It may be hard to convey to the citizens of a republic with a female chancellor the peculiar depths to which the campaign for the presidential nomination of the Republican Party have now sunk. But perhaps, on reflection, not so hard. Psychosexual references surface in insecure times, and with them the yearning for a big man. Calm, reassurance, consistency and honesty are not the values that matter; bluster, threat, opportunism and craftiness rise instead. And support swells for Donald Trump.

Insecurity in America today comes in two flavors: physical and economic. The flames of physical fear are, however, quite weak. The trauma of 9/11 has faded; the incidents at Boston and San Bernardino remain unfathomable with the alleged perpetrators mostly dead. Meanwhile Paris is remote, it is not the iconic city for Americans that it was, say, in 1950, when its liberation was a fresh memory. Apart from black citizens facing white police, most Americans today feel fairly safe. Still, Trump evokes Paris, San Bernardino and Boston when he can.

Economic insecurity is pervasive. And to the slipping victim of globalization, the now-aging Reagan generation unmoored in part by the policies of the president they were raised to revere, Trump is the last throw. His economic platform, so far as he has one, has three planks: tough negotiations with China and Mexico to close the trade gap – a ludicrous fantasy of course, but never mind; a massive tax cut to gun the economy; and crucially, like Reagan, Trump would largely leave Social Security and Medicare alone, at least for now. His message is crafted precisely to Reagan’s voters, now themselves living on Treasury checks. For the rest – the wall, the deportations, waterboarding – it’s racist bluster, to be sure. But Trump is a New York real estate man; truly capable of anything. Brace yourself; as soon as he’s nominated he’ll be in the black churches and at least one mosque.

Split over economics

By far more interesting are developments on the Democratic side. Here the party has two echelons. Both are socially liberal and racially inclusive; religious reactionaries and white supremacists defected to the Republicans long ago. It is on economics that the Democrats are split. One side is mildly meliorist, tied closely to the finance-driven model of growth, open to the business lobbies, favorable to trade deals, prone to compromise on Social Security, and to elevate con jobs like microfinance to the status of major public policy achievements.

