yellow Vest protests and strikes against government austerity measures, nurses were in the forefront, braving violent repression to protest against their deteriorating working conditions. The Covid–19 crisis has shown just how right they were! They are now popularly regarded as heroes.

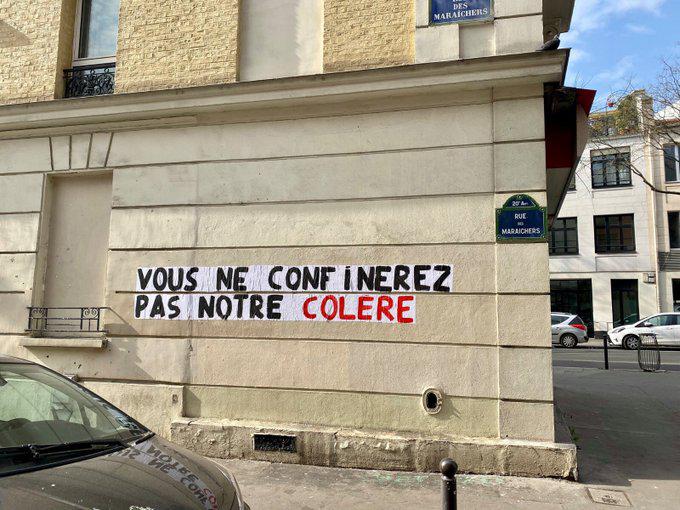

So long as we’re on the subject, what has been the general response to officially ordered confinements during the Covid–19 crisis? Over here we’re seeing mounting protests against them—people demanding that restrictions ease.

In France, confinement has been generally well accepted as necessary, but that does not mean people are content with the government—on the contrary. Every evening at eight, people go to their windows to cheer for health workers and others doing essential tasks, but the applause is not for President Macron.

Macron and his government are criticized for hesitating too long to confine the population, for vacillating about the need for masks and tests, or about when or how much to end the confinement. Their confusion and indecision at least defend them from the wild accusation of having staged the whole thing in order to lock up the population.

What we have witnessed is the failure of what used to be one of the very best public health services in the world. It has been degraded by years of cost-cutting. In recent years, the number of hospital beds per capita has declined steadily. Many hospitals have been shut down and those that remain are drastically understaffed. Public hospital facilities have been reduced to a state of perpetual saturation, so that when a new epidemic comes along, on top of all the other usual illnesses, there is simply not the capacity to deal with it all at once.

The neoliberal globalization myth fostered the delusion that advanced Western societies could prosper from their superior brains, thanks to ideas and computer startups, while the dirty work of actually making things is left to low-wage countries. One result: a drastic shortage of face masks. The government let a factory that produced masks and other surgical equipment be sold off and shut down. Having outsourced its textile industry, France had no immediate way to produce the masks it needed.

Meanwhile, in early April, Vietnam donated hundreds of thousands of antimicrobial face masks to European countries and is producing them by the million. Employing tests and selective isolation, Vietnam has fought off the epidemic with only a few hundred cases and no deaths.

You must have thoughts as to the question of Western unity in response to Covid–19.

In late March, French media reported that a large stock of masks ordered and paid for by the southeastern region of France was virtually hijacked on the tarmac of a Chinese airport by Americans, who tripled the price and had the cargo flown to the United States. There are also reports of Polish and Czech airport authorities intercepting Chinese or Russian shipments of masks intended for hard-hit Italy and keeping them for their own use.

The absence of European solidarity has been shockingly clear. Better-equipped Germany banned exports of masks to Italy. In the depth of its crisis, Italy found that the German and Dutch governments were mainly concerned with making sure Italy pays its debts. Meanwhile, a team of Chinese experts arrived in Rome to help Italy with its Covid–19 crisis, displaying a banner reading “We are waves of the same sea, leaves of the same tree, flowers of the same garden.” The European institutions lack such humanistic poetry. Their founding value is not solidarity but the neoliberal principle of “free unimpeded competition.”

How do you think this reflects on the European Union?

