By Lasanda Kurukulasuriya

The recent visit to Sri Lanka by Japan’s Foreign Minister Taro Kono saw governmental confirmation of Sri Lanka’s first Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) project. A statement from Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe’s office revealed that an MoU with Japan to build a Floating Storage Regasification Unit (FSRU) would be signed in the third week of January. The project to build the FSRU and LNG terminal will be a joint venture by Sri Lanka Ports Authority with both Japan and India.

Japan’s public broadcaster NHK described Kono’s visit as being “part of Japanese government’s plan to promote cooperation for port expansion projects.” Kono’s low profile trip concluded with a tour of Colombo port. Japanese media did not hesitate to report the port visit in the context of Japan’s concerns over China’s growing maritime footprint in the region. “China is increasing involvement in port development in Sri Lanka” reported NHK World, adding that “Before the port visit, Kono told reporters that projects to build ports and other infrastructure should be open to any country.” Kono’s remark flagged Japan’s concerns over China’s major role in Sri Lanka’s infrastructure development, and particularly the Chinese-built Hambantota port in the South. His Sri Lanka visit was part of a tour that included Pakistan and the Maldives – both states in which China has significant infrastructure investments under its ‘Belt and Road’ initiative.

LNG is very new to Sri Lanka as an energy source. What makes LNG different from any other type of power project is that an LNG terminal would include docking facilities within a port, for the special tankers carrying liquefied gas. As a result, the strategic dimension of investment in a LNG terminal or FSRU by any foreign partner cannot be ignored. It is in effect an investment in port development. Sri Lanka’s LNG terminal is to be located within the Colombo port – one of the busiest ports in South Asia and an important trans-shipment hub in the Indian Ocean.

Once Sri Lanka’s LNG terminal/ FSRU infrastructure is in place and becomes operational, pipelines from Colombo port will transport the gas to two dual-fuel power plants in Kerawalapitiya, 12 km north of Colombo, which are due to be completed around 2021 according to Dr Suren Batagoda, Secretary to the Ministry of Power and Energy. One will be built in partnership with the Japanese government and the other in partnership with government of India he said.

Japan’s concept is “to develop free and open maritime order in the Indo Pacific region as an international public good,” said Toshihide Ando, Deputy Press Secretary of Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs at a media briefing with a group of local journalists in Colombo. “It is important that we have maritime cooperation in this region” he said. Japan has indicated interest in the development of Trincomalee, Sri Lanka’s natural deep water port on the East coast, at various times. Asked about the status of talks in this regard, he declined to comment.

The increasingly anxious interest shown by Japan and India in investing in the development of Colombo and Trincomalee ports, is related to concerns arising from Sri Lanka’s recently finalised lease of Hambantota port to a Chinese company that holds a majority stake. The apparent loss of sovereign control over the port, strategically located near major East-West sea lanes, has led to fears that it may become a Chinese military base, in spite of Sri Lanka’s assurances to the contrary. “We want to ensure that we develop all our ports, and all these ports are used for commercial activity, transparent activity, and will not be available to anyone for any military activity,” Prime Minister Wickremesinghe was reported as saying in Tokyo last April.

As an island nation with scarce natural resources, Japan depends on maritime transport to obtain most of its requirements including energy, hence its concerns over access to sea lanes. Japan’s interests now converge with those of the US and India, and with China being seen as a common adversary, a closer strategic partnership has evolved among the three. Japan now participates in the Malabar naval drills with US and India, and uses US-type rhetoric with terminology like ‘Indo-Pacific’ to refer to the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, blurring the boundaries.

Historically, Japan’s relations with Sri Lanka have been cordial. Japan has always been generous with aid and is also a major development partner. During Sri Lanka’s war years Japan was one of the four co-chairs of the peace process, and when the Western co-chairs threatened to cut off aid Japan reassured Sri Lanka that it would not follow suit. Japanese envoys never fail to recall the speech made by Sri Lanka’s former president J R Jayewardena at the San Francisco peace conference in 1951, where Sri Lanka came to Japan’s defence. Then Finance Minister Jayewardena quoted the words of the Buddha saying “hatred ceases not by hatred but by love,” and asked that no reparations be exacted that would harm Japan’s economy. “The Japanese still remember that this speech supported Japan’s return to the international society after the WWII,” the visiting foreign minister said in a written interview with the state-run Daily News ahead of his visit. One could say Sri Lanka’s relationship with Japan has been somewhat special.

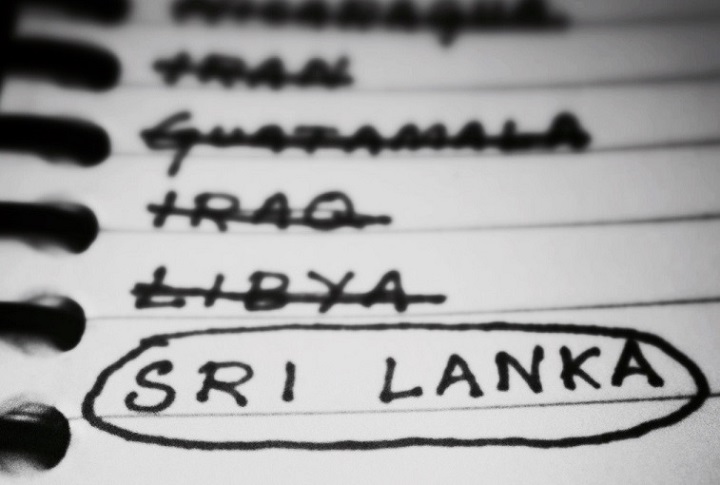

Against this backdrop Japan’s interest in investing in Sri Lankan ports would normally be seen as a welcome development. But with India a partner in the proposed joint venture, and given the evolving strategic landscape, it would now appear to be embedded in a larger trilateral project of countering Chinese influence. This could mean there is a hidden cost – in that Sri Lanka risks being unnecessarily drawn into a big power conflict in the event of an escalation in tensions between China and the US and/or India.

Analysts tracking Japan’s role in shaping the regional security architecture acknowledge its more robust and independent policies, but also express misgivings. “The only question is how Japan will decide to utilize their naval power in the coming decades,” wrote Brian Kalan in a military analysis for Southfront two years ago. “Will it be used in the pursuit of ensuring their independence and peaceful relations with their regional partners, or in the self-destructive pursuit of U.S. hegemony in the region?”