By Julian James and Kate Randall

11 April 2020

The death toll in the United States surpassed that of Spain on Friday, with more than 18,400 fatalities recorded. For the first time, the daily death toll exceeded 2,000. Over the past three weeks, 16.8 million Americans have filed for jobless claims in the largest and fastest wave of job cuts on record.

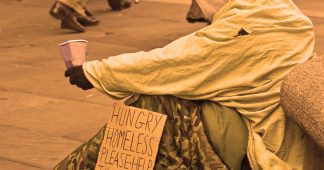

Workers who have been laid off or furloughed are facing the very real prospect of hunger. With supermarket shelves emptied of staples and cupboards increasingly bare, people are lining up in record numbers at food pantries across the country.

In San Antonio, Texas on Thursday, traffic stretched for over five miles as cars lined up for a food distribution organized by the San Antonio Food Bank at Traders Village. Six thousand converged for the giveaway, with some arriving over 12 hours early to make sure they received food.

Four hundred volunteers gave out 200 pounds of food per car, including fresh fruit and vegetables, frozen chicken and pork, and Easter candy. “We have to do this to survive,” Albert St. Clair told NEWS4SA.”

On Facebook, organizers posted the comments of one of those who came. “Since the coronavirus hit, it is hard to find food,” Ms. Honore said. “Seniors need to eat too. The food is scarce and it’s getting more expensive.”

Charitable food distribution organizations are being overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The current outbreak, aside from directly threatening the lives of those who contract the virus, is rapidly impoverishing many hundreds of thousands if not millions of people. At the same time, shortages of manpower and logistical challenges are overwhelming the ability of food distribution organizations to provide assistance. There is a serious danger of a dramatic reduction of access to food and levels of hunger not seen since the Great Depression.

Also on Thursday, hundreds of Los Angeles residents lined up for free food handed out by the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank. Several tons of shelf-stable food, frozen meat and fresh fruit were distributed to families impacted by the city’s collapsing economy, mass layoffs and reductions in work hours. The food bank says the distribution will be enough to keep families going for a few days but is uncertain what resources will be available in the future.

On March 30, hundreds of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania -area residents waited for hours, beginning at 7 a.m., in a mile-long lineup of cars to receive two boxes of food being given out by the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank. Aerial footage was shot showing hundreds of cars waiting in line to access food bank supplies in the city. Pittsburgh has seen food bank usage increase by 543 percent in recent days.

Chronic hunger, exacerbated by the pandemic, has been a decades-long problem for the American working class. In 2019, the US Department of Agriculture reported that more than 37 million people—over 10 percent of the population—faced difficulty obtaining enough food. Those most likely to face hunger were households with children, with an estimated 11 million children classified as food insecure.

The scourge of hunger is felt in every geographical region, though it is especially acute in the South, the Deep South, the Southwest and Alaska, compounded by state governments with onerous restrictions on who can receive aid.

In Palm Beach, Florida, a four-minute drive from President Trump’s private Mar-a-Lago resort, the kitchen staff at Howley’s Restaurant have been cooking free meals for the thousands of workers from Palm Beach’s closed restaurants and resorts. Rodney Mayo, whose 17-location Subculture restaurant group owns Howley’s, started handing out brown-bag lunches and dinners from the diner’s parking lot on March 21, having had to lay off 650 workers the day before. The restaurant group gave away 15,000 meals in the first 10 days.

Hillary Gale, spokeswoman for Feeding South Florida, said in a statement, “Normally we serve around 706,000 food-insecure folks throughout the quad-county [from Palm Beach to Monroe counties] and we are seeing a 600 percent increase due to COVID-19.”

At least 100,000 people have filed for unemployment in Alabama since the pandemic began. The Food Bank of North Alabama reports that three times the normal number of people are getting food from the organization.

Shirley Schofield, executive director of the food bank, told local media, “We have spent about $130,000 just on food alone. That doesn’t count any of the fuel of the trucks or the people to distribute the food. That’s just in the past few weeks. Normally it would take us six months, or a quarter of a year, to spend that money.”

