By Jon Schwarz

The most peculiar thing about America’s 2018 apocalyptic imagination is the dog that isn’t barking. We have “Westworld” and “Terminator” and “Ex Machina” and a dozen more movies about artificial intelligence that decides to kill us. We have “The Day After Tomorrow” and “An Inconvenient Truth” and “Mother!” and maybe “Interstellar” and “Game of Thrones” about global warming. But we are notably bereft of movies, television shows, and novels about nuclear war.

You might believe this is because the danger of a nuclear Armageddon vanished with the Cold War. Or that we aren’t given to imagining it because it’s unimaginable. But neither of those things is true. In fact, we’ve stopped imagining the most terrifying possible future for ourselves at exactly the moment we most urgently need to do so, if we’re going to have any chance of avoiding it.

The good news – or at least the not incredibly horrible news – is that Donald Trump may be doing us the unexpected favor of kickstarting our nuclear imagination and sending us down a path where we can save ourselves.

There is widespread agreement among experts that the chances of a nuclear war are now higher than they were during the Cold War, not lower. This past January, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists set their doomsday clock at two minutes to midnight, as close as it’s been since it was created in 1947. As Eric Schlosser, the author of “Command and Control,” a history of America’s nuclear systems, puts it: “The people who are most anti-nuclear, the people who are most afraid about this, are the ones who know most about it.”

Trump and his intermittent threats of “fire and fury” are part of the risk, but by no means most of it. The doomsday clock was set at three minutes to midnight during all of Barack Obama’s second term. Back in 2007, George Shultz, William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and Sam Nunn – none of whom could be described as utopian peaceniks – declared that nuclear weapons present such “tremendous dangers” that they called for total nuclear disarmament by every country on earth.

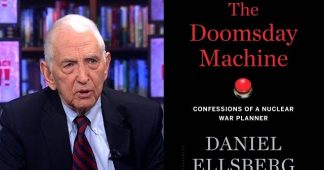

Looking forward, Daniel Ellsberg — who took part in U.S. planning for nuclear war before he leaked the Pentagon Papers, and recently wrote “The Doomsday Machine” — believes it’s “unlikely” we’ll survive another 100 years if we don’t completely eliminate nuclear weapons. The main reason we’re even here now, he says, is simple good fortune, rather than planning or wisdom, and our good fortune will almost inevitably expire.

So you might think this fact — at any moment we may, accidentally or on purpose, end human history – would be in the forefront of everyone’s mind. Yet it seems to occupy the U.S. consciousness to about the same degree as, say, the Kannapolis Intimidators (the 99.7 percent of readers unfamiliar with the Intimidators can learn more about them here.)

“Most of the time,” say James Blight and janet Lang, two of the foremost academic experts on the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, “most people give the issue no thought, no resources, and know next to nothing about the level of the threat [that] might careen the world once again into some shocking, unexpected crisis that spins out of control toward Armageddon. Are we that dumb? That ignorant? That much in denial?”

But there have been moments when the prospect of nuclear catastrophe was so tangible that it motivated millions of people to act to prevent it. Not coincidentally, these were also times when it was imagined in popular culture, over and over again. It took me five minutes to come up with this list of what I watched, read, and listened to growing up in the 1980s that was about nuclear war and its aftermath. I’m sure that if I took an hour it would be three times as long:

“War Games”

“Dr. Strangelove”

“Fail Safe”

“Godzilla”

“Planet of the Apes”

“Logan’s Run”

“Testament”

“The Atomic Café”

“When the Wind Blows”

“Threads”

“The Dead Zone”

“Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome”

“Time Enough at Last,” “A Little Peace and Quiet” and “The Vault”

“On the Beach”

“A Canticle for Leibowitz”

“Hell-Fire”

“The Fate of the Earth”

“We’ll All Go Together When We Go”

“Who’s Next”

“Russians”

“99 Luft Balloons”

Of course, it’s not the case that movies and books saved the world from nuclear apocalypse. As Ellsberg says, mostly we just lucked out. But we made some of our own luck by dreaming about the possible future right in front of us. Anti-nuclear activism and popular culture formed a virtuous circle, with culture keeping movements energized and energized movements enlarging the audience for the culture. It’s hard to imagine the success – even if partial – of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the 1960s and the nuclear freeze movement in the 1980s if all people had to motivate them was a bunch of pamphlets about nuclear throw-weights.

The most powerful example of this is “The Day After,” the 1983 made-for-TV movie about the effect of a nuclear war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union on Lawrence, Kansas. I doubt any child who saw it has ever forgotten it. Afterward, I developed a hobby of tracing concentric circles with a compass on maps of Washington, D.C., to figure out how far my family lived from ground zero and hence, how we were going to die. It was a relief to see that we’d be immediately cooked alive, rather than surviving to slowly die of radiation poisoning. (Now the internet lets you check this out for yourself for your city under any number of scenarios.)

“The Day After” became one of the most highly rated shows in U.S. history and gave a huge boost to the nuclear freeze movement. Edward Markey — then a Democratic representative from Massachusetts, now a senator – was the sponsor of a freeze resolution in the House, and called the movie ”the most powerful television program in history.” An anti-nuclear organization called it “a $7 million advertising job for our issue.”

Remarkably, “The Day After” also to some degree changed the mind of President Ronald Reagan. Reagan’s rhetoric and actions early in his first term had led the Soviet Union to believe that the U.S. was planning a sneak first-strike nuclear attack. Years after a 1983 series of NATO war games in Western Europe called “Able Archer,” it was revealed that the Soviets believed it was cover for a real attack and made preparations to pre-empt it — taking the world closer to nuclear war than at any point since October 1962. (Remarkably, “The Day After” was broadcast just weeks after “Able Archer” concluded.)

After leaving office, Reagan wrote in his autobiography that “The Day After” was one of several events that “made me aware of the need for the world to step back from the nuclear precipice.” In 1986, he discussed the total elimination of nuclear weapons with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and later, sent a note to the director of “The Day After,” telling him, “Don’t think your movie didn’t have any part of this, because it did.”

This is why it feels oddly ominous that I can’t think of anything I’ve seen about nuclear war from this decade. Wikipedia lists 24 movies on the subject during the 1980s. There have been just four so far in the 2010s, including such worldwide hits as “Die Gstettensaga: The Rise of Echsenfriedl.”

But now Trump may be accidentally helping us see reality again. Jeffrey Lewis, an arms control expert at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, says that Trump “is a one-man campaign for nuclear disarmament. He has singlehandedly reopened debates about presidential launch authority, disarmament, and how the United States relates to other nuclear-armed powers.”

Published at https://theintercept.com/2018/07/01/nuclear-war-movies/