On the night of December 2, 2017, a Honduran woman in the rural province of Olancho was protesting what she saw as a stolen election. The woman, eight months pregnant, stood in the streets in violation of a national curfew, and she screamed alongside a rebellious multitude, “Fuera JOH!” (“Out JOH!”), referring to the incumbent president, Juan Orlando Hernández, who many believe fraudulently rigged the elections in his favor to maintain power. The Honduran military and police forces had flooded the streets to enforce the curfew, and the woman was shot in her abdomen, reportedly by a soldier. She was rushed to a nearby clinic where her baby was delivered by emergency cesarean. The child was born with a gunshot wound to the leg.

The curfew and violence were sparked by a strange, contested election. On the day before Hondurans went to the polls, The Economist published evidence of what seemed to be a plan by Hernández’s National Party to commit systematic fraud. The next day, November 26, the election results came in choppy waves: first a sizable lead by Hernández’s opponent, Salvador Nasralla, and then the electronic voting system went off the air. When the system came back up, Hernández was winning. He was then proclaimed victor by a thin margin. International observers noted “strong indications of election fraud,” and a partial recount still handed the win to Hernández. Packed protests and militarized streets followed. As of December 22, human rights organizations in the country have counted more than 30 people killed by security forces, at least four of whom were under the age of 18.

After delivering the wounded baby, the doctor at the clinic sent mother and child to a hospital in Olancho for specialized care. Then, shaken by the experience, the doctor shared with a handful of peers several photographs he had taken of the patients, which he framed carefully to excise their faces. After someone uploaded the photos to Facebook, the doctor received death threats. Although he refused to speak on the record for fear for his safety, the doctor doesn’t know who threatened him. In this province, there’s a sense that danger could come from anywhere.

“I know it sounds conspiratorial,” a journalist from Olancho who followed the baby’s case told me, “but Olancho and the whole eastern fringe of the country are covered in a sort of fog, more than anything due to the drugs that move through the place.” The journalist requested anonymity, like everyone else, because of fear. The journalist’s grandmother worked on a farm in Olancho where 14 people, including religious clergy, were killed in a massacre during land reform protests in 1975. Three more family members died violently between 2012 and 2014, two of them in Olancho. And in the next two years, 19 of the journalist’s family members left the province for the United States, undocumented and desperate.

Similar stories abound. In fact, this reality permeates Honduras, although in Olancho it has a particular flavor. It’s rooted in corruption fed by the Honduran and international elite for generations. Atop this foundation, the 2017 electoral conflict rages – a pyre into which one can be born already a victim of gun violence.

Olancho is the “Wild West” of Honduras, a nickname used even by the U.S. Embassy. It has a slate of mottos to match: “The Sovereign Republic of Olancho,” where it’s “easy to get in, tough to make it out,” and whose swaggering armed cowboys are called “olan-machos.” It has been historically dominated by three gold-rush trades that yielded fortunes for a few: cattle ranching, logging, and mining. Olancho is the birthplace of a legendary bandit, a land of families that evolved into rival clans, where residents are known to claim their nationality first as Olanchano. And in keeping with the autonomous character, Olancho is politically divided: One population center, Juticalpa, is home to the rancher and former president from the right-wing National Party, Porfirio Lobo, so Juticalpa is loyally Nationalist. The other population center, Catacamas, favors Manuel Zelaya, a logger raised there who later became the leftist president ousted in a 2009 coup. The rest of Olancho falls somewhere in between or nowhere at all. Another of the province’s mottos describes the divide: tierra de nadie, no man’s land.

The province of Olancho is larger than the entire neighboring country of El Salvador. It spans much of the eastern end of Honduras. This location has been especially unlucky since 2006, when the pressure of the American drug war rerouted most trafficking off its previous route and instead directly through Central America. Olancho, and the eastern Honduran fringe it dominates, has become a corridor: To the south is the land border with Nicaragua; to the north and east, the Caribbean, which functions as a sea border with producers in South America and consumers in the north. Drugs are forced through whether they float, drive, or fly. “The problem we live is geopolitical — there’s no doubt about that,” said Bertha Oliva, an Olancho native and human rights defender, in an interview in her Tegucigalpa office.

Olancho is gorgeous, with elevated cloud forests flush with orchids and fresh water that tumbles down majestic cliffs, spilling into lowland rainforests or emerald rolling pastures and valleys. But a sinister history lies below the surface and reveals itself only indirectly. As in the white-tipped fence posts that line acres alongside the Olancho highway: a ranch until recently owned by Juan Ramón Matta-Ballesteros, the man contracted by the CIA to run its planes during Iran-Contra, who later engineered the union of the Colombian and Mexican cartels in Central America. Or the unassuming stucco building in a cove off another local highway, marked by a weathered metal sign at the entrance: “El Aguacate Military Runway” — once the landing pad for covert, illegal U.S. supplies en route to the Contras in Nicaragua.