The Covid–19 crisis makes it just that much clearer that the European Union is no more than a complex economic arrangement, with neither the sentiment nor the popular leaders that hold together a nation. For a generation, schools, media, politicians have instilled the belief that the “nation” is an obsolete entity. But in a crisis, people find that they are in France, or Germany, or Italy, or Belgium—but not in “Europe.” The European Union is structured to care about trade, investment, competition, debt, economic growth. Public health is merely an economic indicator. For decades, the European Commission has put irresistible pressure on nations to reduce the costs of their public health facilities in order to open competition for contracts to the private sector—which is international by nature.

Globalization has hastened the spread of the pandemic, but it has not strengthened internationalist solidarity. Initial gratitude for Chinese aid is being brutally opposed by European Atlanticists. In early May, Mathias Döpfner, CEO of the Springer publishing giant, bluntly called on Germany to ally with the U.S.—against China. Scapegoating China may seem the way to try to hold the declining Western world together, even as Europeans’ long-standing admiration for America turns to dismay.

Meanwhile, relations between EU member states have never been worse. In Italy and to a greater extent in France, the coronavirus crisis has enforced growing disillusion with the European Union and an ill-defined desire to restore national sovereignty.

Corollary question: What are the prospects that Europe will produce leaders capable of seizing that right moment, that assertion of independence? What do you reckon such leaders would be like?

The EU is likely to be a central issue in the near future, but this issue can be exploited in very different ways, depending on which leaders get hold of it. The coronavirus crisis has intensified the centrifugal forces already undermining the European Union. The countries that have suffered most from the epidemic are among the most indebted of the EU member states, starting with Italy. The economic damage from the lockdown obliges them to borrow further. As their debt increases, so do interest rates charged by commercial banks. They turned to the EU for help, for instance by issuing eurobonds that would share the debt at lower interest rates. This has increased tension between debtor countries in the south and creditor countries in the north, which said nein. Countries in the eurozone cannot borrow from the European Central Bank as the U.S. Treasury borrows from the Fed. And their own national central banks take orders from the ECB, which controls the euro.

What does the crisis mean for the euro? I confess I’ve lost faith in this project, given how disadvantaged it leaves the nations on the Continent’s southern rim.

The great irony is that “a common currency” was conceived by its sponsors as the key to European unity. On the contrary, the euro has a polarizing effect—with Greece at the bottom and Germany at the top. And Italy sinking. But Italy is much bigger than Greece and won’t go quietly.

The German constitutional court in Karlsruhe recently issued a long judgment making it clear who is boss. It recalled and insisted that Germany agreed to the euro only on the grounds that the main mission of the European Central Bank was to fight inflation, and that it could not directly finance member states. If these rules were not followed, the Bundesbank, the German central bank, would be obliged to pull out of the ECB. And since the Bundesbank is the ECB’s main creditor, that is that. There can be no generous financial help to troubled governments within the eurozone. Period.

Is there a possibility of disintegration here?

The idea of leaving the EU is most developed in France. The Union Populaire Républicaine, founded in 2007 by former senior functionary François Asselineau, calls for France to leave the euro, the European Union, and NATO.

The party has been a didactic success, spreading its ideas and attracting around 20,000 active militants without scoring any electoral success. A main argument for leaving the EU is to escape from the constraints of EU competition rules in order to protect its vital industry, agriculture, and above all its public services.

A major paradox is that the left and the Yellow Vests call for economic and social policies that are impossible under EU rules, and yet many on the left shy away from even thinking of leaving the EU. For over a generation, the French left has made an imaginary “social Europe” the center of its utopian ambitions.

“Europe” as an idea or an ideal, you mean.

Decades of indoctrination in the ideology of “Europe” has instilled the belief that the nation-state is a bad thing of the past. The result is that people raised in the European Union faith tend to regard any suggestion of return to national sovereignty as a fatal step toward fascism. This fear of contagion from “the right” is an obstacle to clear analysis which weakens the left… and favors the right, which dares be patriotic.

Two and a half months of coronavirus crisis have brought to light a factor that makes any predictions about future leaders even more problematic. That factor is a widespread distrust and rejection of all established authority. This makes rational political programs extremely difficult, because rejection of one authority implies acceptance of another. For instance, the way to liberate public services and pharmaceuticals from the distortions of the profit motive is nationalization. If you distrust the power of one as much as the other, there is nowhere to go.

