The internet, from its inception, was created as a tool of mass surveillance. Yasha Levine traces the origins of the web in his book, and how its roots in counter insurgency shape its function today.

Chris Hedges

Apr 03, 2025

Transcript below

The internet, from its inception, was created to be a tool of mass surveillance. It was developed first as a counterinsurgency tool for the Vietnam War and the rest of the Global South, but like many devices of foreign policy naturally it made its way back to U.S. soil. Yasha Levine, in his book Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet, chronicles the linear history of the internet’s birth at the Pentagon to its now ubiquitous use in all aspects of modern life. He joins host Chris Hedges on this episode of The Chris Hedges Report to explain the reality of the internet’s history.

Levine describes the early concept of the internet as “an operating system for the American empire, an information system that could collect all this data and that could provide useful, meaningful information to the managers of the world.”

This was understood by university students with close proximity to the internet project as well as domestic critics. Far from its coy, modern day interpretation of the internet as a mere communication technology, Levine makes clear the originator’s plans as well as the surprising resistance to them that followed. Levine explains that at the height of the Vietnam War, when much of America’s youth were protesting and seeking to understand the American empire, people were aware of the large amounts of capital it took to purchase and run computers, capital that only the most powerful in America had access to.

“This history or this understanding [was repressed] and people have been propagandized to view computers in a totally different light, in a benign light, in a utopian light, which was not the case in the 1950s, in the 1960s, in the 1970s and even up into the 1980s,” Levine tells Hedges.

Today, the internet’s omnipresence vindicates the skepticism of those early skeptics. Even the supposedly privacy-advocating technologies developed in response to the internet project, Levine explains, came out of the Pentagon for military purposes. Levine reveals the Tor browser, Signal messaging app and other tools that were meant to help ordinary people hide themselves from American surveillance spies were actually developed to help the spies these same applications claim that they are subverting.

“Jacob Appelbaum and Roger Dingledine, who was also the head of the Tor project back then…these guys were on the payroll of the US government.”

Transcript of video

Chris Hedges

Yasha Levine in his book Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet documents how the internet, from it’s inception during the Vietnam war when its early prototypes were designed to spy on guerrilla fighters and antiwar protesters, has always been designed for mass surveillance, behavior tracking and profiling. Its evolution spawned the massive private surveillance industry that lies behind tech giants like Google, Facebook and Amazon, which not only mine our private information for profit but share it with the government. The military, intelligence agencies and Silicon Valley, he argues, have now become indistinguishable. Everything we do online leaves a trail of data.

Google pioneered this collection of our data for profit, but it was soon copied by a host of other digital platforms including Facebook, Apple, eBay, Netflix, Uber, Tinder, Four Square, Twitter or X, Instagram, Angry Birds and Pandora. We are the most watched, photographed, monitored, tracked, profiled and surveilled population in human history. Nothing is private – our personal and business correspondence, financial documents and bank statements, arrest records, medical history, vacation photos, love letters, sexual habits, marital status, ethnicity, age, gender, incomes, political positions, shopping receipts, locations, text messages, school records, anything sent and received by email.

This vast trove of personal data in the hands of corporations and security agencies, such as the FBI and the NSA, presages a terrifying dystopia. For when the government watches us 24 hours-a-day we cannot use the word liberty. This is the relationship between a master and a slave. Joining me to discuss his book Surveillance Valley: The Secret History of the Internet is the investigative journalist and founding editor of eXiled Yasha Levine.

There were a lot of things I learned in this book that I didn’t know. It’s a great history. The first thing I didn’t know is that this had its origins in the Vietnam War. So I want to talk about where we are now, but maybe you can give us a sense of the evolution of the internet and how it was always tied to the surveillance state in the military.

Yasha Levine

Yeah, thanks for having me on. Yeah, well look, I mean, I think a lot of people don’t really realize that surveillance and influence, these are features that didn’t just come to the internet recently, or even 10 years ago, or even 20 years ago when this technology first started kind of gaining traction. These functions, these features of this technology were built into the technology. I mean, they were the reason why they were created. And to understand that, I mean, we have to go back to the 1960s and to the 1970s and really, to a kind of a new post-World War II world order where America was a global power.

It wasn’t the only power it was facing off against the Soviet Union. Communism was a perpetual threat to the foreign policy establishment, to the business establishment of America. It was like the obsession, right, of the Cold War obsession. But there was a problem in that a lot of the conflicts that America suddenly faced especially after the Korean War, were not wars where big armies were facing off against each other. These weren’t like tank battles. wasn’t like troops marching in formation or anything like that. These were smaller wars, basically wars of liberation, of third world liberatory wars where local populations were essentially rising up against their colonial overlords. And the U.S. was usually aligned with the colonial overlords of these countries or backing them or these were puppet regimes in some cases that were directly backed by either the old European colonial powers like France in the case of Vietnam or America itself in South America.

