By Theo Panayides

February 5th, 2018

The owner of a newspaper attacked in the north last week for defying Turkey says he is the freest person in Cyprus. THEO PANAYIDES meets a man proud to call himself a marginal

A day before the first round of the Greek Cypriot presidential elections, I cross the checkpoint to the occupied north and walk about 200m, down Ikinci Selim Street. I’ve already been warned that there’s no sign on the building – just a buzzer at the front door, and a small handwritten sticker reading ‘Afrika’.

I have to buzz several times before someone answers, then it takes a while to explain why I’m here – namely, to interview Sener Levent, the editor of Afrika newspaper. The dingy office, up the steep steps of an old narrow staircase, has seen better days. I sit on a squeaky sofa, facing an array of cheap plastic chairs arranged in a circle, as if for a PTA meeting. On the walls are photos of street demonstrations and a poster commemorating Mishaoulis and Kavazoglou, the Greek and Turkish Cypriots whose bicommunal friendship led to them being murdered by extremists in 1965. Fluorescent lights cast a hard, ugly glare.

It takes a few minutes to discern why the atmosphere in Afrika’s waiting room is so gloomy. It’s because the windows have been boarded up – and in fact, as becomes apparent when I peek through a small diamond-shaped hole in the plywood, there aren’t any windows behind the makeshift board, just a small balcony. The reason for this is the same reason why there isn’t a sign on the building: a few days before our meeting, supporters of Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan – responding to a speech where he urged “my brothers in north Cyprus” to punish Afrika for an article criticising Turkey’s ‘occupation’ of Afrin in Syria – attacked the newspaper’s offices, smashing windows and climbing up to this very balcony. Had police not stopped them at the last minute, they’d have stormed inside, intending violence to the newspaper staff and Sener personally.

It’s something to bear in mind – indeed, it’s impossible to ignore – while talking to the small, doleful man in the private office adorned with pictures of Che Guevara and Turkish film director Yilmaz Guney: while newspapers in the Republic of Cyprus are wasting time on the candidates’ latest empty promises and pointless bits of mud-slinging, this Turkish Cypriot paper is literally fighting for its life, facing up to an authoritarian leader who has no qualms about treating the press as an enemy. Sener sits behind his desk, flanked by his daughter Elvan who’ll be doing the translating. His English isn’t fluent enough (though I get the sense he understands more than he lets on), his second language being presumably Russian; he studied Journalism in Moscow, back in the 60s. Elvan looks tired, like she hasn’t slept very well; I apologise for having come on a bad day. “These days are all like this,” she replies, obviously feeling the pressure.

It’s not just the fact of being personally targeted by Erdogan; the day before our meeting, 5,000 people marched for peace and democracy in the streets of Nicosia, placing Afrika in the crosshairs of what seems to be increasing tension between the two faces of Turkish Cyprus. It’s enough to make anyone nervous – but Sener himself chuckles quietly when I ask if he was frightened during the attack: “Yok,” he replies in Turkish, shaking his head. But surely his life was in danger? “I know, but I wasn’t afraid. If I were afraid, I’d have been afraid long ago, because we’ve had many attacks since we’ve been publishing. We were shot at twice. They came to kill me here at the newspaper, directly, in 2011.”

To be honest, I wish I spoke Turkish; Elvan does a more than valiant job of translating – but her dad is obviously a character, and seems like he must have a very distinctive way of expressing himself. His head is egg-shaped, the voice growly, the face pouchy, the grey hair fashionably long in the style of some bohemian academic from the 1970s. He’s been in the newspaper business since his teens (he’ll be 70 in March), initially at a paper published by his older brother, then at various Turkish and Turkish Cypriot outlets as journalist and editor – then, since 1997, at his own paper, initially called Avrupa (‘Europe’), its name waggishly changed to Afrika in 2001 as a dig against the corruption of political life in the north.

