Second of three articles. Read first article here

When money keep silent, the liberal democracy is gasping:The EU in East Europe and the Black Sea region after the fall of communism

By Radu Toma

Czech Republic

After the ‘Velvet Revolution’ of November 1989 and the removal of the communist leadership, the opposition to the new ‘invader’, economic liberalism, and suspicions generated by the EU, had old roots in the Czech Republic. The Euroscepticism manifesto, from the beginning of the 1990s, of the former prime minister Vaclav Klaus (1992-98), president of the country in the years 2003-2013 is well known. His position and moral arguments were the priority of developing the national capital ahead of the foreign one, even with sacrificing a greater efficiency of the market and even of Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). A vigorous defence of the Czech national state, he said, is a guarantee of national identity, against the supranational institutions recommended by the EU and the neoliberalism (IMF, World Bank). And it must be made clear that, from the beginning until now, neither neoliberalism, nor the EU nor NATO have managed to have their way in the Czech Republic. The last Czech Prime Minister, Andrej Babis, who was appointed by the President on December 6, 2017, as the head of the government, spoke in harsh words, rejected the agenda of the globalist elites; he swore that he would leave the ‘corrupt EU’, destroy globalism and the new world order and ‘restore the sovereignty of Eastern Europe’ (30). In the end, after qualifying the economic sanctions imposed on Moscow by the West in 2014 as ‘meaningless’, as did presidents Klaus and Zeman, Babis ruled for the further development of his country’s economic relations with the entire Eurasian space, including Russia (31), as a solution from recent past that had contributed to lessening the effects of the 2007-2008 crisis and as a future one, for the economic freedom of movement of his country.

*

From Vaclav Klaus, Prime Minister and President from 1992 to 2013, Milos Zeman who has succeeded him until today, and the last PM Andrej Babis from 2017 onwards, in Czech Republic’s case we can talk of a continuity in promoting the political and economic national interest, with assumed sacrifices, in front of the unopposed offensive of Western neo-colonialism, camouflaged in economic neoliberalism and free market democracy. With popular support and being strongly supported, for over 25 years, by the Czech public opinion, the three rejected offers coming from the Euro-Atlantic world which were considered inappropriate for their country, from sending soldiers to Iraq in 2003 and setting-up missiles, or US military bases on their territory, up to the refusal, after 2015, to accept Islamic migrants. The Euroscepticism was a social and political phenomenon manifesto even before the accession of 2004 and still exists today in acute forms, at the limit of Czexit.

It is clear that, far from happening out of love, the accession of the Czech Republic to the European Union was a marriage of interest.

Vaclav Klaus’ euroskepticism in the 1990s was more than a leader of a post-communist country’s precaution against neoliberalism (32). The Czech privatization with vouchers sought the support of the national capital against the foreign one. A stronger protection of the Czech state was sought and ensured, as the guarantor of national identity and political autonomy before the supranational institutions fabricated and promoted by the EU and considered by the Czechs as inefficient, undemocratic and lacking political, historical and cultural legitimacy in their country (33). It is an European Union, Prague said, which sees Eastern Europe, including the Czech Republic, as a source of rapid and great benefits, of raw materials, cheap, skilled labour, and a possible buffer zone against political and security risks coming from Eurasia, the Balkans and the Black Sea.

The Czechs’ resistance to the neo-colonialist expansion of the West went to paradoxical, extreme forms, but perfectly democratic ones. After the December 2017 elections, when he won with only 29% of votes 78 of the 200 parliamentary seats, in July 2018, Babis brought back the communists to governing (34), an absolute premiere throughout Eastern Europe after 1989. It was an absolute premiere, but which proved that the Czechs have the gutts and the clairvoyance to revive even the political arguments of the past, of course, the valid ones, when they question and reject another external, severe hegemony, this time coming from the West. We should immediately point out that the PM’s choice was not accidental: although he never did penances for the past four decades of authoritarian rule, polls have shown since 2012 that, in the population’s preferences, the communist party was the second political party in Czech Republic, with over 20% of the expressed opinions. The reason? They opposed the European Union, put the economic crisis on the incurable defects of capitalism, older or newer, and presented themselves as the oldest and most serious truly reformist party in the country, even before 1989 and the fall of communism (35).