And so you have these populations, they’re distributed populations all around the world. They’re fighting wars that are kind of specific to their location. A lot of the fighters aren’t in uniform. They’re actually part of the civilian population. They are the population. And so what a lot of—there was a new kind of way of thinking about how to fight these wars and it was essentially a new doctrine, a counterinsurgency doctrine that was emerging in the 1960s.

And it was the sense that we really can’t fight these wars without understanding the population that we’re dealing with. Why are they rebelling? Why are some people rebelling and other people are not? What can we do to convince maybe in a soft way with aid or with other kind of economic programs to tamp down dissent?

And if that doesn’t work, what kind of more tougher measures can we take in order to put down these uprisings? And so the internet came out of a very specific program that was initiated by a very new agency called ARPA, the Advanced Research Project Agency, which was actually ARPA started out as a kind of pre-NASA agency that was then defunded and then reconfigured into a counterinsurgency agency under John F. Kennedy under his administration.

And it was essentially let loose on the Vietnam conflict to figure out new technologies and new methods of trying to win this war in Vietnam. And so the agency did a lot of different things. For instance, it developed drone technology to figure out how can we more effectively surveil the jungles. You know, it developed Agent Orange. How can we prevent sort of the guerrillas that are attacking French and American troops from using the jungle as cover, right, for their kind of raids.

And so, and part of that was also developing new ways of studying the Vietnamese population, its habits, its beliefs, its spiritual ideas to try to figure out how to pacify these people using psychological techniques and things like that. So ARPA funded all these anthropologists essentially to go out into the field and collect data. And there was so much data coming into the Pentagon from that that there really wasn’t a way of keeping it in one place to make it useful. So that was one thing.

So there was a need to create data systems that could manage all this, what was essentially surveillance data of these populations, right? And to process it, to extract something useful out of it. At the same time, ARPA was involved in a kind of a surveillance system in a different way. It was trying to track the movements of Vietnamese fighters on the Ho Chi Minh trail. Again, they were using jungle cover to hide massive movements of troops, of supplies and things like that.

So they were trying to develop basically like spy devices that could listen, that could be dropped from the air, that could listen to what was going on in the ground under the jungle cover, that could even smell human urine. If there were fighters peeing in the jungle, it would detect the urine and send a signal to base and then that location would be bombed from air.

So there are all these different surveillance things that was involved in that were very practical to fighting the Vietnam War. But at the same time, there were people in America, in back of the United States that were thinking on a kind of a bigger scale that were seeing, that saw America as a global power. And you really can’t be a global power in the modern age, overseeing all these vast different conflicts without having some kind of bird’s eye view of the entire globe, of knowing what’s actually happening in the world.

What are people talking about? What kind of political movements are sort of brewing in the various different locations in which America has an interest? And so they started kind of thinking about creating a, I don’t know, to use today’s terms, like an operating system for the American empire, an information system that could collect all this data and that could provide useful, meaningful information to the managers of the world.

So it was a kind of bureaucratic view of the American Empire. And so these things essentially kind of merged together, these different streams merged together, and they birthed the ARPANET and various programs that were associated with the ARPANET. The ARPANET was this network technology that could connect different kinds of computers together in one network, where information could be shared amongst them.

That was one part of it. The other part of it was to actually create computers that normal people could use. So people don’t really know, but the operating system that we use here, I have an Apple Macbook here, the graphical user interface, the mouse, all these things, the menus, the drop down menus, all these things were actually developed by the military as part of the ARPANET program.

So part of it was to create this network that could connect computers, but also to create a new type of computer that could be easily used by regular people, not engineers, because before this kind of graphical user interface that we’re all used to, computers were punch cards. You needed these technicians who would punch in data on these punch cards. They’d feed it into these vast computers, and then they’d produce some kind of data. So they were more like complex calculators rather than machines that you could interact with that you could actually interface with in a natural way.

And so that’s the origin of it. I mean, the origin of the internet was about fighting insurgencies, about studying foreign populations, but also creating a platform that would allow America to run the world and to see the world, to make it transparent.

Chris Hedges

Well, let’s talk about its domestic use, because it wasn’t just used on fighters in Vietnam. It was used on anti-war activists in the United States.

Yasha Levine

Yeah, I mean, look, you know how it is. Anything that you deploy for use abroad, it immediately gets imported back into for domestic purposes, right? So almost immediately, this ARPANET technology was used to ingest information about activists against the Vietnam War specifically. What’s interesting is because a lot of the research that was part of the ARPANET program that created the internet was done at universities, students actually knew quite a bit about these things, even in the late 60s.

Chris Hedges

Well, you talk in the book about, I think it was students at Harvard and MIT who saw where this was going and publicly protested.

Yasha Levine

Yeah, I mean, look, it was interesting to me writing this book and researching this book because I went into the archives at MIT, at Harvard, and looked at various declassified documents. And what was amazing to me is that students from the Students for a Democratic Society at Harvard and MIT had a more complex and sophisticated critique of internet technology or network technology than people did in the Obama era. Right?

Because I was writing this book at the tail end of the Obama era. And so people still viewed internet technology as a liberatory technology, as a democratic technology, that the internet would create this global democratic village. I people still believed that back then. People don’t believe it so much anymore. Maybe we can talk about that a little bit later, why that is. But back then, you know, not that long ago, people really did believe in the liberatory power of the internet.

