The U.S. military is more than capable of establishing one, but the endeavor is expensive and resource-intensive—diverting energy, capacity, manpower, hardware, and intelligence from regions deemed higher priority for the United States.

March 9, 2020

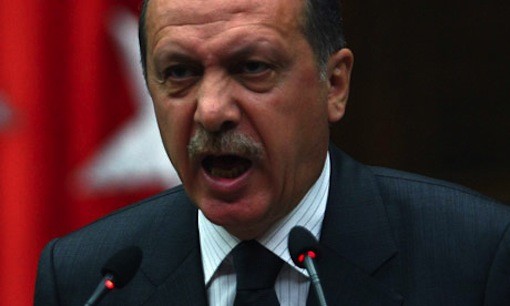

After six hours of talks on the Syria conflict last week in Moscow, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan came away with a deal. The Assad regime and the jihadist-dominated opposition in Idlib would follow a cease-fire, a buffer zone—jointly patrolled by Russian and Turkish forces—would be established to the north and south of the M-4 highway, and the frontlines would stabilize for the time being. The agreement is nothing but a band-aid, a pause in the Syrian army’s operations and a way to temporarily forestall a rush of another one million Syrian civilians into Turkey.

Truce or no truce, the massive displacement of Syrians in Idlib since December has resurrected an idea in Western capitals that has never really died: the safe zone. Protecting Syrian civilians from the Syrian Air Force remains an intoxicating option presented by its advocates as the only way to prevent an end-of-war bloodbath.

Like a moment of a deja-vu, the safe zone option is reappearing in the public sphere. Former U.S. Ambassador to Syria Robert Ford proposed a modified version of the old idea in Foreign Affairs last month, writing that “The best option…is a safe zone located on the Syrian side of the Turkish border that is defended by Turkish artillery, missile, and antiaircraft systems located on the Turkish side of the border.” German Chancellor Angela Merkel brought it up on the eve of an EU foreign ministers meeting last week, saying a zone of protection for civilians would be “helpful” if it could be negotiated. Merkel’s own defense minister backed her up, suggesting a European-patrolled zone would be the ideal way to make it a reality.

This, of course, is hardly the first time a safe zone or no-fly zone has been put forth as a solution. The concept is as old as the civil war itself.

Former Sen. Joe Lieberman called for a safe zone in the fall of 2011, only a few months into the violence and months before Syria was carved up between the regime and the opposition. After the Assad regime began leveraging its air power on the opposition, the Obama administration actively studied the proposal with Turkish officials in the summer of 2012.

The late Sen. John McCain took to the CNN airwaves in 2013 to openly lobby for a U.S.-enforced protected area, asserting that “we should be able to establish a no-fly zone relatively easily.” The Washington Post editorial board expressed its interest in the idea a year later, explaining that such a policy would not only be a course correction to the Obama administration’s previous failures in the country but would also provide Bashar al-Assad’s political opponents with the space inside Syria to build a new regime. Then Democratic presidential candidate and former secretary of state Hillary Clinton wasn’t far behind, telling the Council of Foreign Relations in October 2015 that a U.S.-imposed no fly zone would give Washington “extra leverage” with Moscow in discussions to get Assad to the negotiating table.

Foreign policy heavy hitters like former U.S. ambassadors Nicholas Burns, James Jeffrey (currently the Trump administration’s Syria envoy), former NATO commanding officer Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, former senior State Department adviser Fred Hof, Brookings Institution senior fellows Robert Kagan and Michael O’Hanlon, and former U.S. Ambassador Samantha Power have all supported the imposition of a no fly or safe zone at one time or another. It’s a popular option among mainstream foreign policy hands because it’s so appealing: who wouldn’t want to defend Syrian civilians from a criminal regime that uses its own air force to lay waste to hospitals, markets, homes, and entire cities?

And yet the risks of initiating such a zone are even higher today than when Gen. Martin Dempsey, a former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, briefed lawmakers about it in 2013. With Russia and the Assad regime controlling the airspace in Idlib, Washington would have to either receive Moscow’s permission to fly in the area (it’s inconceivable Russia would accede to such a request) or be willing to accept the possibility of engaging Russian fighters in highly combustible airspace. While pundits tend to be confident that Moscow wouldn’t dare challenge U.S. pilots, the scenario is real enough for U.S. policymakers to avoid it. Nobody wants an accident, miscalculation, or dogfight between the world’s two largest nuclear weapons powers, particularly over a stretch of territory in Syria that is as much of a lost cause as Idlib.

The practicalities of a no-fly or safe zone aren’t to be dismissed either. The U.S. military is more than capable of establishing one, but the endeavor is expensive and resource-intensive—diverting energy, capacity, manpower, hardware, and intelligence from regions deemed higher priority for the United States. Neither the Obama or Trump administrations have been willing to make that investment when U.S. national security interests in Syria are so limited. To put it in as logical a way as possible, Washington has bigger fish to fry.

The violence in Idlib has gradually tapered off due to the Russia-Turkey mediated truce. But nobody who has watched this nearly decade-long war will tell you that the truce is going to stick over the long-term. When it’s convenient, the Assad regime will resume its offensive in the province—and Moscow will back up Damascus, using the presence of jihadists as justification for reneging on its earlier agreement.

None of this, however, will make the option of a safe zone any more palpable.

* Daniel DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities, a foreign policy organization focused on promoting a realistic grand strategy to ensure American security and prosperity.

Published at https://nationalinterest.org/blog/skeptics/syria-safe-zone-idea-back-and-it-still-wont-work-130942