Meanwhile, in Czech Republic, liberal democracy has been for years in recession, almost half of those who surveyed thinking it is not the best form of governing for their country. Also, there, Viktor Orbán’s illiberal democracy and authoritarianism are on the rise, the closure of Soros’ Central European University in Budapest, in the spring of 2017, was ignored by politicians, media and the public (36). The almost sole protester was Jiri Drahos, defeated in the last presidential elections, in January 2018, by Zeman. Instead, Orbán of Hungary was publicly praised by former President Vaclav Klaus, who had rejected Soros’ initial offers to build the mentioned university in Prague in 1990.

In 2018, experts from Bertelsmann Stiftung, a German independent foundation for the promotion of democracy, confirmed that democracy is declining in many industrialized states in the European Union and elsewhere, that political reform is becoming more difficult and the quality of governance is declining (37). The United States, Hungary, Poland, Turkey and Mexico are the first of the 26 countries listed. The study shows an increase in the population’s confidence in illiberal or authoritarian governments such as Hungarian, Polish and Turkish governments, who, it is mentioned that, rather than governing, are in a permanent political campaign (38). And the Czech Republic and Iceland, the Bertelsmann Stiftung says, are also aligning to this political trend, both having performed poorly in recent years in terms of democratic standards.

Western specialists, scholars and authors, as well as from the Czech Republic, have spoken and written in recent years about the general recession in front of the uncontrollable economic failures and the populism’s offensive in Europe (39). This fact led the well-known British journalist, historian and writer Timothy Garton Ash to recently publish the free essay ‘Is Europe disintegrating?’ (40). It is a captivating story about a guy cryogenically frozen in 2005, in the time of the glorious and peaceful colour revolutions in Ukraine, and brought back to life in 2017 when, he said, ‘I was going to die again due to the shock.’ Crisis and disintegration ruled everywhere, the eurozone wasn’t working, sunny Athens was living in misery, Spanish doctors had left to waiter in London and Berlin, the children of Portugal were looking for work in the former colonies of their ancestors, Brazil and Angola, Europe still had no Constitution, east – Europeans were about to use the British Brexit brand for theirs Polexit, Czexit, Slexit, Hunexit, Roexit and Bulexit, the British were getting ready to lose in 2019 the European citizenship acquired in 1989; border controls had been restored between Schengeners and the others, of course ‘temporarily’, and Ukraine was left without Crimea, and de facto lost its industrial East. What are the motives invoked by Garton Ash, of this unfortunate resurrection in a miserable world? Neoliberalism as a blind belief in the virtues of the market, irrational reliance on its organizers, contempt for the state as a participant in the nation’s socio-economic life, unconditional application of the economic dogmas of the ‘Washington Consensus’ (41), marginalization of entire countries (Polska B, i.e. second hand Poland), insulting those from the south of the continent – PIGS, acronym for Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain – social dislocation, revolting inequality and extreme poverty in Eastern Europe, all these, says the same author, are consequences of liberalization, markets deregulation and out of any control privatization. From London and Timothy Garton Ash, welcome to Ukraine, Georgia and others eager to join the EU!

Why has the Czech Republic become a controversial political subject for policy makers and experts in international relations in the West? The shortest answer to this question is: because of its seemingly duplicitous behaviour in political relations with the West, and with Russia.

So, in January 2018, the re-election of Milos Zeman as Czech President was seen by most of the aforementioned Westerners as a sign that this country will further strengthen ties with Russia and China, and they all asked themselves, if maybe the Czechs would also start on the path to separate from the EU. The leaders of the two Eurasian powers were among the first to congratulate him, Vladimir Putin praised his ‘authority’, and Xi Jiping underlined the ‘strategic partnership between China and the Czech Republic’. A Zeman who, in the fall of 2017, said in the middle of the European Parliament, that sanctions against Russia were ‘damaging and inefficient’ and that Crimea’s return to Russia was a ‘closed matter’. An overlooked Zeman – everyone knew that the Czech president is rather a decorative figure, without much executive power. But things are not as they seem with him, the guy has his own foreign policy, a personal one. He travels often to China and on a regular basis to Russia and is always surrounded by businessmen, industrialists and, almost every time, has contributed to the signing of important contracts. In the years to come, experts believe, the president will try to place several, strategic, multi-billion-euro contracts, such as with the Russians to expand the Czech nuclear power station in Dukovany. And so, those experts are adding, Czech Republic’s tendency to distance themselves more and more from their Western partners will continue.