Meanwhile, of course, the internet is owned by these massive corporations, some of the wealthiest corporations on the planet. Of course, they work with the NSA, with the CIA, with the FBI. I mean, the relationship has been intertwined from the very beginning. But people believed it, right? People believed the kind of the marketing mythology that these internet companies have pushed as part of their product. But in 1969 and 1968, when the first links were activated, of the ARPANET links, the first nodes were starting to work together, already students at these universities were protesting them.

They were producing these very sophisticated pamphlets trying to educate other students and other people about the danger that these technologies pose. And they said it outright. They said, look, these computer technologies, these network computer technologies that ARPA is trying to create are tools of surveillance. They’re tools of political control.

They’re designed to basically pacify political movements abroad and are designed to pacify political movements at home. I mean, there was an incredible pamphlet that I discovered in the archives at MIT. So because it was clear back then, I think, to people who were watching the emergence of computer technology that computers were linked with power because computers were controlled by major corporations.

They were very expensive to purchase, they were very expensive to run, and government agencies. So back then, people understood it wasn’t an epiphany or anything like that. People understood that if you own a giant IBM computer, you’re using it to crunch data, you’re using it to crunch numbers, you’re doing it to kind of extend the power over the organization that’s using it, right? It’s an extension of their power.

And that the only people who could afford to use these things were very powerful entities in American society. And so the linking between power and computers and control and influence was obvious to, I think, even in the mainstream, in the American mainstream, I mean, you had like magazines like The Atlantic or something, you know, doing front page stories about how computers are agents of surveillance and control and things like that.

So it was understood back then. And essentially it has been forgotten. It was repressed, this history or this understanding, and people have been propagandized to view computers in a totally different light, in a benign light, in a utopian light, which was not the case in the 1950s, in the 1960s, in the 1970s and even up into the 1980s, people still viewed computers with skepticism. I think things started to change in the 1990s when things started to get commercialized.

Chris Hedges

Well, you talk about that and that was a very conscious effort to rebrand the internet. It wasn’t an accident. But before we go on to the commercialization of the internet, I just want you to talk about what it was these computer systems, you talked a little bit about that in Vietnam, but let’s talk about like the anti-war activists. When I covered the war in El Salvador, they were using this system. And anecdotally, I heard that they knew the names of every fighter in every single tiny guerrilla unit. They had charts and where they were from and this kind of stuff. But talk about the exercise of that knowledge and power.

Yasha Levine

I mean look, there was a series of scandals in America during the Vietnam War era where it was found out that the US Army was essentially running one of the most massive surveillance operations in the history of America. It’s probably been eclipsed now with the internet because the internet just automatically collects so much data.

But back then, to collect data, you really needed to put people out in the field. And you needed to create files. People had to really, you needed to have manpower to do this stuff. So they came up with… You probably remember this stuff. They posed as fake camera crews that would go and film, cover anti-war protests. And then they’d actually produce reels.

Chris Hedges

Well, you write about this in the book. But I mean, but you also noted that they were sending all this back to where was it? The Pentagon or somewhere or the NSA. But as you said in the book, they could have just watched the evening news.

Yasha Levine

Exactly. I mean, essentially the generals in the Pentagon had their own private TV network that was creating newsreels for them. But, look, I mean, so surveillance was happening, right? But what I think, there was a major escalation with this technology, with the ARPANET technology and the ability of these new computers to ingest data and to make it accessible. That’s the key, right? Because you can have a lot of data. It’s stored somewhere on paper or in these punch cards. And really, if you’re trying to get at, trying to study some kind of political cell in, let’s say, yeah, Nicaragua or Ecuador, if you’re trying to study those things, you really need to make it accessible to regular people who are staffing the Pentagon or the CIA.

And so I think what was the major escalation with this technology is that you could take all that data that’s being collected on, let’s say, it’s anti-war protesters or political movements abroad, and you could ingest it, and you could put them in essentially like an Excel kind of format, right? Like a database where things could be collated, things could be related, you could create relational maps between various individuals, all these things.

So suddenly that data isn’t just sitting somewhere and gathering mold in some basement, but it’s actionable, right? So it’s putting them at the fingertips of these bureaucrats wherever they are, whatever state security agency they’re in. And so I think that was the escalation. And there were some scandals where yes, it was even covered on TV.

It was a major scandal where there was even a whistleblower who notified the press that this new technology, ARPANET technology was being used to digitize old surveillance data on anti-war protesters and make it accessible not just to the US Army, which created it but share it with the FBI, with the CIA, with the NSA, and whoever, and even with the White House.

So the ARPANET almost immediately began to be used to spy on Americans. I mean, almost immediately. There was, I can’t remember the exact dates, I think it was 1972 or 1973, ARPANET came online in 1969. So just a few years after this experimental network came online, it was already being used to spy on Americans.