Such radical distrust can be explained by two main factors—the inevitable feeling of helplessness in our technologically advanced world, combined with the deliberate and even transparent lies on the part of mainstream politicians and media. But it sets the stage for the emergence of manipulated saviors or opportunistic charlatans every bit as deceptive as the leaders we already have, or even more so. I hope these irrational tendencies are less pronounced in France than in some other countries.

I’m eager to talk about Russia. There are signs that relations with Russia are another source of European dissatisfaction as “junior partners” within the U.S.–led Atlantic alliance. Macron is outspoken on this point, “junior partners” being his phrase. The Germans—business people, some senior officials in government—are quite plainly restive.

Russia is a living part of European history and culture. Its exclusion is totally unnatural and artificial. Brzezinski [the late Zbigniew Brzezinski, the Carter administration’s national security adviser] spelled it out in The Great Chessboard: The U.S. maintains world hegemony by keeping the Eurasian landmass divided. But this policy can be seen to be inherited from the British. It was Churchill who proclaimed—in fact welcomed—the Iron Curtain that kept continental Europe divided. In retrospect, the Cold War was basically part of the divide-and-rule strategy, since it persists with greater intensity than ever after its ostensible cause—the Communist threat—is long gone.

I hadn’t put our current circumstance in this context.

The whole Ukrainian operation of 2014 [the U.S.–cultivated coup in Kyiv, February 2014] was lavishly financed and stimulated by the United States in order to create a new conflict with Russia. Joe Biden has been the Deep State’s main front man in turning Ukraine into an American satellite, used as a battering ram to weaken Russia and destroy its natural trade and cultural relations with Western Europe.

U.S. sanctions are particularly contrary to German business interests, and NATO’s aggressive gestures put Germany on the front lines of an eventual war.

But Germany has been an occupied country—militarily and politically—for 75 years, and I suspect that many German political leaders (usually vetted by Washington) have learned to fit their projects into U.S. policies. I think that under the cover of Atlantic loyalty, there are some frustrated imperialists lurking in the German establishment, who think they can use Washington’s Russophobia as an instrument to make a comeback as a world military power.

But I also think that the political debate in Germany is overwhelmingly hypocritical, with concrete aims veiled by fake issues such as human rights and, of course, devotion to Israel.

We should remember that the U.S. does not merely use its allies—its allies, or rather their leaders, figure they are using the U.S. for some purposes of their own.

What about what the French have been saying since the G–7 session in Biarritz two years ago, that Europe should forge its own relations with Russia according to Europe’s interests, not America’s?

I think France is likelier than Germany to break with the U.S.–imposed Russophobia simply because, thanks to de Gaulle, France is not quite as thoroughly under U.S. occupation. Moreover, friendship with Russia is a traditional French balance against German domination—which is currently being felt and resented.

Stepping back for a broader look, do you think Europe’s position on the western flank of the Eurasian landmass will inevitably shape its position with regard not only to Russia but also China? To put this another way, is Europe destined to become an independent pole of power in the course of this century, standing between West and East?

At present, what we have standing between West and East is not Europe but Russia, and what matters is which way Russia leans. Including Russia, Europe might become an independent pole of power. The U.S. is currently doing everything to prevent this. But there is a school of strategic thought in Washington which considers this a mistake, because it pushes Russia into the arms of China. This school is in the ascendant with the campaign to denounce China as responsible for the pandemic. As mentioned, the Atlanticists in Europe are leaping into the anti–China propaganda battle. But they are not displaying any particular affection for Russia, which shows no sign of sacrificing its partnership with China for the unreliable Europeans.

If Russia were allowed to become a friendly bridge between China and Europe, the U.S. would be obliged to abandon its pretensions of world hegemony. But we are far from that peaceful prospect.

Patrick Lawrence, a correspondent abroad for many years, chiefly for the International Herald Tribune, is a columnist, essayist, author and lecturer. His most recent book is “Time No Longer: Americans After the American Century” (Yale). Follow him on Twitter @thefloutist. His web site is Patrick Lawrence. Support his work via his Patreon site.

Published atconsortiumnews.com