Apparently, a correction to the president’s appetite for the Eurasian space could come from PM Andrej Babis, but it is not clear if he can or wants to change things. The leader of the ANO governing right-wing party, owns a $ 3.4 billion empire and does business almost everywhere in Europe, including Germany, being partially, and for a long time, subsidized also by the EU, which would lead to the idea that the Czech billionaire is interested in having good relations with Brussels. But, like Zeman, he has repeatedly said that EU economic sanctions against Russia are a mistake. At a recent high-level meeting in Budapest, he joined Viktor Orbán’s anti-EU rhetoric, compared the European Commission with a communist ‘Politburo’ from Kremlin, in the former Soviet Union, and after a few days, in Brussels, changed his mind and promised a more active role of the Czech Republic in the EU. He immediately changed his mind again and rejected any recommendation regarding the welcoming of Islamic migrants in his country. Although the collaboration between Zeman and Babis is older and well-known, the misunderstanding between them regarding a referendum organization on the remaining of the Czech Republic in the European Union is equally prominent to all. Zeman wants to consult the population and Babis firmly opposes a possible Czexit, realizing, probably, that everything could turn into a nightmare for his mega economic status.

At present, the ambiguity at the highest level of the Czech policy towards the West and Russia makes history. Symbolic in this sense was Zeman’s recent absence from the official commemoration of 50 years since the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the same Zeman who was among the leading leaders of the ‘Prague Spring’ and the fight against foreign occupation from half a century ago. Criticisms towards him flow unabated in the West. Presidential Prague is a ‘centre of Russian espionage and propaganda operations’ for all of Eastern Europe, and beyond. Zeman is considered arrogant, contemptuous of journalists and intellectuals, a ‘Trump-style’ ill-mannered, a supporter of the war on terror against the West and a foul-mouthed like the British Nigel Farage. He is indecent, vain, a Russian-Chinese tool, disrespectful to the ‘liberal elites’ (42), his victory in the January 2018 presidential elections undermines the unity of Europe and it is to Putin’s liking.

Things can be seen differently. Milos Zeman continues the tradition of his predecessors, Czech Republic presidents Tomas Masaryk, Edvard Benes, Ludvik Svoboda and the general secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, Alexander Dubcek. Zeman, the last one on this list, certainly wants for his country something not done yet, nowhere: a ‘globalism with a human face’.

*

From November 17, to December 29, 1989, the Velvet Revolution changed almost everything: the one-party state disappeared, the Iron Curtain on the borders with West Germany and Austria was demolished. Husak, detested, left in disgrace, Dubcek, dusty, returned to triumph, a parliamentary republic began to function, a former dissident, Vaclav Havel, became the president of the free country on December 29. Almost everything has changed, but while one political regime was replaced by another, the former Czechoslovakia’s strong economic ties with partners in the former communist world have been preserved. After 1990, the country remained the ‘bridgehead’ of the Russian metallurgical industry to the west of Europe and the EU (Celiabinsk Pipe and UGMK, from Urali). Since the time of CAER, Russian companies have owned, and continued, even in the 1990s., to own important parts of the Czech steel mills and the Skoda industrial equipment factory. Farmatec Czech Republic further built high-productivity model farms throughout Russia. The central and regional chambers of commerce of the two countries (170 of them) exchanged 24/7 information through their own network, etc.

The Czechs and Russians, Slavic and other, have gotten along good throughout history, have lived in harmony for hundreds of years. In the 19th century, the century of national rebirth throughout Europe, and of the uprising Pan-Slavism, Russians were always described as the last defenders of the Slavs oppressed by the Germans, Austrians and Turks, and Russia was considered by many Czechs, seeking self-determination, as their natural ally, as a possible ‘saviour’ from under the Habsburgs. Then, the communism years created strong economic links, but the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 put an end to the good relations between the two partner nations. On the walls of Prague the Russian soldiers, perched on tanks, could read the words: ‘We waited for you for six years in the World War II to come here and free us, what you did now we will not forget in a hundred years.’ 1968 was a serious blow to the Czech-Russian relations, but not a fatal one, and the hundred years of unforgiveness was shorter. Much shorter. The old anti-Russian stereotypes, including 1968, have softened, the new euro-communitarian Czech had other approaches and horizons. In the spring of 2010, in Karlovy Vary, a reporter from the New York Times (43) interviewed two people, a former Czech dissident from the Communist years, and a very young Russian businessman established there. The first one said: ‘I didn’t expect the memory of 1968 to last so long. The world has changed since then. We, the Czechs, no longer have to assume that whenever they defend their interests, Russia is an aggressor.’ Then, the 21-year-old Russian from Urali said: ‘I got tired of being accused of things that happened before I was born.’ In the same excellent report of ‘NYT’, an American official from President Obama’s team, at the signing in Prague, with Russian President Medvedev, of the US-Russia Agreement to Reduce the Nuclear Arsenal (New Start Agreement) said: ‘President Obama aims to create a new attitude of the regional leaders, in which the older fears of Russians hiding under the beds of Eastern Europeans remain only ghosts of the past.’