Of course, the Pentagon denied it, said it didn’t happen, that it was just an experimental thing and all this stuff. But the fact is that they did digitize surveillance data, illegally collected surveillance data, which the Pentagon was actually legally mandated to destroy. In fact, it didn’t destroy it, it digitized it and used this network to share it with all the security state agencies.

From the very beginning, again, I think this is what’s shocking to a lot of people who read my book, is that this wasn’t something that happened when Google emerged. This wasn’t something that happened with Facebook. This wasn’t something that happened with the NSA spying on us, as Edward Snowden revealed, tapping into all these internet giants. Surveillance was there at the origin of the technology.

Surveillance was the reason why it was created. just to give kind of an example, The first surveillance network technology was NORAD, essentially, right? So NORAD is this radar system that kind of watches the skies above the Northern Hemisphere or North America to watch for enemy bombers, specifically Soviet bombers, and to intercept them if they enter American airspace.

That was sort of why it was created initially in response to the Soviet Union also developing the nuclear bomb. And so that is a surveillance network. So you’re watching the sky, right? You’re looking for people who cross the border or who are coming close in the sky or the planes that are coming close. And that is what sort of the managers of the American empire were hoping to recreate, but on a societal level.

It’s an early warning system for political threats, essentially. That’s what this ARPANET project came out of. That’s the desire, that’s the dream, that was the wish, the Christmas wish of theirs. To create for societies what NORAD or air defense systems created for airspace. If you think of it like that, then the internet makes a lot more sense because the internet has created that reality.

We’re talking right now on this computer. I have my phone here. It’s always with me. It’s tracking me wherever I go. It’s a personal radar. It could be used to listen in on this conversation if it wasn’t public. We’re completely bugged. Everything like you said in your great introduction, everything that we do is surveilled. Nothing is unwatched and things could be correlated. Even if things that you don’t say, things could be inferred from your actions.

You know, one of the things that, I mean, even like, let’s say Google or Apple can even know that you had a one night stand purely by the movement of your, let’s say, mobile phone. It could infer a lot of things. It can infer who your friends are with, who you meet with. It can map out your social networks very easily. I mean, we are fully transparent in that sense, right? And so, but that idea that Google and Apple and all these tech companies really brought into being with the commercialization of the internet and the wide adoption of these technologies was there from the inception.

Chris Hedges

Let’s talk about that because that’s a big moment. So you commercialize the internet, but you have to shake that perception that it’s a tool of surveillance and that its roots lie in the military intelligence community. And I mean, that was a really fascinating moment in the book where in essence, they rebrand the internet as kind of part of the counterculture.

Yasha Levine

Yeah. Yeah, they rebrand the internet as part of the counterculture. And I think that rebranding even began in the 70s, really, because there were actually people who were hippies, who had long hair, who listened to The Grateful Dead and stuff like that, who were working as military contractors in places like UC Berkeley and a place like Stanford and a place like MIT, who were reading Lord of the Rings or whatever, walking around smoking dope, but yet building the surveillance technology for the military.

Even back then, they didn’t really see themselves as people who were doing a bad thing. They were just engineers who were creating a cool new technology. So there was that aspect of it even within the military industrial complex because a lot of the work wasn’t being done at the NSA or the US Army. People weren’t wearing uniforms, the people who creating the technology. They were engineering PhDs at universities.

So there was that aspect and so that aspect was essentially dialed up and expanded. I mean, I don’t know if listeners know who Stewart Brand is, he was a really big figure really in the 70s and 80s and 90s. And he was this pivotal figure who really helped almost like a doula or something. He helped birth this counterculture image of internet technology bringing it, connecting the kind of counterculture of the 1960s and the 1970s to the tech culture of the 1990s and beyond.

Like a big sign of that is let’s say, you know, Apple Computer. Apple’s Computer’s big ad campaign that it launched was all about fighting Big Brother. It’s kind of an iconic ad that people know about. Basically, the way that Apple computer was positioned was that by using this technology you could defeat Big Brother from 1984.

And there’s another thing that I think helped create this utopian image of the internet was that right as this technology was commercialized and was becoming cheap enough for people to buy, America won the Cold War. And so suddenly America was the global superpower. American ideology, American capitalism, new kind of technocratic capitalism that began to be global in nature and there was nothing opposing it from any other side and it was victorious and was dominant.

So the internet technology was being pushed as this new operating system for a new utopian kind of democratic global system, right? That if you allow this technology to spread all around the world, it’ll create, you know, a global democracy, a global democratic village. I mean, it’ll even make governments obsolete. You know, we don’t even need governments because people will decide things for themselves in this kind of anarchistic way, right?

We’ll just vote directly. We’ll talk to each other. I’ll talk to someone in Bangladesh, in Russia, in China, and we’ll all be these, you know, these, you know, perfect democratic voters, right? If we use these technologies, if we use these networks, if we use these computers like Apple computer or Windows or IBM or all these things, we use these technologies, we will be able to create a global unified society.