Years later, olanchanos faced new terrors — no longer an imperial counterinsurgency but the drug trade. They remember that time as a free-for-all. Drug planes used the highways as airstrips at midnight. Bulletproof vehicles circulated without license plates, and everyone else had to drive with windows rolled down so they could be easily identifiable as an unthreatening local. There were gun battles at all hours and targeted killings to eliminate people the narcos considered undesirable: gang members, transgender women, street children. And perhaps more than anything, cocaine for individual consumption was available everywhere: around the corner, in the park, at the neighborhood fruit stand. Narcos often paid their Olancho help in-kind.

Interdiction data extracted from the U.S. government’s Consolidated Counterdrug Database show that the amount of cocaine seized in Honduras tripled from 2005 to 2006, hitting 21,320 kilograms. Annual totals remained similarly high until 2009, the year of the coup, when the total skyrocketed again to 70,272 kg. Then, between 2010 and 2011, U.S. federal government agencies reported almost 250,000 kg of cocaine intercepted in Honduras.

Tegucigalpa, aided by Washington, began a crackdown that was visible to olanchanos by 2011. Special forces police, in units known as Cobras and Tigres, accompanied by the military and public prosecutors office, raided mansions, hotels, construction firms, meat-packing plants, mayoral offices, outlet stores, mineral mines, and private zoos throughout Olancho in the next few years. The Cobras police remained to occupy some areas. Residents say they frequently saw U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agents accompanying raids. U.S. agencies registered a drop in intercepted kilograms in 2012 – to just over 68,000 kg – and by 2014, the amount had fallen to about 30,000 kg. In response to the repression, the narcos went underground.

But the narcos who ran wild in Olancho weren’t in charge of the game. The chessboard masters are the elite. In January 2015, the leader of one of Olancho’s own cartels, the Cachiros, was among those caught and extradited to face trial in the Southern District of New York. Once on the stand, Devis Leonel Rivera Maradiaga pointed the DEA to Fabio Lobo, the son of the Olancho cattleman and former president. Fabio was later arrested in Haiti, and his personal cadre of police, who ensured safe passage for the drugs, was arrested in Honduras. Then Hernández’s brother was called to Washington to answer for his apparent involvement with a major trafficker. That same month in a different case, when a Mexican trafficker-turned-DEA informant was asked on the stand who offered to help him move drugs through Honduras, he named Hernández’s current minister of security, Julian Pacheco, a longtime ally of the U.S. military and graduate of the School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia. The informant also said it was Lobo’s son who had introduced him to Pacheco.

Olanchanos aren’t fooled: They know the leaders of the drug game are the same corrupt networks. The streets may be calmer now, but they still rule, and they make their presence known.

Olanchanos recognize the traces of the drug networks because they’re “out of place,” fuera de lugar. For instance: the imported German beers in the dilapidated refrigerators of corner stores across Catacamas, catering to expensive tastes not from around there. The mayor’s office in Concordia, built like a castle, against which lean the homes of residents, clay block shacks. Sightings of limousines that appear suddenly and meander dirt roads. Elegiac poetry books, sold in gas stations around Juticalpa, honoring former Mayor Ramón Sarmiento, arrested for illegal weapons possession.

Another trace of their presence is large enough to be seen from space.

In the summer of 2015, a group of U.S. scientists met in a classroom at the University of Arizona. They have been studying a trend they call narco-deforestation: trees razed because of the drug trade. Suddenly, one scientist gasped and swiveled his computer screen so the rest could see. A Honduran colleague had uploaded to Facebook a satellite image of the middle of a preserved rainforest that traverses Olancho, the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve. The image was a cemetery of hacked trees. The extent of the carnage was almost certainly too big and had happened too fast to be funded by anything other than drugs.

Mark Bonta, a geographer at Penn State Altoona, is one of the scientists and earlier that summer, he was in a truck jostling along a dirt path into the heart of the reserve. Three other people rode with him: Oscar, a teacher and lawyer from Olancho, and José, a farmer-cum-environmentalist in Olancho. I sat beside José. For a while, the lowland rainforest appeared just as a 1.3 million-acre plot of federally protected land ought to: The song of tropical birds buoyed off leafy, wet, dense green. But then we rolled into blight. Recently felled trees smoldered, a gray graveyard extending to the horizon. This is what’s called the “colonization front,” the outer edge of a patch of deforestation.