Ukraine and Georgia, riparian to the Black Sea, have a lot to learn from the Czech Republic when it comes to three things: (1) relations with the European Union, (2) relations with NATO and (3) relations with Russia. When they will know this lesson well, they will be much, much wiser.

Slovakia

Located exactly in the middle of Europe, a country as large as the Republic of Moldova and with 5.47 million inhabitants, in 2017 Slovakia had a GDP of $ 96 billion, not far from Ukraine’s, of 110 billion, but with a population of over eight times smaller (!), and six and a half times larger than Georgia’s (15 billion) with an almost equal numbers of inhabitants, the latter two riparian to the Black Sea and contender to the accession to the EU and NATO (44). After the communism fall, Slovakia did all the ‘homework’ received from the West. It became a member of the OSCE, the OECD (February 1994), the World Trade Organization (WTO, on January 1, 1995), NATO, the European Union and the Schengen area (May 1, 2004), was the first of the Visegrad group (V-4) in the Eurozone, on January 1, 2009. It is a small Eastern European country, with soldiers in UN, EU and NATO missions in Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, Cyprus, Somalia, etc.; with the world’s largest production of cars per capita (45). They are making VW, Porsche Cayenne and Lamborghini Urus models, Peugeot and Kia, and have produced 1.04 million pieces in 2016. The British Land Rover Discovery has been recently added to the list. It is a country with a modern, European economy and society (the US State Department has been saying it since August 2007), but with socialist economic policies (a November 2008 analysis of the Federal Institute for Technologies, in Zurich, Switzerland); with complete free healthcare, and also free education, and with the longest post-natal period in the European Union, with the largest population of ‘peasants’ in Europe – 45% of Slovaks live in villages with less than 5000 inhabitants, 14% in small villages and hamlets under 1000 souls, finally, with peasants traveling without a visa in the United States and 178 other countries and territories in the world (46).

Due to all the above and more, Slovakia was considered ‘one of Europe’s most impressive success stories’, according to BBC Monitoring – Country Profile Papers, on January 8, 2013. However, after another year from this vibrant praise to their country by Westerners, in 2014, in the last elections for the European Parliament, only one of eight Slovaks, ie 13.05% of them, voted – it was the record absenteeism in the entire history of the EU. Now, after almost four years, Bratislava’s relations with Brussels are ‘politically correct’ (what a monument of hypocrisy is this neoliberal expression!), and cold. Do Slovaks care so little about the future of the EU?