I mean, it’s within reach, you know, it’s a really a utopian idea. It’s a beautiful idea, I guess, but what’s unstated, right? What’s unstated was that all these technologies are run by American corporations, huge corporations that are not democratic that have their own interests in mind and that these corporations are very much in bed with the American empire there and completely intertwined with the NSA, with the Pentagon, with the CIA, with the FBI, these relationships with some of these companies go back decades and decades and decades like with IBM, for instance. IBM is essentially an extension of the American security state and had been from almost the very beginning.

Chris Hedges

Well, IBM, my uncle worked at Bletchley [Park], you know, breaking Enigma, then went straight to IBM because all of the military technology. They built the first supercomputer at Bletchley. He went straight to IBM and they just commercialized everything the military had done at Bletchley.

Yasha Levine

Totally, yeah. The computers that they built, let’s say for the first air defense system, were these giant IBM computers. For the time, they were super computers that were housed in these giant, giant concrete bunkers that were nuclear proof. Yes, IBM was very much intertwined with the American security state.

Chris Hedges

And I just want to interject, they were also intertwined with the Nazi death camps, which you talk about at the end of the book. They used the punch cards, used them completely. Yeah. The punch card system.

Yasha Levine

Yes, the Nazis used them. Yeah, they used the punch card tabulators to essentially find Jews and to more effectively exterminate them. But also, IBM is intertwined with the Social Security Administration. IBM essentially ran the Social Security program, right? So the welfare program, not the welfare, but the pension program of America, it was all done on IBM computers.

And so really IBM was like a privatized extension of the kind of almost like post-world war New Deal in a post-world war to American state and so I think the utopian rebranding I think depended on people being ignorant of actually what underlies the internet what underlies this computer personal computer revolution and what underlies it is American capitalism, right?

Chris Hedges

I want to talk about, before we get into Tor, I definitely want to, because you write a lot about Tor, and I want to get into the fact that these tech billionaires now have, you know, are essentially running rampant within the Trump administration. But just talk a little bit about what you call the censorship arms race. This is the early 2000s, because I thought that was a really important point.

Yasha Levine

Well, look, yeah, because while on the one hand the internet was being sold to American but also global consumers as this technology of utopianism and democracy, America saw the internet as a tool of American foreign policy and American power abroad.

Because America developed this technology and as it was sort of going outside of America and globalizing and being picked up in Europe, in Russia, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and in China as well, America, the State Department and CIA saw the Internet as like a crowbar or something that could, essentially, you could beam propaganda, you could use the internet to reach foreign populations in a way that you couldn’t before.

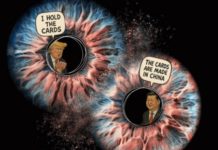

And so with China specifically, there began to be a conflict very early on in the 2000s about who gets to control your domestic internet space. China very quickly understood that the internet is a threat, that the internet is a tool of American power, and that if it didn’t control its domestic internet space, it left itself open to foreign influence from America and to various destabilization programs, propaganda and things like that. So China began to essentially control what gets past its national firewall, right?

And began to erect this kind of defense against unfiltered American internet content. Primarily a lot of these programs that were targeting the Chinese population were funded by the CIA or spin-offs from the CIA like Radio Free Asia and things like that. And so what that launched was America could not accept that. It could not accept that another country would say, look, we want to control what happens within our borders.

We don’t think that allowing CIA propaganda to just sort of target our population is good for us or is good for China. So we’re going to have a kind of censorship regime against the outside. And so America could not abide by that. To America, that was essentially like someone closing its markets to American corporations. China would not allow Google or other American companies to operate freely in China. And so the US began funding these kinds of anti-censorship technologies.

In the first iteration, the organization that was making these anti-censorship technologies, essentially tools that you could use to, that people in China could use, download to kind of go around the firewall. Initially, the main organization that was involved in that was Falun Gong, which is this pretty crazy right-wing occult that’s backed by the CIA that puts on all these sort of Chinese anti-communist ballets that you see posters for all over cities in America.

And this cult was creating these programs. But very quickly it moved to a different organization. And that organization was the Tor Project. That became kind of the major anti-censorship tool that America was promoting in China, but also in other countries like in Iran and then later in Russia.

Chris Hedges

Okay, explain what Tor is. It became the lodestar for WikiLeaks and for, I don’t know, do you call them crypto-anarchists? You know, these people who felt that they could evade surveillance through the dark web. I told you before the show, on Tor, when I was communicating after the Snowden documents, which were housed in Berlin, there was communication between myself and them, but they always insisted on doing it through Tor.

Explain what Tor is, explain what the dark web is, but as you also explain in the book, unless you are completely severed from Gmail and everything else, Tor, which I think by the end you make a very convincing case was always a fiction in terms of what it actually was, but also Tor becomes useless unless you completely sever yourself from all other normal internet activity but just explain all that for people who don’t understand what it is and how it works

Yasha Levine

Yeah. I’ll talk about first what Tor sort of says it’s going to do and then I’ll talk about the history because I think it’s very surprising about where the origins of Tor actually who created it and why it was created. So what Tor promises to do, you download, now it’s like a special browser. It’s essentially a kind of a different custom version of the Chrome browser, right? And that Chrome browser has a special program in it that what it does is it kind of does the, what do you call it?