Sener provokes strong reactions, on both sides of the Green Line. When I mentioned I was going to be interviewing him, one friend said he was a hero, a ‘leventis’ (a play on his surname, meaning something like ‘splendid fellow’ in Greek), another called him a clown, while a third dismissed him as a provocateur. He himself is undoubtedly aware of his notoriety, and seems to thrive on it; he seems quite surprised that I don’t know about the attempts on his life in 2011. “How long have you been a journalist?” he asks through Elvan, as if wondering if my ignorance could perhaps be excused by being a newcomer to the profession. I don’t do hard news, I explain, only profiles and features, and he nods with a smile. “Doesn’t matter,” he assures me in English, magnanimously.

The two attempts to kill him came within four months of each other, both times deflected by a brave employee named Ali Osman. The first time, a man came to the door with a ‘special’ envelope which he claimed had to be delivered to Sener personally – then, after Osman fobbed him off, the man fired his gun from outside, through the closed door, sticking a piece of paper on the door which read ‘Next time, it will not be like this’. The second time was more bizarre because the hitman (not the same man) came to visit Sener in his office, claiming he’d been hired to kill him but, having asked around and been told that Sener was “a good man”, had decided against it; they shook hands, and even took a photo together – only for the man to return 10 days later, shooting Osman (fortunately, the bullet only grazed him) and forcing Sener to barricade himself in his office. This weirdly erratic assassin was later arrested, tried, and sentenced to 10 years in jail – but, says Sener, never revealed who had hired him.

I’m struck by the lightly amused way in which he tells the story (granted, he’s told it before); he even takes advantage of Elvan’s translation to sneak a peek at the latest issue of Afrika – its front page leading with a photo of the previous day’s demo with the headline ‘Görev tamam’ (‘Mission completed’), ironically echoing what Erdogan’s thugs had declared a few days earlier. So tell me, I ask – trying to get a reaction, more than anything – do you think this job is worth dying for?

He chuckles again: “Everyone dies in this world”.

But maybe he enjoys it on some level? Making trouble?

“Freedom doesn’t mean doing what you want,” he replies gnomically. “It means not doing what you don’t want to do. So I consider myself – and I think I probably am – the most free person in Cyprus! I don’t do things I don’t want to, and I do what I love; I am doing the profession that I love. I think what kills people, in reality, is fear. People can only be happy when they come out from the sea of fear.” Afrika, he claims, has been fearless, broaching subjects no-one else dared mention – like for instance the infamous ‘bath murders’ of a mother and her children in 1963. “These photos were the iconic propaganda photos of the Turkish regime in the north,” he explains – but Sener has publicly questioned whether the official version (that the family were killed by Greek Cypriots) is true, or whether they may have been killed by the Turkish side to encourage Turkey’s intervention. “Here, it’s not even possible to ask this kind of question,” he sighs. “There are many people who prefer to live in a lie, in this world. But I prefer to live in reality, no matter how bitter it is.”

Are his views shared by the majority, though?

“I never thought that my views are the views of the majority,” he replies with dignity.

How does that make him feel?

“It makes me feel that I’m on the right path – because history was written by the minorities. How many people thought like Archimedes? Or Galileo? Or Newton, or Socrates? These people were all lonely people, and nobody told them ‘You are right, you are telling the truth’… [Rauf] Denktash said about us, in Afrika, ‘These people are not more [in number] than the fingers of one hand’. Others found a more popular word for us, they call us ‘marginals’.” Sener chuckles, obviously proud of the designation. “History is written by the brave minority,” he concludes. “The majority is a scared, fearful crowd, and I never wanted to be like them.”

Fighting words indeed, especially under the circumstances – though note that passing reference to ‘lonely people’; there’s a downside to being such a gadfly. He may be fearless, I ask – but is he also, perhaps, rather melancholy? “I’m not a very happy person. It’s my nature,” he agrees. “I grew up in a poor family. It was the kind of family where no-one even knows, or cares, when is your birthday.”