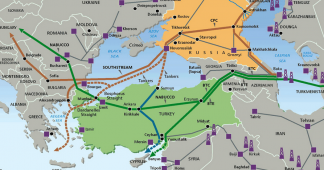

Simultaneously with the opening to the West at all levels: political, economic, cultural, free movement and the search for opportunities, etc. it is extraordinary that in Slovakia the Russophobia did not exist as a prevalent phenomenon neither before nor after the collapse of communism, detested by Slovaks as well as by all the other Eastern Europeans. After 1990, Russia remained a major economic partner of Bratislava, starting from the time of the CAER – organization in the late 1940s-’90s, of economic cooperation between the Eastern-European socialist countries and the former Soviet Union – the parties further developed a profitable collaboration on third markets, in Asia and in Arab countries. At the end of the 1990s the Slovak-Russia intergovernmental commission for economic and technical-scientific cooperation was founded, and joint industrial projects were launched in both countries. And at the end of 2001, Slovak President Rudolf Schuster, a Russophile, but with a pro-Western government, officially travelled to Moscow, accompanied by a large delegation of ministers and experts from economy, commerce, industries and technologies, etc. and businessmen. On arrival he stated that his visit ‘will melt down the last traces of ice from the Slovak-Russian bilateral relations of the past years.’ The Slovak-Russian economic relations expanded long after 2006, in 2008 Slovak exports to Russia increased by 84% over the previous year, maintaining an upward dynamic throughout the years of global crisis and recession. From $ 405 million in 2004, they reached nearly to $ 3 billion in 2012, at that time almost two and a half times larger than Romania’s exports in the Russian Federation, at a population four times smaller (?!). At their meeting in Moscow, on December 12, 2012, Foreign Ministers Lavrov, of Russia, and Lajcak of Slovakia, discussed joint economic projects. It was announced that Russia will launch, in Slovakia, a hydroelectric power plant construction program and that joint projects for high technologies are being prepared. In March 2013, at the 16th session of the Slovak-Russian intergovernmental commission above mentioned, was announced that Russia has become a major trading partner of Slovakia, with a total trade of $ 10 billion. But the economic embargo imposed on Russia by the EU after the 2014 Crimean crisis – a embargo that Bratislava always disapproved and considered harmful to both parties – has led to a reduction of bilateral trade by more than half (47). They continued and recovered to a good extent in the following years, in 2017 Russian-Slovak bilateral trade reached $ 5.3 billion (48). In the end, after previous negotiations with the Russian company Rosatom, in October 2018 the Russian Minister of Industries and Trade announced the possible participation of Russia in extending the existing facilities at the Mochovce and Bohunice nuclear plants, in the west of the country, and building two new reactors with an installed capacity of 2,400 megawatts; he also provided cooperation in the field of nuclear energy on third markets (49).

In 2010 Ivan Gasparovic, President of Slovakia for a decade, said: ‘Russia and Slovakia have special connections, which go far back in history. I think we should maintain this Slavic unity, our historical heritage … We are members of a Union (EU), we must have our own proposal regarding an anti-missile defence system in this region … the US is welcomed in a European defence system and I believe, and not only me, that Russia must be part of it’ (50).

After joining the EU in May 2004, Slovakia was classified as a European country in the Moscow’s ‘pragmatic friends’ group.

*

Three successive governing periods, each stretching for about eight years, two social-democratic ones and one neoliberal, created the unique political profile of Slovakia, in a doctrinally, economically, militarily divided Europe, with two distinct geopolitical delimited spaces, the West and the East.

The first was of Vladimir Meciar, prime minister between 1990 and 1998. Former secretary of the communist party and political VIP in the last regime, opponent of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, ousted from the party and declared ‘enemy of the socialist regime’ was elected prime minister in June 1990 at the recommendation of Alexander Dubcek, the reformer of 1968. Then, he was harshly criticized in the West for his autocratic style of administration, disrespect for democracy, persecution and manipulation of the media, corruption, obstruction of the strategic enterprises, of national interest, privatization, etc. It was also said that, under his rule, Slovakia was partially isolated from Europe, and negotiations with NATO and the EU were delayed.

And, 15 years after his departure, West’s views on Meciar seem to have changed radically. A recent re-analysis of the macroeconomic data revealed notable achievements, prolonged years of economic growth, low levels of inflation and unemployment, and it was also stated that, by rejecting the economic ‘shock therapy’, slowing down privatization, preserving the country’s key industries and population’s social security, Meciar was able to alleviate the negative effects of 1990s’ transition and prepare the field for the subsequent market reforms (51).

Under Meciar, the transition to capitalism was done slower, without dangerous social waves, Slovakia recorded the best economic performance – GDP, labour use, control of inflationary forces, etc. – from Eastern Europe (52). He refused to privatize the basic industries, chemical, metallurgical and arms, kept most of the banks for the country and for these ‘reprehensible’ facts he was criticized every way possible by the Western neo-colonialism’s exegetes out to loot in the East. (53). To a balanced extent, Meciar’s governing supported the privatization and reform of the market. In 1996 private enterprises provided 79% of GDP, and by the end of 1997 only 3% of them had remained in public ownership (54).

