By Bryan MacDonald

28 Sep, 2019

The Washington Post’s attempt to highlight “five myths about Ukraine” is more yarn than verity, and sets out to mislead readers. It also suggests fact-checking is now non-existent at the newspaper.

Since the ‘disinformation’ scare racket kicked off roughly five years ago, one thing has become very apparent: those who scream most loudly about it are often its biggest curators.

So the fact that the Washington Post has published a “myth-busting” piece on Ukraine which is largely untrue isn’t much of a surprise. But it’s notable in what it says about the once-venerable paper’s present agenda. Particularly as the standard of its Russia and Ukraine coverage plumbs the depths.

First off we’re told that Ukraine is not called “the Ukraine.” And this is absolutely fair. Purely because “the” suggests Ukraine isn’t an independent entity and is instead an appendage of something else. Like for instance, Crimea, which is commonly referred to as “the Crimea.”

So, the author Nina Jankowicz is correct to state “the country’s official name is Ukraine” and assert how “leaders, journalists and pundits should use it.”

Sadly, it all goes downhill from here.

The fabrications kick off when we are informed that the notion that “Crimeans want to be part of Russia” is a “myth.” Jankowicz claims that in 2014 Russian troops “rolled into Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and began wresting control of military installations and administrative resources from local authorities.”

For a start, this isn’t true. In reality, almost all Ukrainian military stationed in Crimea didn’t resist. So, there was no need to “wrest control.” In fact, as Reuters reported, a large percentage of Ukrainian soldiers on the peninsula defected as soon as the opportunity presented itself. This included around 50 per cent of local troops, including commanding officers, according to the then-deputy chief of the Ukrainian armed forces’ general staff, Alexander Rozmaznin.

The Washington Post goes on to claim that “the Kremlin has restricted access to the peninsula since its annexation, making it difficult to assess people’s true sentiments.” This is another obvious misrepresentation. Crimea is not a closed region. Anyone in possession of a Russian visa (or entitled to visa-free access to the country) can visit it as easily as Saint Petersburg, Sochi or Moscow.

In fact, it’s Kiev which has created impediments by making it an offense for any foreign journalists to visit Crimea from another part of Russia, instead insisting they should enter exclusively via Ukraine. In practice, this is tricky to do and requires a lot of time and effort. There are no direct flights or trains and permission must first be sought at the state migration service in Kiev. Which takes three days.