In the age of the American drug war, Olancho’s traditional trades — logging, cattle-ranching, mining — double as vehicles for laundering money and moving drugs. They all lead to deforestation. The logging-to-cattle cycle is particularly useful: Use drug profits to chop trees, grow grass, buy cows, and every step of the process is like a magic wand that transforms bad money into good — and yields a return on the investment. When it’s time to physically move drugs out of the region, send a semi-truck full of those products across the border. Cocaine has been found in many exported Honduran products, including logs, cattle, tomato paste, and coconuts.

That day, as we drove on, we passed pastures of long-ago deforested land, now grassy hills flecked with shining cattle. The scene wouldn’t look out of place in Kentucky, but this is a rainforest preserve.

We took a pitstop when the dirt path hit a patch of houses. A man there told us he worked providing transport, driving his truck up and down the road. He said that the “secreto a voces,” the spoken secret, is that the cattle farms around here are mostly owned by narcos. He said that just across the Coco River that divides Honduras from Nicaragua, the farthest point his work takes him, there are large ranches owned by Colombian traffickers. We heard similar rumors that day about multiple other regions of the country: Narco operations, sometimes in collaboration with international outfits and sometimes under homegrown capos, are to blame for the broken trees.

In fact, satellite images produced by the scientists show active deforestation of lowland rainforest in five Honduran national parks, including the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, a growing colonization front that spans the country like a horizontal belt. Not all this deforestation is narco-related. After all, logging and ranching are historic trades in the region. The drug connection is a scientific hypothesis based on satellite images of unusually rapid land-use change, located in well-known trafficking routes, triangulated with the testimonies of people on the ground and reports from organizations that follow the tides of corruption.

We piled back into the truck, and along the way we offer rides to various local residents we found walking along the edge of the road. One passenger told us his nephew, a mechanic, took a job with a company in the Río Sico area of the Biosphere Reserve, in La Mosquitia territory. (La Mosquitia is northeast of Olancho, the site of an infamous DEA-involved massacre.) The man said his nephew arrived to discover his new employer was a mineral mine owned by Colombian narcos. The nephew is only occasionally allowed to return home to bring his earnings to his family, the passenger said.

He is one of many people unwittingly recruited into the service of traffickers, said Migdonia Ayestas, the coordinator of a project that collects and analyzes data on violence, based at the National Autonomous University of Honduras or UNAH. It’s common to be hired for illicit duties masked as a normal profession, said Ayestas, and hard to extricate yourself from the situation: As soon as you know it’s a narco operation, you know too much. Leaving the job means going rogue. Drug money so thoroughly permeates everything that when Ayestas’s project was awarded a grant from the government of Spain to investigate campaign finances in 2014, the university had to give the money back, she said in an interview in her campus office. “We couldn’t find anyone willing to take the job. People say all the time, ‘Where did that political campaign come up with so much money?’ We wanted a scientific answer to that question,” she said. “We couldn’t because no one dared do it.”

Edmundo Orellana, who has served as the Honduran public prosecutor, the minister of defense, and delegate to the United Nations, has said that the Honduran economy runs on money laundering. In a phone interview, he said he began to notice legitimate industry used to launder illicit funds in the 1990s when he was public prosecutor. Moguls and politicians were “animated by how easy it was to make money, but also by the security that the justice system wasn’t going to catch up with them.” And then came the drug war. “Honduras’s current situation, in which it has been a victim of drug trafficking and organized crime in general, is the fault of the United States,” he said, continuing that it is U.S. strategy that pushed the drug war into Central America. “What the U.S. is doing from its perspective is good, it’s right. But from Hondurans’ perspective, the problem has become ours.”

Orellana also points to high-level local control of the drug trade. To illustrate, he uses the case of the Cachiros cartel. “When someone at the U.S. Department of Justice called someone in the Honduran government [in 2015] to request the capture and extradition of the Cachiros,” Orellana said, the U.S. mentioned a particular concern: The cartel owned a construction company that was among the Honduran government’s favored contractors for paving highways.