Immediately after the fall of communism, in the years 1990-91, the Slovak population vigorously opposed the drastic economic reforms. The social inequalities which appeared almost abruptly to the neighbours, the Czechs, contributed considerably to the ‘velvet divorce’, without a popular referendum, between the Czech Republic and Slovakia, in December 31, 1992. In 1992, Meciar understood that he is the leader of a state whose citizens feared the ‘shock therapies’ that have soundly shocked the East, Poland, the Czech Republic, Russia etc. that is, by the prescriptions of an unopposed capitalism, he understood he could not afford unlimited unemployment, or a collapse of the standard of living, and did everything for this not to happen. He revitalized the heavy industries, limited the price of food, encouraged the national banks and the population’s savings. He held to the end his ground regarding economic nationalism and, thus, consolidated the governing, preparing it for the next free market reforms.

In 1998, the governing of Vladimir Meciar ended. He received endless criticism, such as suppressing the free media, intimidating political opponents, corruption, bureaucracy, etc. but Slovakia’s rising today would not have been possible without his policies. The existence of a strong heavy industry from communism time, of a conservative population, the lack of democratic institutions, all of them required economic policies and a slower transition to privatization and the free market.

In 1998, Mikulas Dzurinda’s government came, so to speak, to the ‘set table’ by the former and much vilified, at that time, Vladimir Meciar’s government. He came to a consolidated democracy. He quickly launched a series of reforms to complement previous privatizations, and massively cancelled government spending. The shock was finally felt by all, domestic demand decreased, social assistance programs evaporated, unemployment reached unknown levels in the past, 20% in 2001. Nevertheless, the Western public relations machine (PR) worked flawlessly, in 2002 Dzurinda obtained a new mandate, in 2004 Slovakia entered the European Union, the PM thus reaped the fruits of economic stability built, for the most part, by the previous government.

Furthermore, between 2002 and 2006 the Dzurinda government stood out for adopting a series of neoliberal reforms aimed, first and foremost, at delegitimizing some institutions of the past decades which were in the service of social solidarity. The decrease of social spending has not been as drastic, say, as in Estonia, and kind of ‘social-liberal’ capitalism was reached, that is, an artificial merge between social protection and the free market forces (55). A simple, flat tax of 19% was introduced, pensions were reformed on a three-pillar system, with an increased risk for taxpayers, social assistance diminished, was poorly administered and devastated by corruption, health insurance passed from the state, to private corporations, to the common medical treatments was introduced a co-payment system between insurance company and patient, the population’s discontent generalised. In terms of education, the reforms sought to transfer the responsibility for higher education from the state to students and their families, and their failure caused a real national scandal, the Minister of Finance, Ivan Miklos, Dzurinda’s associate, became the most detested person in the country. In Justice, the reform followed several American models, including harsher penalties and longer periods of incarceration, to limit the more frequent antisocial actions in a more permissive and individualistic society, but also in this area the neoliberal experiment of the Justice Minister, Daniel Lipsic proved to be of no effect for the traditional norms of morality and social cohesion in Slovakia. In general, ‘the import’ of Western reformist ideas and measures of Dzurinda’s team, as well as of arguments for globalization, did not find a favourable ground in a tribal Slovakia. With all of Meciar’s resounding defeat in 1998, Slovakia’s entry in NATO and EU, the instauration of market democracy, etc. Slovakian ‘meciarism’ and illiberal democracy at the forefront of the 1990s will prove to be more vigorous realities, than the later neoliberalism of Dzurinda & Co., in a country with populist inclinations.

What happened after 2006 proved that neoliberalism did not find in Slovakia as fertile ground as in other parts of the West. It did not bring a comprehensive, definitive change, but only an adjustment, an adaptation to the new conditions imposed by the accession to the European Union. Neoliberalism came there with the new capitalist economy, but it did not become the ideology of that country, as it didn’t for any other Eastern country. The government of Robert Fico, after Dzurinda, from 2006 to 2018, put a definitive stop to neoliberalism in Slovakia and ruled for the return and reign of social democracy in that country.