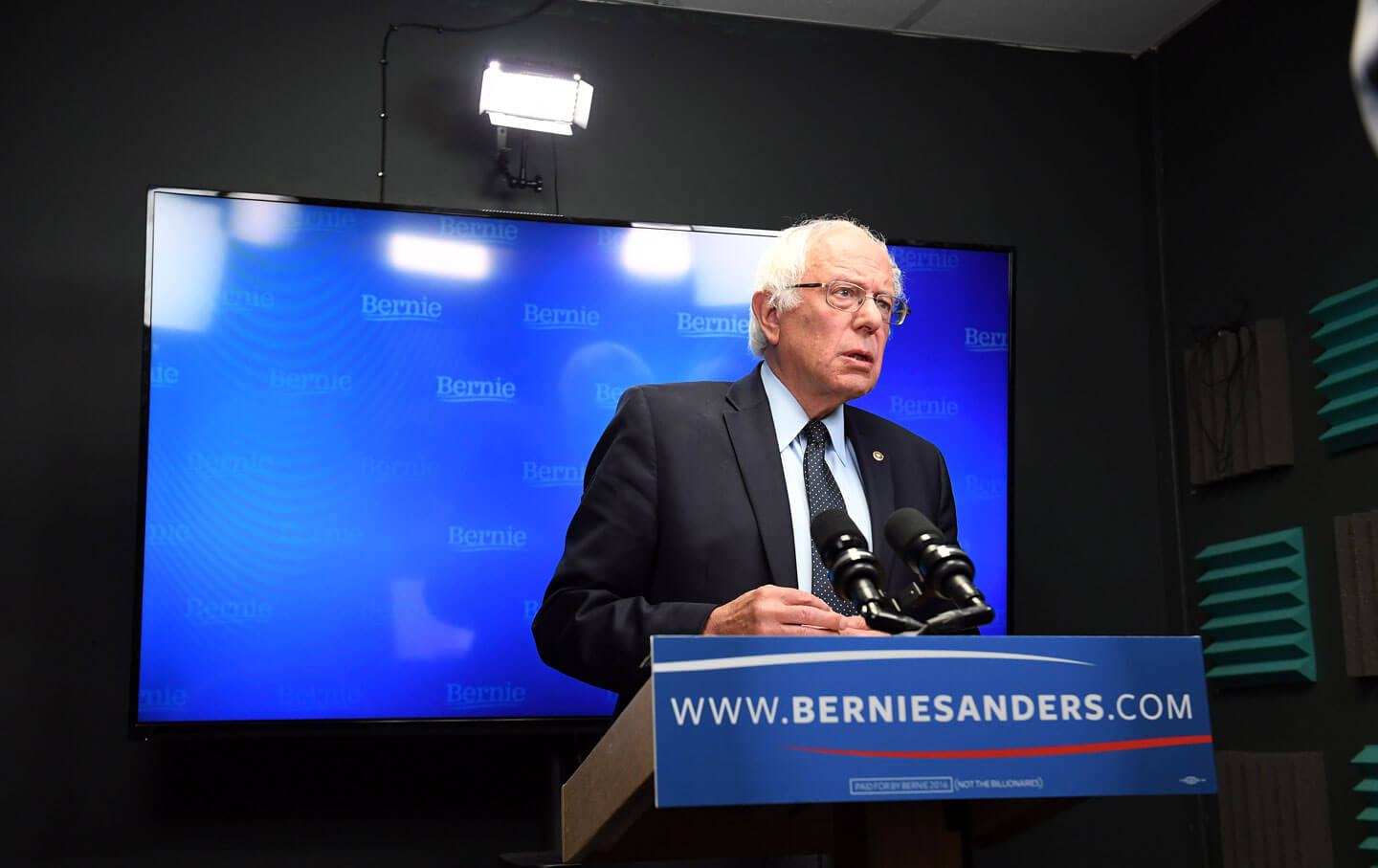

On the other side is the “Democratic base” – a loose grouping of young and working people who have been, for the most part, shut out of the high reaches of a party that relies on them for votes, and who are acutely conscious of, and embittered by, the privileges of big finance. This faction has had in recent years no voice. But this year it has one, in the seemingly-improbable figure of Senator Bernie Sanders.

And Sanders is riding the crest, precisely, of his economic program, which has three major planks: a $15 minimum wage, tuition- and debt-free public higher education, and single-payer universal health insurance. These would be funded by taxes on the wealthy; Sanders is only an incidental Keynesian. His program would not have raised an eyebrow in 1960s Germany, but to young Americans, in today’s finance-infested United States, it has the true flavor of political revolution.

In Sanders they trust

So Bernie Sanders has caught fire among the young – among students, among parents with children who will one day reach university age, among low-wage working people and among those who still lack health insurance or find the burden of paying the premiums of Obamacare hard to handle. To this generation, the promise of Sanders’ program borders on a transformation.

As a result, there has opened up in the politics of the Democratic Party a generation gap not seen since the Beatles arrived here in 1964. Among voters under 45, Sanders’ margins typically approach or exceed 60-40, which pays off heavily in caucus states and university towns. Among older voters, and in the African-American community especially in the South, familiarity prevails and Clinton enjoys similar margins. Given the weight of Democratic officeholders at the convention, her nomination remains more likely than not.

But the future plainly lies with Sanders. Demography is destiny. It is he, not she, who has captured the young and redefined American politics for the next generation. He has set the agenda for the future. It is his mantle – not hers – that even now we observe ambitious and promising younger American progressives positioning themselves to claim. Even if she becomes president, in four years the party will belong to his people, and the country will belong to them, soon after that.

In the end, it is not Donald Trump who has captured the revolutionary spirit of Ronald Reagan this year and for the years to come. Whatever happens, there will be no Trump Revolution. No – the pace of the next revolution has been set by a figure at least as avuncular, as reassuring, and as clear in his call and message as Reagan was. A figure who happens to be a 74-year-old, non-observant Jewish socialist from Vermont.

James K. Galbraith holds the Lloyd M. Bentsen Jr. Chair in Government/Business Relations and a professorship of Government at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin. His new books are Inequality: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford, March), and Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice: The Destruction of Greece and the Future of Europe (Yale, June).