By John Braddock

30 January 2017

The release early last week of thousands of files related to New Zealand by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) further demolishes the myth of the now-deceased Labour Party Prime Minister David Lange (in office from 1984 to 1989) as a crusader against nuclear weapons.

The database was put online after legal action by the US-based MuckRock group, set up to help people file Freedom of Information Act requests. Among 13 million pages of records are almost 4,000 CIA documents referencing New Zealand, dating from 1948.

Outgoing US Ambassador to New Zealand Mark Gilbert told the New Zealand Herald the documents came from “note-taking in diplomatic meetings” and that the US “does not spy on New Zealand.”

Such claims are manifestly false. There is material in the CIA documents, which are heavily redacted, that could only have been collected by clandestine means. This includes a 12-page report from 1949 on the Stalinist Communist Party of NZ, discussing the extent of its influence within the Labour Party and trade unions. The Herald noted that coding on some of the sensitive documents indicates that their circulation was limited to high levels of the US government.

Many documents deal with the Lange government, which barred US warships from entering New Zealand. Washington was concerned about widespread opposition to nuclear weapons testing and the potential for Moscow to take advantage to increase its influence in the Pacific, which the US has always regarded as its back yard.

Under the Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament and Arms Control Act, passed by the Labour government in 1987, the country’s territorial sea, land and airspace became nuclear-free zones. After the law was passed, Washington suspended the tripartite ANZUS defence treaty, which included Australia.

While NZ-US defence ties have been fully restored and strengthened, particularly since 2001, the anti-nuclear policy has remained in place and is frequently trumpeted as the basis of the country’s “independent foreign policy.” In a July 2016 speech, Labour leader Andrew Little praised it as a “core part of New Zealand’s international identity,” now supported by “all sides of the political divide.”

The CIA documents show that Labour’s pacifist posturing was always a cynical charade. The party represents the interests of the New Zealand ruling class that, since World War II, has maintained a close alliance with the US in order to advance its own neo-colonial interests in the South Pacific.

According to the Herald, Lange’s newly-elected government in 1984 immediately tried to find a loophole in the policy to allow continued visits by US warships and “save the NZ and US relationship.”

Lange told US officials he believed nuclear propulsion was safe, leading the CIA to conclude that Lange had backed himself into a corner by campaigning on the anti-nuclear issue. The proposed visit by the USS Buchanan in 1985 was eventually denied on the basis that Washington refused to “confirm or deny” if it was nuclear armed.

A CIA report from 1985 stated that Labour MP Mike Moore, briefly prime minister in 1990 and later New Zealand ambassador to Washington (2010–15), told US embassy officials in 1984 “the United States should ‘finesse’ the nuclear power issue by asking to send a conventionally powered ship.” Moore said it “should ‘tell David [Lange] privately’ that no nuclear weapons would be on board the ship requesting access.”

Gerald Hensley, then head of the prime minister’s department, told the Herald Lange had secretly worked on a similar plan with the US Embassy. Chief of Defence Ewan Jamieson was to be sent to Hawaii to choose a ship obviously unable to carry nuclear weapons or sail under nuclear propulsion. The USS Buchanan was the vessel NZ selected to break the deadlock.

News of the proposal leaked while Lange was overseas. Acting Prime Minister Geoffrey Palmer refused the USS Buchanan entry after Labour MP Jim Anderton said he would publicly protest the visit. A CIA report suggested Anderton would have had majority support in Labour’s parliamentary caucus.

Another former cabinet minister, Richard Prebble, said shortly after this “came the invitation to debate the issue at the Oxford Union and Lange’s evolution into a nuclear-free warrior.” Lange went to Oxford and argued before an international television audience that “nuclear weapons are morally indefensible.” According to Prebble, “the public reaction to little New Zealand standing up to America was euphoric.”

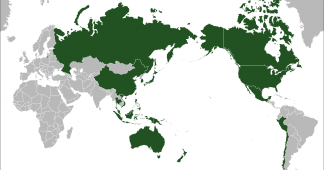

Behind the scenes, however, Labour worked assiduously to maintain ties with Washington. This included granting certain exemptions to the anti-nuclear legislation for visiting US military aircraft. More significantly, Labour vastly expanded the spy agencies, and in 1987 sought to appease the US by constructing the Waihopai spy base and boosting New Zealand’s contribution to the US-led Five Eyes spy alliance.

The Labour governments of the 1970s and 1980s were not concerned about “peacemaking.” Their opposition to nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific was bound up with the determination of both Australia and New Zealand to continue to hold sway over the region, particularly in opposition to France, which was conducting nuclear tests in the South Pacific.

The anti-nuclear posturing served a fundamental purpose for the New Zealand ruling class. It provided a “left wing” veneer for Labour as it launched far-reaching pro-market “reforms,” imposing the same policies as Thatcher in Britain and Reagan in the US on behalf of big business and the financial elite, with devastating consequences for the working class.

Hensley told the Herald there was a “rumoured” trade-off between the different factions of the Labour caucus: there would be “no opposition” to the right-wing economic agenda so long as Lange made New Zealand nuclear-free.

Regardless of whether there was such a deal, as the anti-nuclear policy gained wider support, especially among the middle class, Labour proceeded to deregulate the financial sector, privatise government-owned corporations, slash taxes for the rich and introduce the regressive Goods and Services Tax. The result was soaring social inequality. Tens of thousands of workers abandoned the Labour Party in disgust.

In 1989 Anderton quit the Labour Party to set up NewLabour as a vehicle to contain the deepening hostility. NewLabour subsequently joined with three other capitalist parties to form the Alliance. In 2001 the Alliance, with Anderton as deputy prime minister in the Helen Clark-led Labour government, voted to send SAS troops to join the US invasion of Afghanistan. After its participation in this brutal and criminal war, the Alliance’s support collapsed and the party disintegrated.

Today, the anti-nuclear policy has effectively been brushed aside. Last November, for the first time in three decades, the National Party government, supported by the Labour and Green parties, welcomed the visit by a US naval destroyer to New Zealand. The protest group Greenpeace also cheered the visit, despite the continued refusal of the US to say whether its vessels are nuclear-armed. The entire political establishment wants a closer alliance with US militarism, precisely at the point where Washington’s encirclement and threats against China have raised the risk of war between nuclear-armed countries.