A radical change of direction in Slovakia’s domestic as well as international policy occurred in 2006 and, with a nearly two-year interruption (July 2010-April 2012), continued until 2018, under Robert Fico’s two governments. Nicknamed in the West the ‘alpha male’ of Slovakian politics, Chavez, or Putin of Slovakia, he led a coalition of his social-democratic party, with the far-right Slovak National Party, of the ultra-nationalist Jan Slota and the People’s Party, of the former PM Meciar. In 2006, to him and his coalition were foretold a short-lived political life, but he remained in power for more than seven years. In 2007-2010, before the global recession, Slovakia had the highest average economic growth in the EU of 6.5 %. His social and economic policies were focused on disadvantaged social groups and the rising of the poorer regions of the country; he abolished population co-payments to health insurance and cancelled some privatizations of some national strategic interest companies, and he even renationalised companies privatized by the previous government. He demolished the neoliberal pension reform, of the former government, the second pillar was greatly reduced, the third abolished, in order to protect the social system from the plundering private businessmen. In the same way he dealt with the health system, the medical insurance returned exclusively in the state’s care, he was determined to go up to nationalisation, to get rid of the private parasite-companies (56).

In 2012, immediately after winning the second term, Fico introduced a new ‘Labour Code’, more favourable to employees with permanent employment contracts. A lower VAT of only 10% was established for drugs and books, and private insurance companies have been practically removed from the market. He disciplined the large French and German public utilities companies which entered the Slovak market, threatening them with nationalization (57). He completely renounced the ‘savage’ Nord-American type, neo-liberal capitalism of the former Prime Minister Dzurinda and aligned Slovakia among the social, welfare, western European states.

He also has forgotten the foreign policy of the former government, from the first moments after his installation as prime minister he distanced himself from the Bush Jr. administration and his anti-Russian policy in Eastern Europe. In 2006 he withdrew 99 of the 110 Slovak military from Iraq, the last 11 returning in 2007. The Slovak-US bilateral relations have cooled down. In other regional and international issues, Fico rejected the US anti-missile shield project from the East and the construction of US military bases equipped with missiles and radars in the neighbouring Czech Republic and Poland (58). Fico refused to recognize Kosovo’s independence and considered it a ‘big mistake’ (59). He also did not criticize Moscow for its policy in the former Soviet space. Without being provocative or zealous, he promoted a rapprochement with Russia and Serbia, thus ending an old foreign policy of Bratislava since 1998, when Slovakia aligned itself with NATO and the West (60). In fact, after his accession to governing in 2006, the new Slovak prime minister stated that relations with Russia will improve, ‘after eight years of deliberate neglect’; he also refused to buy fighter jets from the West, modernizing the Russian old equipment (61). In the 2008’s Russian-Georgian war, he accused Georgia of provoking Russia when they attacked South Ossetia (62). He made no comment in 2014, when Crimea re-joined Russia, but said on several occasions that the EU’s economic sanctions against Moscow are ‘meaningless’ and a threat to Slovakia’s economy.

And Slovakia has vigorously rejected Brussels’s outrageous xenophobia accusations, as well as the plans of the European Commission and Angela Merkel, to apply a new, last-minute ‘shock therapy’ to East Europeans, to force them to receive illegal migrants from The Middle East and Africa. Fico said: ‘As long as I am prime minister, mandatory migrant quotas will not apply in Slovakia’ (63).

Robert Fico has constantly clashed with the press, accusing it of being unable to ‘support ordinary people’. The exchange of replicas between the PM and the media has often turned hot red but, most importantly, the prime minister has enjoyed the confidence of the governed, its internal and external performance was supported by the vast majority of Slovaks. He gave Slovakia almost eight years of stability and development, brought it to Europe through the front door, with their head held high.

March 22, 2018, Robert Fico resigned following the crisis caused by the murder of a Slovak journalist, who was investigating the activities of the Italian Mafia in Slovakia. Deputy Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini, from the same social-democrat party, SMER, became the Prime Minister of the country. In Bratislava they said that he will continue the same national policies as his predecessor. So far, it has been announced that Slovakia will not extradite Russian diplomats because of the Skripal case in the UK (64) and that, standing with the United States, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Australia, Austria and Israel, will not sign and ‘will not in any way support’ the UN Agreement on Migration in Europe (65).

*

The political performance of Slovakia, the country between East and West in the geographical centre of Europe, could provide optimal solutions for Europeans with identity problems: a drifting EU, a Germany probably at the end of another missed hegemony in the last hundred years, without future plans; a Ukrainian and a Georgia from the Black Sea, contenders to the West, but with the lesson about the West not learned; a France with a pathetic president left in search of lost grandeur, a Romania without national leaders after 100 years of national state, etc. (to be continued)