Like the three-card monte, you know, it’s where con men on the street will try to play with you and you have to find where the little ball is underneath one of these cards. And so that’s what Tor claims it can do with your internet traffic. It obscures, it shuffles it around, right? Because, all right, the internet is fully transparent in the sense that when I go to, let’s say NewYorkTimes.com, right, I type into my browser NewYorkTimes.com.

That tells my internet service provider, hey, please request information from NewYorkTimes.com, the servers that have that information. So my internet provider knows where I’m going, what site I’m going to, what I’m requesting. And so whoever is watching my internet service provider, let’s say it’s the NSA or the CIA or the FBI or all three of them, know that this guy is requesting information from NewYorkTimes.com or Wikileaks.org.

And so it’s transparent to anyone who’s watching and to the company that provides the internet service. On the other end, my request is also transparent to the other internet service provider who is providing this information that hosts New York Times servers or WikiLeaks servers. So New York Times knows, hey, there’s a person from this IP address. They’re requesting this particular web page. Send it to them.

So my internet activity is transparent to anyone who has access to data that the internet service provider has access to. And so what Tor claims it can do, and it does do it, is to obscure kind of the origin and the destination of your internet requests. You request everything through Tor. So you request it through Tor and then Tor does this kind of shuffle with your traffic that no one really knows who you are. And so it sort of obfuscates your identity.

Chris Hedges

Well, you talk about how it became a tool for drug dealers.

Yasha Levine

Yeah, and then there’s another thing. It actually began to, you could host websites in like the Tor cloud essentially, which was the dark web. So you don’t actually ever leave Tor. So Tor is its own internal network essentially, and you never leave it. So if you request, let’s say, NewYorkTimes.com, it has to leave this Tor cloud because it has to go to the public website, internet.

But your identity, your entry point and your exit point are essentially broken up. They’re no longer connected. That’s what Tor does. Or you could stay inside that and host a website inside that and that was the dark web and it became very useful for pretty famous, yeah, the Silk Road, which is this big drug marketplace. The guy was caught eventually even though he used all these technologies. He, actually, Trump just pardoned him and released him from prison. He was serving two concurrent life sentences in prison.

Anyway, so that’s what it claims to do and it does do it on a technical textbook case. Yes, it does do it. The problem is that if you are using… Look, and if you’re using Tor to hide some kind of petty crime, let’s say, or you’re hiding from the local police or something like that, yes, it works. But if you’re using this technology to hide from the FBI or the NSA, it starts to fall apart.

And it was targeted that it could do that, that it could provide protection from the most powerful intelligence agencies on the planet. That’s sort of it’s stated, Tor itself did that, and the people who promoted Tor and backed it claimed that it could do that. The problem breaks because if you are someone like the NSA, you are observing vast amounts, you’re basically observing the entire internet in real time.

And the problem with Tor is that you could actually time things. So if you’re using Tor, it could time things. The amount of time it takes to jump through Tor is actually predictable. So you could say, this guy’s entering here, now here, and then someone’s coming out the other end a few milliseconds later. Well, we can correlate those together. So that was one way you could track people. Another way you could track people is that every computer and every browser has its own unique signature, which can also be tracked.

And then there’s just bugs in the code that are not known to people that the NSA has discovered and that has kept to itself, essentially allowing it to unmask people that way. There are all sorts of different ways to circumvent this. But there’s even a darker level to it, which I think makes it a lot more interesting. Tor itself, while it built itself as this independent agency that was run by these anarcho kind of crypto guys who hated the government, who had long hair, who seemed to be against the NSA, who were helping WikiLeaks and all this stuff.

Chris Hedges

You’re talking about Jacob Applebaum.

Yasha Levine

Jacob Appelbaum and Roger Dingledine, who was also the head of the Tor project back then, I don’t think he’s the head of it anymore. These guys were on the payroll of the US government, you know? And specifically nonprofits that were linked to the State Department and CIA spinoffs like the Broadcasting Board of Governors, it’s called a different name now, it’s called the US Agency for Global Media, I mean they use these, they pick these names, man, they’re like… you can’t remember them.

They’re just gray generic names and they keep changing them. But the Broadcasting Board of Governors back then was the umbrella agency that ran America’s government propaganda news divisions. Everything from Radio Free Europe to Radio Free Asia and all these different language programs that were targeting the Middle East, that were targeting South America, that were targeting China, Vietnam, Korea, Russia, Iran, blah, blah.

So just the entire American propaganda division that was sort of the agency that was overseeing it was also funding this supposedly anarcho, you know, sort of crypto spunky outfit that was going to protect you from the NSA. And also it had direct contracts with the Pentagon.

And the reason why the Pentagon was funding it, so all these different agencies that are funding Tor have different reasons why they were funding it. The reasons that the Pentagon was funding it was because it was, I think, it was being used by the US military actively. And the origins of the Tor project were actually in the US Navy, in the US Naval Laboratory. The US Navy is actually historically linked with surveillance and espionage.

