By Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

Dec 18, 2024

The Turkish government has secretly launched a plan to establish a parallel shadow structure to govern Syria following the ouster of President Bashar al-Assad, facilitated by a Turkish intelligence-backed blitzkrieg offensive involving rebels and jihadist groups, Nordic Monitor has learned.

The plan, initially tested and partially implemented in areas controlled by the Turkish army in northeastern Syria since 2016, is set to expand nationwide if rebels succeed in maintaining control over the entirety of Syrian territory.

Under this plan, the Turkish government intends to appoint senior officials under the guise of advisors to assist Syrian authorities with managing various government portfolios. These officials will be instructed to remain behind the scenes to avoid the appearance of interference in the internal affairs of either the interim government or its successor following the anticipated elections.

Turkey would justify deploying a large contingent of advisors across various branches of the Syrian government as providing essential support to enhance the country’s governance capacity, sharing expertise and aiding in rebuilding its weakened institutions.

For the plan to succeed, Turkey’s top priority is to strengthen security in Syria, consolidate territorial gains and offer hope to millions weary of decades of repression, internal conflict and violence. The Turkish plan envisions integrating existing Syrian army troops into a new military force led by the Syrian National Army (SNA) and jihadist groups such as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

Ankara is determined not to repeat the mistake the Americans made in Iraq by disbanding the entire national army. The de-Baathification process in Iraq led to the rise of armed militias and years of internal conflict and violence. If such a conflict unfolds in Syria, it will have lasting repercussions for Turkey, which shares a 911-kilometer-long porous border with Syria.

The roadmap begins with the establishment of a security infrastructure through the integration of militia and rebel groups with the Syrian army and law enforcement agencies, following the removal of individuals with past criminal involvement. This is undoubtedly a challenging task. To prevent the emergence of new armed militias that could challenge the post-Assad rule, Ankara aims for the HTS leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa (Abu-Muhammad al-Julani), to engage with minority groups, including Kurds and Alawites. However, it remains uncertain how successful this effort will be.

On the civilian side, Ankara plans to leverage senior Syrian figures who were part of the Istanbul-based opposition, established with the support and guidance of the Erdogan government and its intelligence service (MIT), in 2011. Some of the names already circulating in Ankara halls include Ahmad Moaz al-Khatib, a former imam of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, who led the Syrian opposition bloc, the Syrian National Council (SNC), from Turkey between 2012 and 2013.

Another key figure is Riyad Farid Hijab, the former prime minister of Syria who defected to Turkey in 2012 and later assumed the role of head of the Syrian opposition to lead negotiations in the Geneva process in 2015 before resigning from that position. Khaled Khoja (Halid Hoca), a Syrian Turkmen who acquired Turkish nationality and changed his name to Alptekin Hocaoğlu, is another prominent individual involved in these efforts.

Khoja led the Istanbul-based opposition group, the SNC, between 2015 and 2016. However, his relationship with Erdogan may be strained, as Khoja later joined Turkey’s Future Party, led by Ahmet Davutoğlu, who has parted ways with Erdogan.

George Sabra, a Christian Syrian politician who led the SNC in 2012, is another name being considered by the Turkish government. Sabra left the SNC in 2018 and currently resides in Paris. His potential inclusion in the interim government could enhance its legitimacy and help counter criticism that Syria is at risk of being governed by jihadist figures.

Aref Dalila, a Syrian economist critical of the Assad regime despite coming from the same Alawite background, currently resides in the United Arab Emirates. While it is unclear whether Dalila is willing to participate, his name is reportedly under consideration in Ankara. Abdulbaset Sieda, a Kurdish-Syrian politician who briefly led the SNC, is also favored by the Erdogan government due to his opposition to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and its affiliates in Syria.

Turkey has already assembled an elite group of Syrians selected from the large pool of approximately 3 million Syrian refugees in the country, with plans to send them back to Syria. Many have been encouraged to return to provinces, cities and towns to help consolidate the gains of rebel forces. According to the Turkish Interior Ministry, 7,621 Syrians returned to Syria between December 9 and 13, with more expected in the coming days.

Another step Turkey is considering is reaching a swift agreement with the interim government to legalize the presence of its troops in Syrian territory. This would be followed by a comprehensive military training and defense cooperation agreement, enabling Turkey to help shape the newly formed Syrian army. In his annual review with reporters last week, Turkish Defense Minister Yaşar Güler signaled that such agreements are already in the works.

A further step in Turkey’s plan is to establish a constitutional commission tasked with drafting Syria’s fundamental charter and determining the status of minorities, particularly the Kurds. To facilitate this, Turkey aims to propose the creation of a reconciliation commission that would ease the transition process and unite alienated groups. This is seen as crucial for ensuring the legitimacy of any future Syrian government.

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s leader is seen with Turkish intelligence agency chief Ibrahim Kalin in Damascus on December 12, 2024

The fundamental challenge, however, remains how to finance Syria’s economy, which has been devastated by internal conflict, pervasive corruption and international sanctions. Turkey hopes to enlist its close ally, the wealthy Qatar, and potentially other countries to fund the process. The Turkish Foreign Ministry has already been tasked with organizing an international donor conference to support the effort.