The tens of millions of families that rely on food banks and other charitable organizations to bridge the gap are now faced with reduced access to one of their only lifelines. While food banks and similar programs are reporting an average increase in usage of 40 percent, the need has grown far greater in some areas.

Problems related to the sudden surge in demand are being compounded by a host of other difficulties arising from the pandemic, including increased retail purchases of non-perishable foods, which normally make up the bulk of food assistance. Shelves are bare in stores that previously donated excess products to food pantries.

The ramped-up demand at supermarkets has also resulted in food manufacturers reducing their donations to hunger relief organizations. As a result, pantries have been forced to increase direct purchases of food, draining their budgets while they wait for supplies from the Emergency Food Assistance Program, which received a funding increase from two recent federal “rescue packages.”

Another problem hindering food distribution organizations, like the country’s hospital and transportation sectors, is a critical lack of manpower. Finding enough volunteers to staff food banks and other programs is becoming increasingly difficult due to safety measures and increased need.

The highly contagious COVID-19 virus has forced operations to adopt social distancing measures, thereby changing how food is distributed. Instead of clients entering food banks to select items themselves, many of those seeking relief must now drive up to the distribution point with their trunks open, resulting in hundreds of cars waiting in line for hours.

This, in turn, requires traffic control and the sourcing of new sites suitable for such an operation. Staff must also pre-assemble the boxes to minimize human interactions and ensure social distancing, which takes time and labor.

At the same time, staffing levels are down overall due to illness, unemployment, insufficient personal safety equipment and a sudden lack of childcare as schools are closed. In Pittsburgh and other locations, including Louisiana, some food kitchens are now relying on the National Guard to continue providing services. In other areas such as Central Florida, dozens of feeding programs have been shut down due to a shortage of manpower.

Feeding America, a private network that operates 200 food banks and 60,000 food pantries and meal programs across the US, estimates that $1.4 billion will be needed to feed America’s hungry during the coronavirus pandemic. Should the state shutdowns last for months, the need for food assistance will rise.

Claire Babineaux-Fontenot, CEO of Feeding America network, recently appeared on Fox News to appeal for donors, stating, “I have never had an awareness of anything so jarring, so replete with challenges as what the charitable food system is facing right now, and that’s because of what it means for people who are facing hunger… The people who are showing up, so many of them, are people who have never needed us before… People who never dreamt they would need the charitable food system to feed themselves and their family are showing up.”

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos announced last week that he would be donating $100,000 to Feeding America. This paltry sum is an insult to both America’s hungry and the nation’s grocery and delivery workers, who are risking their lives working with little protection during the pandemic.

Bezos, with a net worth $117.2 billion at last count, has treated his own employees at Amazon and Whole Foods with contempt, forcing them to work with little protective equipment alongside coworkers who have tested positive for COVID-19. Testing has been denied. Amazon workers have joined Instacart and other delivery workers in walkouts to protest these unsafe conditions.

Snapshots of food banks across the country give an indication of the extreme need facing families:

- In Maine, the Good Shepherd Food Bank helps supply 450 partner food pantries across the state, serving about 178,000 people a year. Since the COVID-19 crisis, need has doubled, but donations are down 70 percent.

- In the Milwaukee, Wisconsin area, the Hunger Task Force has instructed food pantries to reduce how much they provide. Beginning in March, pantries were encouraged to provide customers with two weeks of food. That is now down to 3–5 days a month.

- In Omaha, Nebraska, donations for March to the Food Bank for the Heartland dropped by nearly half. The food bank, which typically purchases $73,000 of food in a month, has spent $675,000 in the past four weeks.

- In Seattle, Washington, where the outbreak in the US began, independent food bank Northwest Harvest estimates that Washington state has gone from 800,000 people struggling with hunger to 1.6 million since the crisis began.

- In New York City, the current global epicenter of the pandemic, a little over a month since the first case of COVID-19 was detected, Hunger Free America says that about one-third of the city’s food pantries and soup kitchens have closed. City Harvest reports that 74 of the 400 soup kitchens, food pantries and other food programs across New York’s five boroughs have shut down, due either to precautionary measures or a lack of staffing, as volunteers stay home for fear of contracting the coronavirus.