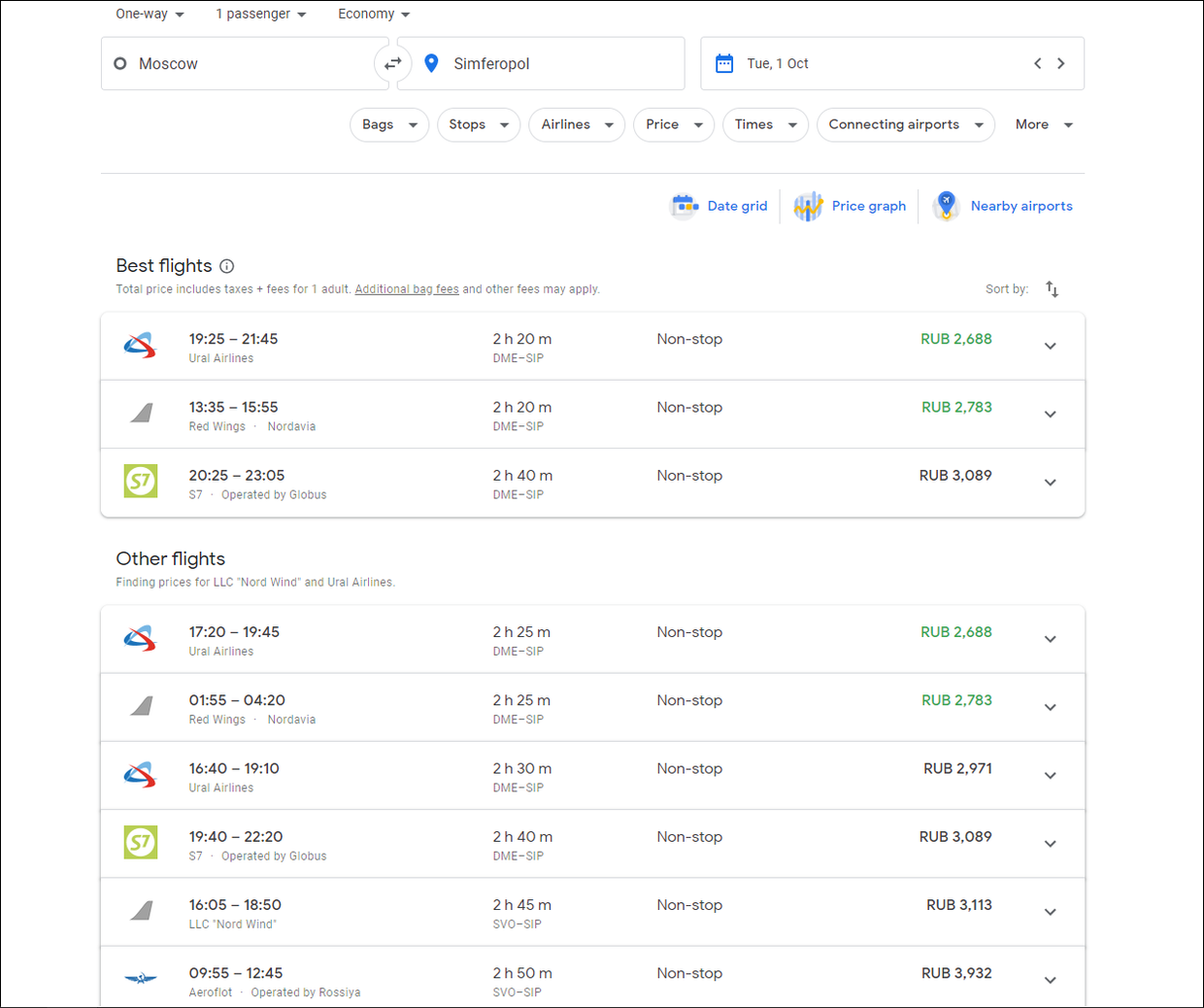

Then, assuming it’s granted, you’re looking at a nine-hour drive, on a largely poor road, to the frontier. Where delays can be expected. Afterwards, it’s another two hours to regional capital Simferopol. (A usual Moscow-Simferopol flight takes 2.5 hours). Naturally, this cumbersome process makes it hard for media to get a sense of what is really happening in Crimea.

As for it being “difficult to assess people’s true sentiments,” there have been numerous opinion polls carried out over the past five years. But Jankowicz chooses not to cite any of them, presumably because they would derail her narrative.

For instance, in the spring of 2014, only two months after 23 years of Kiev’s rule had effectively ended, the US state broadcaster BBG (since renamed USAGM and the parent of RFE/RL and Voice of America), in conjunction with American pollster Gallup, found that 82.8% of those surveyed believed the Crimea referendum (labeled “a sham” by Jankowicz) “reflected the views of most Crimeans.” Furthermore, 73.9% felt rejoining Russia would have a “positive impact on their lives.”

A month later, Pew Research, another famed American pollster, reported that only seven per cent of Crimeans thought the “Ukrainian government respects personal freedoms.” Also, a whopping 91 per cent insisted the vote to return to Russia was “free and fair” and 88 per cent wanted Kiev to recognise the results.

In Western media, publishing fake news about Russia is a good career move… with no consequences

(Op-Ed by Bryan MacDonald)@27khv https://t.co/O5kjPQ2A6w pic.twitter.com/NqpO89a8Xi

— RT (@RT_com) January 9, 2019

In 2015, leading German firm GFK discovered attitudes hadn’t changed. As reported by Forbes, “when asked “do you endorse Russia’s annexation of Crimea?”, a total of 82 per cent of respondents answered “yes, definitely,” and another 11 per cent answered “yes, for the most part.” Only two per cent said “mostly no”, and another two per cent said no. Three per cent did not specify their position. Notably, GFK found only one per cent of Crimeans felt the Ukrainian media “provides entirely truthful information.”

And just two years ago, ZOiS, a research institute bankrolled by the German Foreign Ministry carried out another poll. It showed that “86 percent of non-Tatar respondents” reckoned another referendum would produce the same result. As did the majority of Tatars themselves, who make up about 12 per cent of the local population.

These were all western surveys. Which cannot be dismissed as “Russian propaganda.” Yet, the Washington Post allows the writer to completely ignore them.

Even more damningly, in the very same week, Oleg Sentsov told a US state funded television network operating in Ukraine that “after 20 years [of rule by Kiev], Russia was more comfortable than Ukraine [for Crimeans]. You can try to deny it, but it’s a fact.”

This is the same Oleg Sentsov awarded the 2018 “Sakharov Prize” by the European Union for “freedom of thought,” who served a prison sentence in Russia for Crimea-related terrorism charges, which he insists were without foundation.

Next up, we are told that Ukraine is not “fighting a civil war.” This is because Russia supports separatists in the East, and there are allegations that Russian soldiers have fought alongside them. At the same time, the United States has been supplying lethal weapons to Kiev and Ukrainian soldiers are receiving training from NATO.