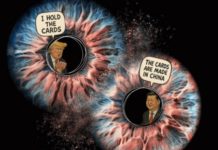

While Ankara will likely present these efforts with carefully crafted talking points framed within rhetoric of international and regional cooperation; in reality, President Erdogan aims to shape a new Syria in his own image, with religion, Turkish identity and neo-Ottoman revisionism as dominant characteristics.

The large areas occupied by the Turkish army and Turkey-backed rebel groups in northern and northeastern Syria for the past five years offer clues about Turkey’s vision for a future Syria. In cities such as Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ayn, where Turkish military control has been established, Turkish deputy governors from border provinces have been appointed as the effective rulers, despite official Syrian figures being presented as governors. The Turkish deputy governors have been the ones calling the shots behind the scenes.

Security in these areas is maintained through the joint efforts of the Turkish military, the SNA, Turkish intelligence and affiliated jihadist and rebel groups. Turkey acted swiftly to rebuild essential public services, including water, electricity, healthcare, education, construction, communication and infrastructure, in order to secure the loyalty of the local population. Hundreds of experts and advisors from the Turkish government were deployed to oversee these efforts across various sectors, along with the provision of logistical supplies and funding.

The administration in these areas is officially delegated to local city and town councils for the sake of legitimacy, although the real decisions are made by Turkish officials operating behind the scenes. This approach was part of the original plan devised by Turkey in 2011, when the Erdogan government decided to overthrow the Assad regime by force. Turkey not only coordinated the formation of a rebel army under the SNA, then known as the Free Syrian Army, but also set up parallel local councils to govern Syrian towns, cities and provinces.

Members of these councils were selected from Syrians loyal to the Turkish government or those who would not challenge Turkish rule, often in exchange for perks and benefits in the new Syria. However, Turkey’s plans were disrupted with the Russian intervention in Syria and US cooperation with Kurdish groups linked to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party in 2015. As a result, many of these appointed council members were forced to go underground.

The Erdogan government aims to revive this original plan now that Damascus is under the control of HTS, which has long been collaborating with the Turkish intelligence agency, securing funding and supplies through the Turkish-Syrian border for years. The public display of Turkish intelligence chief Ibrahim Kalin with HTS leader Al-Julani in Damascus and praying together at the Umayyad Mosque marks a visible symbol of this years-long, covert partnership between MIT and HTS.

In areas already under Turkish army control, the Erdogan government has pursued what some have called a “Turkification” project, changing the names of roads and public squares to Turkish and Ottoman names. For example, Afrin Square was renamed Recep Tayyip Erdogan Square and the public park in I‘zaz was renamed Ottoman Nation Park.

The school curriculum in these areas have been heavily influenced by Turkey’s Ministry of National Education, with a revised history of Syria under Ottoman rule. Turkish public universities have established local campuses, and higher education in these regions is now connected to the Higher Education Council in Ankara. Moreover, Turkish cultural centers have been set up to teach the Turkish language, culture and history to the local population.

At the same time, the Erdogan government introduced the Turkish lira as the currency for market trade, replacing the Syrian pound. Turkish state banks opened local branches and Turkey’s postal service, which manages both letter and parcel distribution as well as offering financial services such as wire transfers, also established offices in these areas.

Furthermore, Turkish government officials established civil registry authorities to oversee services provided to the local population in these areas and replace Syrian-issued records. Even identity documents were issued by the Turkish government. Judicial matters were also partially managed by Turkey. In Afrin, for example, a local court was redesigned to accommodate a Turkish public prosecutor sent from Turkey.

The display of Turkish President Erdogan’s picture in the offices of official buildings has become a common occurrence. Erdogan’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has also established local offices in these areas.

The Erdogan government has also been accused of altering the demographic composition in areas under Turkish army control by forcing the departure of those perceived as disloyal to Turkish rule. Meanwhile, displaced people from Turkey and other parts of Syria have been brought in to settle in areas vacated by those who fled the region out of fear of Turkish rule or were coerced into leaving under threat.

The Turkish government’s Directorate for Religious Affairs (Diyanet) has also established its presence in Turkish-controlled areas, training and recruiting imams who adhere to Muslim Brotherhood ideology as well as other radical jihadist ideologies. The mosques in these areas are managed by individuals vetted and approved by the Diyanet.

In a relatively small area close to the Turkish border, Turkey may have succeeded in creating an image of itself in northeastern Syria. However, replicating this on a larger scale to encompass all of Syria is no easy task and risks provoking significant resentment and strong pushback.

In any case, stabilizing Syria will require Turkey’s cooperation with Syria’s neighbors, regional powers and key international players, including the US, UK, European Union, Russia and China. If a grand bargain among these parties is not reached and Ankara insists on pursuing this alone, Syria could face another decade of violent clashes, rebellions and armed conflict.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.