Jesse Jackson

March 14, 2018

Donald Trump is taking a lot of heat for his snap decision to talk face to face with Kim Jong-un of North Korea. His aides caution that the meeting may never take place, that concrete conditions must be met for it to happen.

Conservative pundits and foreign policy pundits fret that Trump has given Kim recognition that North Korean dictators have sought for decades in exchange for a mere promise to pause missile and nuclear tests. Republican Sen. Corey Gardner calls for “concrete, verified steps towards denuclearization before this meeting occurs.” Even Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren describes a face-to-face meeting as “a win for them. It legitimizes, in their view, their dictatorship and legitimizes their nuclear weapons program.”

Admittedly, President Trump’s sudden agreement is a head-spinning reversal of direction from schoolyard taunts and threats of war to an agreement to meet and talk. But I would rather Trump and Kim talk to each other than threaten each other with war and nuclear weapons.

It may be that Kim craves the recognition and Trump the flattery, but these caricatures are irrelevant. Whether they agree to agree or agree to disagree, their meeting can make war less likely. I have always believed that one can talk without conditions toward an agreement with concrete and verifiable conditions. The notion that Kim will give up his nuclear weapons program as a precondition to any talk is nonstarter, a recipe for increasing tensions and escalating crisis.

It is time to get real. North Korea is a dictatorship and an impoverished country, crippled by a failed economic system and harsh international sanctions. It is also a nuclear power, in possession of 20 to 60 nuclear weapons. It has sustained its nuclear weapons program in the face of immense international pressure.

After George Bush named it part of the “axis of evil” with Iraq and Iran, North Korean leaders had every reason to believe that nuclear weapons – and their ability to destroy South Korea’s capital with conventional weapons – were essential to deter any attack on them. Kim no doubt noticed when the U.S. and its allies took out Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi after he got rid of his nuclear weapons.

There is no rational military “solution” to North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. An attack by the U.S. is unimaginable, with millions of lives in South Korea at risk. Threats and juvenile taunts about having a bigger nuclear button only ratchet up tensions. Escalating and ever more aggressive military exercises only increase the possibility of a war by miscalculation.

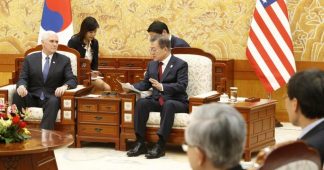

This opening comes from the initiative of South Korea’s president, Moon Jae-in, who has worked tirelessly to lessen tensions between North and South and to broker a meeting with U.S. and North Korean officials. He embraced North Korea’s participation in the winter Olympics. Kim sent his sister with an invitation to a summit.

While Vice President Mike Pence startled Koreans with his lack of manners and hard line at the Olympics, President Moon responded positively, dispatching envoys to North Korea to continue the talks and begin to arrange a summit. At that meeting, Kim stunned the diplomats by saying that he was open to talking with the Americans about his nuclear program, willing to suspend nuclear and missile testing to open the way for talks without insisting that the U.S. and South Korea suspend their joint military exercises that have always been a source of tension.

This caught the U.S. by surprise. We have no ambassador in South Korea. The State Department’s top diplomat in charge of North Korea policy, Joseph Yun, recently retired. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson was essentially out of the loop when Trump made his snap decision to agree to a meeting.

Can the talks take us from the edge of co-annihilation to the possibility of co-existence? That’s surely unknown. The hermetic kingdom of North Korea is one of the most closed countries in the world. It is separated from the world by a wall, so it lives in the shadows, which allows propaganda, fear, lies and rumor to define reality.

It will take more than one summit to resolve this crisis. South Korea’s president will meet with Kim before Trump does. Trump and Moon would be wise to suspend this spring’s U.S.-South Korean military exercises unilaterally, as a gesture of good will before the talks.

Any agreement will meet formidable obstacles. Could an agreement be verified, given North Korea’s fear of outside observers? Will the U.S. and its allies ease sanctions if Kim agrees to discontinue nuclear and missile tests, as a first step toward peaceful relations? What would be necessary to make North Korea confident that they won’t be attacked if they disarm?

One thing is clear. It is far better that Trump and Kim are moving toward talks rather than escalating threats. Negotiations are preferable to name calling and missile rattling. Trump’s decision to accept Kim’s offer was characteristically impulsive, abrupt and unbriefed.