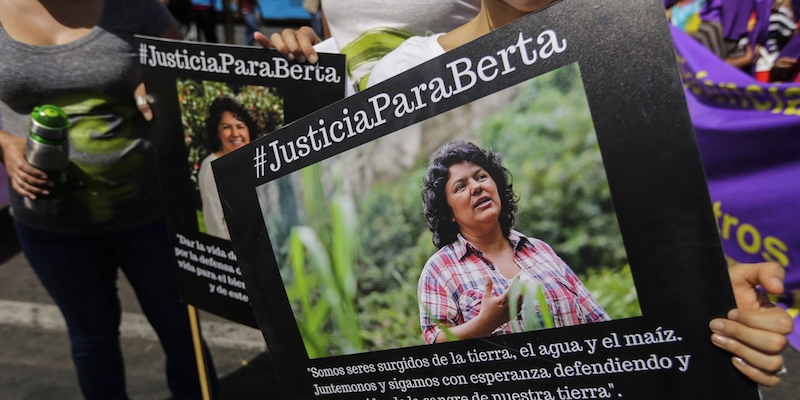

Hernández, who has held office since 2014, is uncomfortably close to drug trafficking — in terms of the sheer volume that has occurred on his watch and because of the alleged narcos among his own people. Other criticisms include his attempts to bring all branches of the government under his control, from the Supreme Court to the public prosecutor, to the Supreme Electoral Tribunal and the military police force. Then there’s the fact that Honduras has become, under him, the deadliest place in the world for environmentalists. That reality is especially evident in the unsolved murder of Berta Cáceres, but is widespread beyond her case.

When environmentalists protect natural resources, they threaten the profit of those who’ve monopolized land and water — some of whom are not only politically powerful but are also documented traffickers. An example is the late Miguel Facussé, who was among the wealthiest businesspeople in Central America. His company Dinant was backed in the past by the U.N. and now by the World Bank. Facussé was suspected of drug trafficking by the U.S. government, and Dinant is still the owner of thousands of acres of palm oil plantations on disputed land. While defending that land, more than 100 farm workers have been killed by Facussé’s private security forces working in concert with the Honduran military, which illustrates another piece of the puzzle. When environmentalists resist such characters, they often face retaliation from state security forces acting at the landowners’ behest, as happened with Cáceres. The Honduran police and military have been trained by the U.S., Israel, and Colombia, funded by millions of U.S. dollars annually.

The U.S. government has always known about the inbred kleptocracy of Honduras. One of the more quirky examples of such knowledge was a State Department cable written in Tegucigalpa about U.S. fast food franchises in Honduras. The cable’s author remarked that the same handful of families owns the rights to brands like McDonalds, Burger King, Pizza Hut, and Pepsi, and benefits from “dubious” tax breaks awarded them by a friendly Congress with seemingly no legal explanation, except the flimsy argument that gringo chains bring tourism. (Has a gringo ever traveled to Tegucigalpa to eat a Big Mac?) Another cable, written after Mel Zelaya was elected president, noted that Zelaya’s father-in-law is a prominent lawyer who, at the time, counted among his clients some people who are nominally Zelaya’s political enemies, prominent National Party members. One of the clients was Facussé, the palm baron. The cable also noted that Zelaya’s father owned the Olancho farm that was the site of the 1975 massacre of land reform advocates.

Yet successive U.S. administrations have chosen to cultivate that oligarchy, especially the faction from the political right. Enter President Juan Orlando Hernández, described in a State Department cable as someone who has “consistently supported U.S. interests.” Hernández earned a master’s degree in public administration at the State University of New York at Albany and has a brother who had received extensive care at U.S. army hospitals after being injured in a military parachuting accident.

Now Hernández and his National Party are roundly and globally scrutinized for mounting evidence of electoral fraud. Yet two days after the election, the U.S. State Department certified Honduras as a country that fights corruption and respects human rights and thus, can receive millions of dollars in U.S. aid. On December 2, the U.S. Embassy in Tegucigalpa announced it was “pleased” with the ballot recount, saying it “maximizes citizen participation and transparency.” Three days later, U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy led a small chorus of congressional rebuttal: “Those of us who care about Central America have watched the election for Honduras’ next president with increasing alarm,” he wrote, citing “a process so lacking in transparency” with “too much suspicion of fraud.” Of the U.S. Embassy’s “troubling” role in the crisis, the senator wrote, “I hope it is not a new standard.”

In fact, it appears to be an old standard, if not a tradition.

On December 17, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal officially crowned Hernández president-elect. That night, the delegation of election observers from the Organization of American States recommended the results be scrapped and that a new election be held. Despite increasing calls from U.S. senators to support the OAS verdict, on December 20 a senior State Department official said that unless presented with additional evidence of fraud, the U.S. government has “not seen anything that alters the final result.” Two days later, the State Department sealed Honduras’ fate, congratulating President Hernández on his victory, prescribing a “robust national dialogue” to “heal the political divide,” and advising those who claim fraud to recur to Honduran law. The Department ended its statement by calling upon Hondurans to refrain from violence.

Top photo: Residents get away from clashes between riot police and supporters of opposition candidate Salvador Nasralla, during protests in Tegucigalpa, on December 18, 2017.

Posted at https://theintercept.com/2017/12/23/honduras-election-fraud-drugs-jose-orlando-hernandez/