Jair Bolsonaro and India’s New Circle of Friends

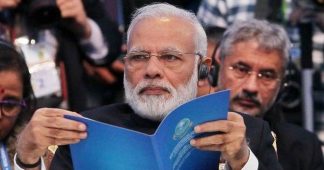

Under Narendra Modi, India has developed closer ties with countries led by populist leaders.

By Sidharth Bhatia

Nov. 19, 2019

On January 26, a day when India became a Republic, Jair Boslonaro will be seated along with Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the podium at Rajpath as the officially invited chief guest. A foreign leader has been traditionally invited on the day when India celebrates its diversity, showcases its military prowess and generally puts its best foot forward. Heads of state and heads of governments as well as distinguished statesmen from all over the world have attended the ceremony, ranging from Queen Elizabeth to President Tito to Nelson Mandela.

While over the years, there have been some questions about whether there should be so much militaristic display, it is a proud day for India, because the founding of the Republic in 1950 was a very significant step for the newly independent nation. The idea of the Republic is to emphasise the equality of citizens and lay emphasis on constitutional values that have guided us over the decades.

This year’s choice has been criticised widely because Bolsonaro is a deeply divisive leader with some astounding views – he is homophobic and has made misogynistic and bigoted statements. His pandering to identity politics and severe antipathy to leftists and all those espousing environmental and gender-related causes – he said he would get the country rid of this ‘crap’ – has won him popular support.

Though his success and elevation is unique to Brazilian politics and economic malaise, he is one link in the growing chain of populist and somewhat outrageous leaders that are emerging in many countries. They have no compunctions in expressing themselves in the crudest ways, as long as it appeals to the masses and wins them the approval of the masses. They also have limited patience for dissidents and are unabashedly right-wing.

His ideology by itself would not be a problem, but many of his actions make him – or should make him – an unsuitable candidate to be given such an honour by India.

But not surprisingly, the Modi government thinks otherwise. It may even consider him the perfect kind of friend to have, because his outlandishness may have a resonance in the current scheme of things. In fact, he fits in right into the pattern of the new group of friends that this country is cultivating.

India’s foreign policy principles

Indian foreign policy over the years has tried to be flexible with changing times, but some founding principles remain the same. Often the country has had to maintain good relations with otherwise unsavoury leaders elsewhere, but that has been for strategic reasons rather than because of any common values.

India was a big supporter of the Palestinian cause through thick and thin and shunned Israel for decades. When the cold war ended, P.V. Narasimha Rao gradually began a thaw with Israel, but did not stop support to Palestine. Under Modi, India has gone full steam ahead in building a close relationship with Israel, a country that he and others of his ideological ilk have long admired. (Somehow they have also managed to retain a deep admiration for Adolf Hitler, unmindful of the inherent contradictions. The Israelis too seem to overlook that.)

Modi became the first Indian prime minister to visit Israel and was at his customary hugging best with hardline leader Benjamin Netanyahu, who then came to India. Modi featured in the Israeli leader’s election campaign. The bonhomie has resulted in closer links in trade, weaponry and even Bollywood. Benjamin is another hardline, nationalist leader with a determination to expand further into West Bank and against the notion of a Palestinian state. The shift from a Palestinian-centric policy in the region is complete.

Similarly, Modi has developed unusual warmth with Mohammed bin Salman, a nationalist hardliner who, while easing some of Saudi Arabia’s stringent social restrictions, like allowing women to drive, has nonetheless come down heavily on dissenters both within and outside his country. India’s ties with Saudi Arabia have traditionally been good – with a large Indian population there and the Indian demand for petroleum they would have to be – but there is much more personal bonhomie since Modi came in.

A country’s government chooses its friends according to its own self-interest and strategic objectives, so per se, the Modi government’s vision has to be its own. But there is also little doubt that he feels more comfortable with hardliners rather than the more tolerant leaders, nationalist-minded politicians rather than liberals.

The world has seen a rise in populist leaders. Rodrigo Duterte in the Phillipines, Recep Erdogan in Turkey and, of course, Donald Trump in the US are other examples. India has limited interest in the Philippines and Turkey’s president has criticised India on Kashmir, so is beyond the pale.

As for Trump, he may have held hands with the Indian prime minister at the Howdy Modi rally in Texas, but he has to balance ties with Pakistan too. Besides, he is too focussed on pushing through pro-America trade deals. Nor does President Trump have the kind of power that say, Mohammed bin Salman would have – while the state department may have been tepid in its reaction on Kashmir, the Congressional hearings were far more scathing. It is there that Indian efforts have to be directed.

A clear pattern

The pattern is becoming clear. India’s new best friends are of a type quite different from the past, when, guided by the foundations laid down by Jawaharlal Nehru, this country supported liberation struggles and the underdog. The world has changed of course, but some issues remain unresolved, Palestine being a good example. Friendship with Israel needn’t have meant giving up support to the Palestinians.

There is another reason too. The Modi government needs all the support it can get from other countries, and some countries have become lukewarm toward India. The rising anti-minority violence, the ramping up of majoritarian sentiments and lately, events in Kashmir, where a constitutional arrangement was changed suddenly and a lockdown imposed have shocked the world. Reactions from governments have been muted, not in the least because of India’s investment possibilities. But even so, leaders like Angela Merkel have pointed out that the situation in Kashmir is troubling and ‘unsustainable’.

The manner in which the Modi government reached out to Members of the European Parliament from far-right, anti-Islamic parties shows that it is scrambling for endorsement from somebody, anybody. An invitation to a Liberal Democrat MEP from Britain was withdrawn because he wanted to roam around freely and see the situation in Kashmir for himself. That wouldn’t have done.

There is a certain level of comfort, therefore, in gathering like-minded people around you, whose values you related to and whose ‘toughness’ you admire. The club of such leaders, who have no time to ‘pander’ to the minorities, namby-pamby causes such as the environment or gay rights, or indeed democratic values such as tolerance towards dissidents, is growing. India is becoming a proud and honoured member of this club.

Published at https://thewire.in/politics/india-narendra-modi-jair-bolsonaro