Because historically, I don’t want to get into the details, but historically the US Navy was actually the driver of surveillance technologies and encryption technologies and interception technologies, basically to intercept signals intelligence that was coming from ships out in the ocean, right? And hiding its own signals intelligence from other countries. And so the US Naval Laboratory developed the Tor project or the technology that underpinned the Tor project to hide spies as they use the internet.

The problem with the internet is that it doesn’t matter if I’m using the internet, or if a CIA agent is using the internet, or an FBI agent is using the internet. We’re all transparent to the ISPs that provide the service. So if I’m a CIA agent and I want to infiltrate an animal rights forum or something like that or I’m an FBI agent and I want to infiltrate an animal rights forum. I don’t want the administrator of the forum to see that the IP address of the user that I created on that forum to be linked with Langley, or to be linked with an FBI office somewhere. I want to be able to hide that. So for an FBI agent to kind of use the internet, but to hide themselves in plain sight, they have to use Tor, or they have to use something like Tor. And so it was developed specifically to hide spies online, American spies online. That was the purpose of the project.

And the problem with this kind of technology is that you can also see that if someone uses Tor, because if you actually start tracing the IP information, you see that this user popped out of a Tor node or Tor cloud. And so in order for American spies to use Tor, they have to open to as wide an audience as possible, not an audience, but as wide a user base as possible. So everyone from criminals to drug dealers to drug users to, you know, let’s say political activists like Julian Assange to, I don’t know, soccer moms who are just paranoid about the government watching them or whatever. Like you want everyone to use it.

That way the spies can hide them in the crowd. It’s like in the old Cold War movies or something, you do the handoff in a crowded train station or whatever. You go to a crowded square to do the handoff where things can’t be traced as easily. And so Tor was created to hide spies, and then it was essentially handed off to this strange non-profit that was essentially run by these nobodies, people who were involved with helping kind of peripherally this technology but there were nobodies.

And suddenly it became this, it rebranded itself from a tool to hide spies into a tool that will help hide you from spies. So it did almost like a 180 right? It was a very interesting story, I don’t know will where else we can go from that or if this is enough because i want to get too much into the details.

Chris Hedges

Well, just quickly, because I want to talk about what’s happening right now in the Trump administration. But you argue in the book that Tor just ultimately doesn’t work. It can work.

Yasha Levine

I mean, I’d say it can, yes. It works on very low level cases, yes. If you’re hiding from just local cops or something like that, like petty crime, yeah.

Chris Hedges

Let’s talk about what’s happening now because Silicon Valley has now essentially come to power with the Trump administration. Let’s not forget they were all good liberals and Democrats until they weren’t. What are they doing? And talk a little bit about the AI projects. But I think people don’t quite understand what’s happening before our eyes.

Yasha Levine

Yeah, I mean it’s been interesting for me to watch this because when I was writing this book, in essence all the tech companies that were active at the time, Facebook, Google, Apple, Twitter, they really did not want to admit that they are part of the American empire. That they are completely embedded with the American state and especially with its foreign policy apparatus.

They really wanted to maintain that fiction. That, no, no, no, no, we’re just companies and we’re operating on a global scale and, right, yes, there’s these contracts, but they really would not answer questions about these things. They would not answer about the relationships or the active contracts that they had with the Department of State. I’m speaking specifically…

Chris Hedges

And Israel, let’s not forget.

Yasha Levine

And Israel, yes, and Israel was the kind of the quiet demon in the corner of the room. But America is an extension, I mean Israel is an extension of the American Empire, so it made sense that these tech companies and Israel are entwined. And in fact, Israel is such a big hub for computer technology that Google and all these different companies would actually buy startups that were created by people who came out of Israeli intelligence and all this stuff.

So there was the squeamishness about admitting that Facebook was essentially an extension of American power. That Google was a privatized extension of American power. Things have changed now, quite dramatically, I’d say. I’d say these companies are no longer squeamish about these things. They’re upfront about it. They’re very much more willing to talk openly about their patriotism, about how much they want America to succeed, and they are American companies, and they’re willing to take American security seriously and all these things.

And I think it’s had to do with, first of all, the maturation of these companies. These are pretty young companies. This whole sector really became big, look, it’s no more than 20 years old really, the economic power that these companies have. And the change in American politics and the collapse of this utopian technological mythology. Because I think it started to really turn during the first Trump administration and even in the run up to this Trump administration.

When I first saw sort of liberals really and Democrat parties start talking negatively about the internet is when they started pushing this idea that the internet is responsible for Trump’s victory, right, for why Trump is so popular. And not just the internet, but the fact that Russia and foreign powers are manipulating the American people into voting for Trump. So suddenly, you know, it really turned on a dime. Hillary Clinton, as the head of the Department of State under Obama, spearheaded her whole main policy as the person in charge of the Department of State, was the policy of internet freedom.

