By Jean Shaoul

27 December 2017

Prime Minister Theresa May’s Conservative government is establishing a $1 billion investment fund with China to back China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Her predecessor, David Cameron, will become vice-chairman of the fund, which is being set up by Cameron’s friend and Tory Peer, Lord Chadlington, on whose behalf Cameron lobbied Beijing. Douglas Flint, the former group chairman of HSBC bank, will become Britain’s envoy to the project.

The BRI, also known as One Belt One Road (OBOR), is a massive infrastructure investment project for high-speed rail, roads, Internet links and port facilities aimed at more closely integrating the Eurasian land mass.

As well as boosting economic growth, Beijing regards the project as a means of establishing closer ties with Europe and thus bypassing the US, which has opposed European participation as part of its broader effort to isolate China diplomatically, economically and militarily.

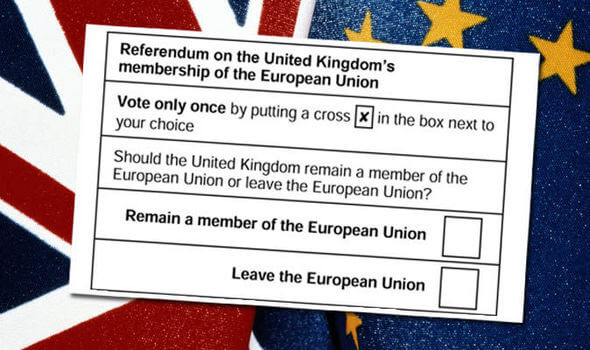

Chancellor Philip Hammond announced the fund along with a raft of new investment agreements finalised during his two-day visit to Beijing, as part of Britain’s efforts to boost its global trade and investment links before leaving the European Union in 2019. There will be export credit guarantees to support up to £25 billion in investments in BRI projects. There will also be a $50 million matching contribution with China to the $100 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) to expand operations into less developed countries. The AIIB was set up in 2015 as China’s equivalent to the World Bank. Britain was the first Western country to pledge its participation.

Other measures include a direct channel for trading China’s renminbi on London’s foreign exchange markets via R5, a London-based fintech (financial technology) firm that will provide the trading platform for Chinese banks, and a Shanghai-London Stock Connect that will allow companies in each market to list depositary receipts in the other.

The former prime minister and his chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne, made economic ties with China, centring on Chinese investment in the UK, a central axis of their economic policy. In March 2015, Cameron defied pressure from the United States and Britain’s own security agencies and joined the Chinese-sponsored AIIB, a decision that reflected the interests of the City of London in exploiting the opportunities that could open up.

Cameron’s new job testifies to the revolving door between high political office and a financial career. He follows Sir Danny Alexander, a Liberal Democrat chief secretary to the Treasury in Cameron’s Conservative/Liberal coalition, who became vice-president of the AIIB in Beijing after losing his parliamentary seat in 2015.

Cameron’s role was approved by the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments (ACOBA), which gave him special dispensation to circumvent the normal two-year ban on former British ministers taking jobs that capitalise on their insider knowledge of government.

The British economy has become ever more dependent on the speculative and parasitic activities of its major banks and finance houses, which view participation in the AIIB as an opportunity to profit from enhancing the global role of China’s renminbi as Beijing’s economic and financial power increases.

The announcement points to the divergence between Britain’s commercial interests and those of its foremost ally. For most of the post-World War II period, Britain has been able to “punch above its weight” because of its supposed “special relationship” with the United States. Now that relationship is coming under increased strain as President Donald Trump’s increasingly reckless policy in both the Middle East and East Asia cuts across Britain’s commercial interests.

While May was initially cautious about making overtures to China, ordering a review of the Hinkley nuclear power station in which China is involved before giving it the go-ahead, she has now given the nod to BRI and Britain’s involvement in it. A major factor in her calculations has been the importance of securing trade deals and attracting investment after leaving the EU, the world’s second-largest economy, in 2019.

This has become urgent, given that Trump’s promises of a favourable post-Brexit trade deal with the US are both vague and problematic, not only due to Trump’s “America First” policy, but also in the wake of high-profile rows over Trump’s re-tweeting of a fascist Britain Firster’s anti-Muslim videos and Britain’s refusal to join Washington in recognising Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

Washington’s intense opposition was made clear. An opinion piece in the Washington Examiner described Cameron’s appointment as “undercutting a US-led international order built on fair commercial law.”

This divergence of interests is echoed throughout Europe. When Cameron announced, with little if any consultation with the US, that Britain would become a founding member of the AIIB, other major European countries swiftly announced their intention of joining. Washington viewed the bank as a strategic rival to the US-dominated World Bank and the Japan-led Asia Development Bank and denounced the move by the European powers as part of “a trend towards constant accommodation” with China that was “not the best way to engage a rising power.”

Then-Chancellor Osborne could not afford to ignore the fact that China’s economy is expected to be twice that of the US economy by 2030, and that Chinese investment in Britain had grown by 85 percent annually since the Cameron-led coalition government took office. He went to Chengdu, China and urged firms there to bid for seven contracts worth £11.8 billion covering the first phase of a proposed high-speed rail service between London and Birmingham. He also invited bids for £24 billion in further Chinese investment in northern England under the government’s “Northern Powerhouse” project, designed to link deindustrialised northern cities so as to facilitate the exploitation of a 15-million-strong population by international corporations.

In October 2015, Cameron feted Chinese President Xi Jinping during his state visit to Britain, when trade and investment deals worth £40 billion were agreed.

China has become Britain’s seventh largest trading partner, making China the UK’s second-largest non-European trading partner. Bilateral trade rose to more than $80 billion last year, up 8.9 percent from 2015.

China’s investment in the UK has also risen, reaching $11.15 billion (£8.4 billion), double the amount in 2015, far more than in Germany, France and Italy combined. This includes the £19.6 billion project to build a nuclear power station at Hinkley Point, in which China’s state-owned CGN has a one-third stake; Chinese developer ABP’s Royal Albert Dock re-development in east London; and the “Cheesegrater”—the tallest buildings in London’s “Square Mile” financial district—which was sold to Hong Kong-based CC Land for £1.15 billion this year.

Last April, the first UK-to-China freight train left its terminal in Essex to begin a 7,500-mile, two-and-a-half-week journey to Zhejiang province.

As far as the US is concerned, the advance of China’s economic influence in Asia and Europe expressed by the rail link and the enhancement of its military and strategic capacities are inseparably linked, and together represent a growing threat. This places Britain in a quandary: How far can it go in pursuing its own interests without jeopardising the strategic relationship with the US, the world’s dominant military power?