By Edward G. Stafford

Jul 08 2020

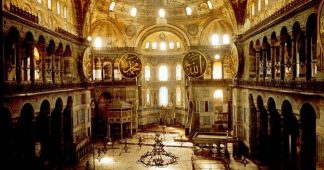

The Council of State, Turkey’s highest administrative court, is currently considering whether to reconvert the Hagia Sophia museum into a mosque, a status it held from the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 until 1931, the year in which Mustafa Kemal Atatürk closed it pending its re-opening in 1935 as a museum.

How will the decision affect U.S.-Turkey relations? Not greatly. Why not?

In a July 1 statement, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made clear that the United States would prefer that the Hagia Sophia remains a museum. The statement also noted that Turkey had administered the Hagia Sophia “in an outstanding manner for nearly a century”.

These are hardly the words of condemnation nor does it contain even a subtle threat of consequences. No, the statement indicates that if the Council of State rules that the Hagia Sophia becomes a mosque again, the U.S. will be disappointed, but that will be about as far as it goes.

There are several reasons for this.

First, while the statement emphasises the UNESCO World Heritage status of the museum and its capacity as such to serve as a bridge between peoples of “differing faith traditions and culture”, it implies that the decision of its status rests firmly with the Turkish government.

It focuses on the prestige Turkey has garnered in its administration of the site and heaps accolades on Turkey for the way it has managed its patrimony. It is the plea of a concerned friend, not the scolding of a nosey neighbour.

Second, though many Christians attach great importance to the Byzantine-era Hagia Sophia as the former greatest church in the Christian world, most of President Trump’s Evangelical Christians do not.

While some Evangelical Christians would lament Hagia Sophia becoming a mosque again as further evidence of the attempts of Islamists to snuff out Christianity in the greater Middle East, many if not most U.S. Evangelicals reserve their political efforts for the protection of access to Christian sites in Israel and Palestine.

And, although Christian tour group itineraries in Turkey usually include a visit to the Hagia Sophia, sites in Cappadocia, Ephesus, and elsewhere in western Turkey take precedence for most U.S. Christian tourists over visits to current or former churches in Istanbul.

Third, the status of the Hagia Sophia matters much more to the Russian Orthodox Church, and Russian President Vladimir Putin, than it does to Trump. From the U.S. perspective, it is better for the Russians to offend the Turkish government by interfering in a decision about a former church connected to an Orthodox branch of Christianity that is quite small in the United States but is dominant in Russia.

Finally, Trump can rest assured that few, if any, Democratic Party voices in congress or the media will rush to the defence of the Hagia Sophia against its reversion to a mosque, lest they be portrayed as Islamophobic or violating the ideal of separation of church and state.

Though ideologically more aligned with laïcité secularism than the Republicans, the Democrats in the United States are most concerned to demonstrate that they are not anti-Muslim, so keeping silent on the matter will be their path forward. One or two Democratic Party members of congress who rely on Greek-American or Armenian-American votes may issue statements, but no legislative action to “punish” Turkey will result.

If Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gets his stated wish to have the Hagia Sophia revert to a mosque, he can expect little to no blowback from U.S. officials. The loss of entrance fees would be substantial, however Erdoğan has shown little concern of late for budgetary factors in his decision-making.

It is not a foregone conclusion that the Council of State will decide that Hagia Sophia should revert to being a mosque. It could rule that it should remain a museum but allow for its occasional for prayers to mark special dates, as was done on May 29, the anniversary of the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul. This would give Erdoğan a political victory within a legal loss.

It would leave him in control of when to use the Hagia Sophia for prayers commemorating historical or religious events to which he wishes to tie his presidency, allowing him to tell his support base that its mosque status has been restored, while maintaining most of the income from tourists – in particular the Orthodox countrymen of his good friend Putin.

Whether the Council of State exercises Solomonic wisdom or renders an unwise decision, one aspect of his imbroglio over the status of Hagia Sophia remains clear – President Erdoğan continues to set the agenda for Turkish courts and society.