Nevertheless, even if Russia (or the US) decided tomorrow to openly dispatch a few thousand troops to the front line, or provide air support, it would actually remain a “Civil War.” There are considerable amounts of foreign involvement in the Syria and Yemen conflicts, which are still known as “Civil Wars.” Meanwhile, during the Spanish Civil War of the 20th century, the German Luftwaffe and Italian Aviazione Legionaria bombed civilians from the skies, but the name of the conflict is not the Spanish war of German aggression, or somesuch. Incidentally, the Soviet Union (of which Ukraine was then a member), also committed thousands of personnel.

Meanwhile, don’t forget that the Russian Civil War of 1918-22, featured foreign interventions by Britain, Japan, the US, France, Italy, China and more than ten other states, yet is still classed as an internal affair.

As the Canadian-Ukrainian academic Ivan Katchanovski has noted “The denial of the civil war in Ukraine is fake news, aka classic disinformation and propaganda.” His research has shown that over 94 per cent of people exchanged in prisoner swaps with separatists – or Russia – by Ukraine, during the five years of fighting were Ukrainian citizens. Which suggests the Ukrainian conflict is actually more of a domestic struggle than most of the 20th century European hostilities labeled “Civil Wars.”

The Washington Post’s fourth “myth” attempts to debunk the idea that Ukraine “is hopelessly corrupt.” Well, this is difficult to measure. The best known index, from Transparency International, judges Ukraine very harshly, but as it’s based on “perceptions of corruption,” it’s hard to actually quantify, making it an unfair metric. At the same time, well known Ukrainian politician and journalist Sergey Leshchenko, who is something of a Western media darling, told the BBC earlier this year that corruption “is Ukraine’s number one problem, it has to be stopped.” As it happens, Leshchenko was mired in his own financial scandal in 2016.

Jankowicz points to government “progress” in battling graft, citing the implementation of an “online procurement system for government tenders.” But it’s worth pointing out that Russia has had the same facility for 13 years now, and its effect has been mixed.

Respected journalist Ben Aris, of BNE Intellinews, opined in 2016 that attempts to battle financial malfeasance in this part of the world are doomed to failure because “corruption is the system in Russia and Ukraine,” and he may have a point.

Interestingly, earlier this year, NATO’s Atlantic Council adjunct admitted how between 2014-19, the Petro Poroshenko administration in Kiev had:

- “not dismantled Ukraine’s corrupt system of government or taken on the oligarchy”

- “not upheld the rule of law by removing corrupt judges, police or prosecutors, and replacing them with bullet-proof law enforcement institutions”

- “not protected reform-minded ministers or officials from harassment or obstacles by oligarchs, corrupt government officials, larcenous politicians, and organized crime;”

- “failed to create and protect a free and unfettered press by forcing oligarchs, criminals, and powerful vested interests to divest their media assets.”

- “failed to instigate or support the removal of immunity for members of parliament, who “sell” their seats and votes which is the basis of political corruption in the country.”

A pretty damning assessment, which flies in the face of Jankowicz’s claim that “the progress since the rejection of the corrupt Yanukovych regime in 2014 is unmistakable.”

The last of the five points made by the Washington Post concerns whether “Joe Biden lobbied to fire a prosecutor on behalf of his son.”

As this is a developing story, I’m not going to challenge the assertions here, and it’s possible, even if I did, that something could emerge in the coming weeks, which would make both of us wrong. All I will say (and it’s a personal opinion) is Biden clearly has a genuine fondness for Ukraine and he did try to force the deeply corrupt Poroshenko to clean up the prosecutor’s office, for good reasons.

However, surely everyone can agree it was also very wrong that his son, Hunter, was employed by a major Kiev gas company, just after Maidan. And this move presented very bad optics, while also not saying much for his judgment on foreign policy.

Not to mention how publicly bragging about getting the prosecutor, Viktor Shokin, fired might not have been too smart either, given it played into Donald Trump’s hands.

Lastly, let me make one thing clear. This is not an attack on Nina Jankowicz, who seems like a decent person (disclaimer: I follow her on Twitter), even if she is clearly ill-informed about Ukraine. The fault here is with the Washington Post, which failed to apply even basic standards of fact-checking before publication. And my purpose is to correct those errors.

Jankowicz has a book coming out next year, titled “How to Lose the Information War.” Well, by my reckoning, you lose an information war by peddling falsehoods. Because, ultimately, the truth will out. And that’s why, when covering Ukraine, or Russia, or any other topic, it’s best to maintain accuracy and veracity. Of course, regrettably, the line between journalism and activism is often very blurred on this beat.

Published at https://www.rt.com/op-ed/469854-ukraine-disinformation-war-wapo/