So she said that, no, countries cannot control their domestic internet space. They have to let America in, they have to let American companies in, and if they don’t let American companies in, they’re totalitarian, they’re anti-democratic, they’re thugs, they’re against freedom, they’re against liberty, they’re against everything that’s holy to us as democratic people. That was her whole thing that she was pushing in that position.

And then, of course, when she lost, she began to demonize the internet as this agent of chaos, as a dangerous technology. Because suddenly, whether it was real or not, she believed that the internet was used to subvert American democracy. I mean, I don’t subscribe to that theory, but that’s what she believed. So the internet started to be this agent of danger suddenly. So American society itself began to view, American elites really began to view the internet in a negative light. They no longer believed in their own mythology.

And so I think it started to really turn then. And because the foreign policy establishment, just the elites, began to turn inward much more and to begin to be, I don’t know, the idea that America would fully control the world in this kind global, neoliberal American utopia began to crumble and collapse. And so the mythology started to change. And so the American companies started talking a different way.

Now that’s a little bit different from part of your question about what these tech guys are doing with Trump and with AI. And I mean, I don’t know, it’s kind of a complicated question, I guess, because I think, I don’t know how you would look at it, but my sense of it is that it’s a full maturation of this industry, right? It’s kind of coming to its own in a way that it hadn’t really been before.

It’s now taking a kind of a leading role in shaping policies at the highest levels of American power. These companies are not ashamed to be public about their intentions and that they have so much… so it’s maturation, I think. Because they’re so intertwined with, specifically, the Trump administration. They really think that they have the money and they can influence the government to do things how they want them to be done, to install policies that they want. So they’re not like secondary actors anymore, they’re primary actors. And you can see it with the crypto stuff now where Trump has announced that there’s to be a strategic reserve of Bitcoin and all these other cryptocurrencies.

I mean, these are the express demands of the people who in large part funded his campaign. And so they are in power now. And so they are kind of bringing their ideology in a much more direct way to Washington.

Chris Hedges

Just in the last two minutes, what is it they want? What do they want to create that they don’t have?

Yasha Levine

That’s a good question, you know. I mean, I think they have everything they want. I’ll tell you what they want. They want… The crypto guys just want crypto to be fully basically deregulated and to be mainstreamed and to be made an official part of the American state. Almost like a secondary currency or something.

And they want access to government contracts. They want to be fully embraced by the American state. I mean they already have been, but they are much more open about it. I mean, think, look, I think they want power and they want a seat at the table. And they don’t want to be regulated. I think there are different factions. You know, I mean, if we’re talking about Elon Musk, I think he wants government contracts. He doesn’t want to be investigated for potential Wall Street fraud and all these things. But they just want a seat at the table like every other major industry like Wall Street or things like that.

Chris Hedges

But Elon Musk is talking about the everything app. I mean, they want to cut out banks. They want direct… I don’t want to use the word relationships, but they want to directly control everything that you do.

Yasha Levine

Yeah, they want to be the main monopolists. They want to be the middleman that funnel your life, the middleman for your entire life. I mean, and they are already that. I mean, this is what I mean. They already have pretty much everything they want. I mean, they’re integrated. I mean, if you take Elon Musk, he’s a military contractor. He runs one of the most important propaganda or one of the most media platforms, controls it, can silence whoever he wants or boost whoever he wants on his media platform.

He’s part of the surveillance state in a massive way. He’s fully integrated with both the kind of the media ecosystem of the American state, but also the security state apparatus. He runs a privatized NASA. He puts up spy satellites in the air. He provides spy satellite technology to the entire military establishment.

So he’s already fully integrated. I guess they just want more power and I think they want control. I mean, like to have a seat at the table in a way that I think, you know, Wall Street used to have, right? To be the drivers of policy rather than people who kind of lobby at the edges of things, you know?

Chris Hedges

Well, that’s what Yanis Varoufakis calls techno-fascism.

Yasha Levine

Yeah, they want to be the guys in charge, but they already are in charge. I mean, there’s just hubris, I guess, in a way. Because they are in charge, but they just want more and you can just see it. I mean, I think Elon Musk is such a distillation of their kind of insanity. It’s like you have everything you possibly want, but you actually just want more. You want more attention, you want more money, you want more control, and you want to be I don’t know, you want to be the king of America.

And he can’t be directly, I guess, because he can’t be elected. But he’s got the second best position now. We live in their world. I mean, this is… to close, I think it is important to think about the origins of internet technology. Because if you do look at the dreams that some people had that were involved in this stuff, we do live in their world now. Because the world that they envisioned was a world of technocrats managing the planet, right?

And overseeing a world where people’s desires are transparent, political movements are transparent, people’s obviously buying habits are transparent. Basically, that the soul of human society, writ large, sort of turned inside out and can be looked at and we exist in that. We exist in that world.

Chris Hedges

Well, it’s extinguishing freedom. I mean, let’s be clear. It’s the end of freedom. That was Yasha Levine on his book, Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet. I want to thank Thomas [Hedges], Diego [Ramos], Max [Jones], and Sofia [Menemenlis], who produced the show. You can find me at ChrisHedges.Substack.com.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.