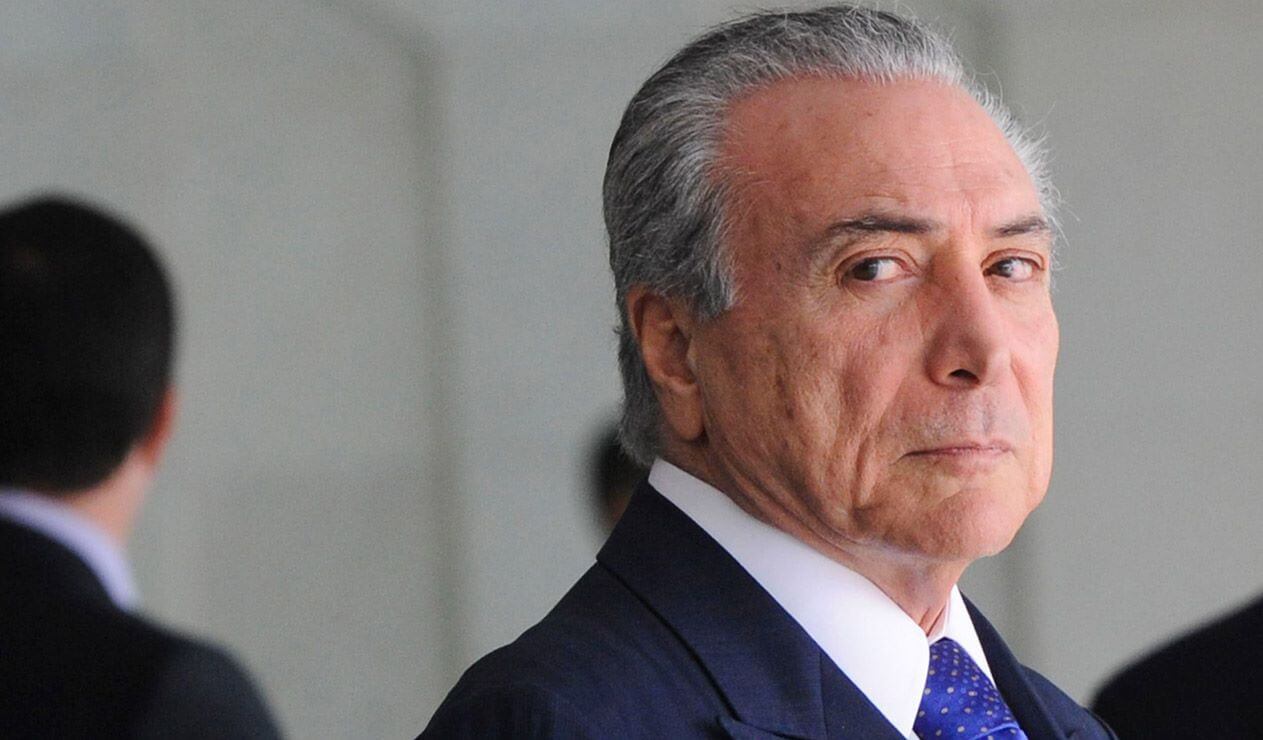

Interview with MST leader: “Temer’s government is the petit-bourgeoisie at the service of big capital”

By: Nicolas Allen / Source: Resumen Latinoamericano / The Dawn News / September 2016

We interviewed Joao Paulo Rodrigues, leader of the National Coordination of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST)

R.L.: Considering the continental offensive of the rights and the limitations of progressivist governments to carry out a radical social transformation, what role do social movements have nowadays?

We, the Brazilian working class are going through a very difficult moment, especially for the left. We’re coming from a period that we in Brazil call “the decline of political struggles”. Obviously, over the last three years the right managed to accumulate much more strength, because it made an important alliance with conservative sectors of the judicial power and of mass media and clearly managed to carry out great mobilizations with conservative sectors of the middle class and the far right against Dilma’s government, which was later overthrown. All of this weakened the left greatly over the last period. Beyond that, the last two years of Dilma were very difficult for the working class because there was a hard adjustment and a series of problems that drew historic sectors of the working class apart from the government.