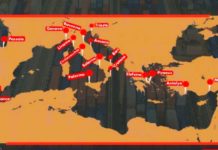

His parents were illiterate, hailing from the village of Terra; his dad sold live chickens at market. (The family may have been poor, but it seems to be close-knit; all three remaining brothers – Sener is the youngest of five boys – now work at Afrika.) At 15, he was handed a gun and stuck behind a barricade on Ermou Street, fighting in the troubles of 1963 like so many other Turkish Cypriot children. “People don’t know, in the south, that the situation on our side was like this,” he says wearily, noting my surprise. “Because, in the south, people also prefer to live with a lie”. He talks briefly of Tochni, Maratha, Santalaris, villages – he says – where Turkish Cypriots were murdered en masse, though Greek Cypriots deny it. Neither side should be let off the hook, in Sener’s telling. Truth transcends checkpoints.

What about away from the office? Is he also a bit of a ‘marginal’? (Work, it should be noted, is central to his life; he takes one day off – New Year’s Day – and hasn’t had a holiday in 20 years.) Of course you are, Elvan interjects, you don’t even go to the beach in the summer! (Her father denies this.) He’s not a loner, and enjoys spending time with friends – yet he does seem to be a bit of a misfit. “I’m not happy at all in the society I’m living in… I don’t enjoy speaking with someone who’s never seen even one film by Almodovar, or read any books by Dostoyevsky”. Sener is a major film buff with a penchant for arthouse (Ingmar Bergman is another of his favourites), and a bit of an intellectual; Fourier gets quoted in our conversation, and he also cites Hamlet – the “readiness is all” speech – to explain why fear of death is absurd, especially when you’re almost 70. Mustafa Akinci is three months older, he adds mischievously, yet he still lives in fear: “What is stopping him from being more brave, at this age?… Call the foreign media, BBC, CNN, Euronews,” says Sener, addressing the Turkish Cypriot leader, “and announce to them that we’re opening Varosha tomorrow, and see what happens! Will Turkey kill you? Why is he afraid?”. The provocateur laughs merrily, delighted by his own provocation.

Say what you like about Sener Levent (and people do), but you have to admit he doesn’t falter. He’s just been attacked by a baying mob, engineered by Erdogan himself – he even agrees it’s “a very serious situation this time” – yet he won’t back down, won’t admit to being scared, won’t consider shutting down the paper. Is it narcissism? A martyr complex? Just sheer guts? Maybe force of habit, after a lifetime of being on the fringes? He mentions having been deeply affected, as a child, by the murder of Ayham Hikmet, a newspaper editor shot by paramilitaries. Does he somehow see that as the ultimate price one must be willing to pay, in order to be free in this society?

Maybe so; but Turkish Cypriot society has grown more constricted in his lifetime, and is now more beleaguered than ever. Sener sighs unhappily: “This place is not Cyprus anymore,” he admits, indicating the world beyond his boarded-up windows. “This is Turkey. The majority is from Turkey, the population. Everywhere – all the shops, kebab places, sweet shops – everywhere belongs to people from Turkey. All these five-star hotels also belong to them. So now, Turkey has total control over the north”.

Where does that leave him, and his brand of stubborn individualism? “I’m one of those who believe that Turkey will finally get out of Cyprus – but I don’t know when,” he replies, somewhat quixotically. “I don’t believe that Cyprus will always stay as a divided island.” After all, he adds, “all the occupiers in Cyprus, everyone left. No occupier stayed in Cyprus, throughout history. Maybe 100 years, maybe 200 – but, in the end, they all left.”

Sure, I agree – but is Turkey even an occupier? Many on his side don’t seem to think so.

Sener Levent smiles shrewdly, replying in Turkish, then waits for his daughter to translate. “This is the majority who think that. I am not that majority!” explains Elvan – and her father watches as I take in that punchline, adding his chuckle to my own. When things look desperate, in other words, the answer is to wear that desperation as a badge of honour. If your position gets lonely, rejoice in your loneliness. I walk out to daylight, away from the boarded-up windows, and cross the checkpoint the other way, back to the happy inertia of TV debates and politics as usual.

Published at https://cyprus-mail.com/2018/02/05/threat-newspaper-owner-living-reality/