There are 3 challenges ahead of us. The first one is to keep the left united because that unity allows us to resist the coup and make great mobilizations. Right now the Brazilian left is going through one of its best moments in history, with strong politicization, unity and struggle. The second task is to dialogue with the working class and get them to join the struggle. Because right now they are watching the events unfold on their TVs. They didn’t join the protests of the right nor of the left.

This task is very hard, because it entails fighting against a coupist government, and above of all to identify and create a new political perspective. And lastly, I believe that the left and popular movements have a great challenge ahead: Organizing a unified struggle platform, with political slogans in defense of democracy, but also in defense of rights, especially the Social Security Reform and everything pertaining labor rights which were an important conquest made by workers.

R.L.: Speaking of unity of the left, nowadays we can see many fronts of struggle being created, such as the Popular Brazil Front and the People Without Fear Front. Can you tell us more about the ideas of these fronts?

The People Without Fear Front is more of a struggle front, while the Popular Brazil Front is more politics-oriented. Both fronts were formed in the struggle against the coup. Now, the coup has been consummated. So we have to answer the question: what political slogans will fuel these fronts? The overall subject was already set with the “Out with Temer” and the calling to elections, so the challenge is which the political slogan will be.

Because you can’t discuss the goals only within the fronts, this has to include unions and other political groups. Fronts now have to work towards better organizing the grassroots, but above that, they have the great challenge of coming up with a political project for Brazil. We’ll see, in the next stage, whether our challenge was only about kicking Temer out, or our tactic will be to fight for better working conditions. The Popular Brazil Front is made up of over 60 political organizations, both rural and city-based, so in that sense it’s the most inclusive front. But it also has some limitations, which have to do with the ability of establishing political slogans that go beyond the “Out With Temer”.

R.L.: Is it true that organic groups of the PT [Workers’ Party, the party of Dilma Rousseff and Lula Da Silva] are part of the Popular Brazil Front?

Of course, the Workers’ Party is a part and there also is the PCdoB (Communist Party of Brazil), old sectors of the PSB (Brazilian Socialist Party), they are all in the Popular Brazil Front. Our concern is that the Popular Brasil Front doesn’t turn into an election front for “Lula 2018”. From this day on, we have many tasks to carry out. The Front also doesn’t intend to create a new party to replace the Workers’ Party. As a front, it has to go down two roads. The first one is struggle to show strength and to convene demonstrations and that sort of thing. The second task that the front has is to consolidate its own strength. It has to train militants and cadres, and it will have to dialogue with the people and establish a program. It has to build the political muscle to become a front that can truly make a difference. Something they have achieved in this sense was to build fronts with organizations of other countries of Latin America. But Brazil doesn’t have a lot of tradition in making fronts. We’re currently making the first experiment with fronts in the country.

R.L.: What is your take on the progressivist governments in Latin America over the last years, especially regarding the so-called neo-developmentalist model as a political-economical model?

Lula’s government, along with Dilma’s government, inaugurated neo-developmentalism in Brazil, which was really a combination of three classic elements. The first one is state investment in cooperation with big capital, which means ties to all traditional forms of investment in Brazil financed by big banks. The second element is the idea of class conciliation, an alliance between the classes, which Lula was very clear about. And the third element is social programs to combat poverty.

We believe that this project has reached its ceiling for two reasons. Firstly, because Brazil doesn’t have the capital nor the resources to finance social programs without making very profound reform. And secondly, because the current juncture has so many contradictions that a class conciliation is almost impossible in the medium-term.

Nowadays, the situation is completely different: the conflicts between the bourgeoisie and the working class are out in the open. Therefore, we think that the idea of neo-developmentalism is very limited. The next stage will have to be a popular project that can create a new political, economic and social perspective. This project has not been outlined yet in Brazil, and it could be called “popular and democratic”, which means it could be a project with elements that aim towards democratizing the state, of course, but above all it must firmly make reforms, such as the agrarian reform, the urban reform, reforms in health and education, etc. These reforms must be profound, or else Brazil will continue to be a country that combats poverty in a context of great social inequality.