There were Egyptian elections before Mohammed Morsi, who underestimated the anti-democratic impulses of Arab tyrannies, and assumed Western governments wouldn’t stand for an overthrow of a democratically-elected president.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

July 3, 2019

The death of Mohamed Morsi, former Egyptian President, in an Egyptian court two weeks ago focused attention—albeit briefly—on the nature of the tyrannical regime of Gen. Abdul-Fattah el-Sisi. El-Sisi’s coup in 2013 was largely the work of the UAE-Saudi alliance and was quickly blessed by the Obama administration.

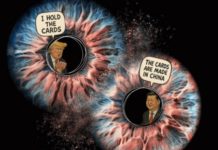

el-Sisi has done everything possible to endear himself to the U.S.: he has brought his security coordination with Israel to an unprecedented level and has even allowed Israeli fighter jets to conduct raids on Egyptian territory (in the Sinai). He also has tightened the grip of his regime on Gaza, reinforcing the Israeli siege. Those are the priorities of the U.S. in Egypt, along with political subservience to U.S. dictates.

The Muslim Brotherhood is now the object of state and regional harassment in most countries under Saudi and UAE influence. Western governments, which for decades supported or indulged the Brotherhood in the long years of the Cold War, have come under pressure from the Saudi and UAE regimes to outlaw their organizations and declare them terrorist groups. Qatar and Turkey, who are now the official sponsors of the Brotherhood, lobby Western governments to keep the Brotherhood off the terrorism list.

But there is a paradox in the UAE-Saudi-Israeli campaign against the Brotherhood: the few cases where there were elections in the era of Arab uprisings (in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Yemen), the Brotherhood proved that they are a powerful political force who command support from a substantial segment of the population. Banning the Brotherhood in the Gulf merely pushes them underground.

The bitter campaign against the Brotherhood in the UAE and Saudi Arabia is a testimony to their political salience, not to their irrelevance; both regimes are concerned that the domestic opposition prefers the Brotherhood to the ruling dynasties. A recent Arab public opinion survey (with very questionable methodology and phraseology conducted by the Arab Barometer, which is partly funded by the U.S. government) reveals a wide popularity for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdo?an among the Arab population. (One notices in talking to Saudi students abroad that Turkey constitutes the most attractive model for young educated Saudis because its version of Islam is more palatable than the House of Saud’s).

Morsi’s Miracle Run

Morsi became president of Egypt in 2012, and lasted almost a year. It was a miracle that he lasted that long given the Gulf regimes’ insistence on imposing tight control over the Arab state system. The West, especially the U.S., learned to live with the Brotherhood, particularly its branches in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, who all proved willing to abandon past slogans in relation to Israel. Their economic policies were also congruent with Western lending agencies. But Morsi underestimated the anti-democratic impulses of Arab tyrannies, and he also assumed that Western governments would not stand for an overthrow of a democratically-elected president.

The era of Morsi in Egypt was an interesting one; it is said that he was the first democratically elected president of Egypt. But who can question that Gamal Abdul-Nasser (who ruled from 1952-1970), was the most popular Arab leader since Saladin, captuing the hearts and minds of Egyptians from at least 1956 until his death? Egyptians continued to be loyal to Nasser even after the 1967 defeat to Israel, and his funeral remains the most massive Arab funeral in history (and one of the biggest ever worldwide). There were elections in Egypt under Nasser and wide sections of the social classes were represented in ways that parliaments under capitalism aren’t. (Naser broke the monopoly of the upper classes over political representation).

Elections in Nasser’s time were not held in the context of a multiplicity of political parties, but that does not cast doubt on the legitimacy of the successive elections of Nasser as president. Even if the Brotherhood were allowed to field their own candidates during the 1950s and 1960s, they did not stand a chance in that secular era.

The election of Morsi took place in a different context. There was a multiplicity of political parties but the elections were not entirely free (assuming that you can have free elections per se, especially in developing countries where foreign money and foreign embassies play a big role in influencing and determining results). The state apparatus clearly intervened to support the candidacy of Ahmad Shafiq against Morsi, and Gulf and Western governments most likely funneled money to the campaign of Shafiq, just as Qatar and Turkey intervened on the side of Morsi, who probably won with a larger margin than the one announced by the state.

The year of Morsi was an interesting period in contemporary Egyptian history. It was by far the freest political era, where political parties and media flourished and the state tolerated more criticisms against the ruler than before or since. But young Egyptians who participated in the 2011 revolt stress the point that freedoms under Morsi were not so much a gift from the leader to the people as they were the result of insistence on their rights by the revolutionary masses. They had just managed to oust the 30-year rule of Hosni Mubarak and they were not going to settle for less than an open political environment.

But that also did not last, and the rise of el-Sisi was entirely an affair hatched by foreign governments and the security apparatus of the state. Secular, liberal, Nasserists, and even some progressives were accomplices of the coup of 2013; they were alarmed with the Islamic rhetoric of the Brotherhood and some even resented the political rise of poorer Egyptians with an Islamist bend. el-Sisi knew how to appeal to a large coalition and to pretend that he would carry on the democratization of Egypt. But the signs were on the wall: the blatant role of the Saudi and UAE regime in his coup were not disguised, and el-Sisi was an integral part of the Egyptian state military-intelligence apparatus, whose purpose is to maintain close relations with the Israeli occupation state, and to crush domestic dissent and opposition.

Morsi’s fate was sealed when he decided to coexist with the same military council that had existed in the age of Mubarak. He could have purged the entire top brass, and replaced them with new people who were not tainted with links to the Mubarak regime. Worse, Morsi made the chief of Egyptian military intelligence—the man who is in charge of close Israeli-Egyptian security cooperation—his minister of defense (that was el-Sisi himself). Morsi assumed that the military command would quickly switch their loyalty to the democratic order instead of the old tyrannical regime.

Not Dead Yet

It is too premature to write the obituary of the Muslim Brotherhood. It is still a force to be reckoned with in many Arab countries, and whenever the people are given a chance to express themselves in the ballot boxes, the Brotherhood will be represented. But it is tainted: in the experience of Tunisia and the brief experience of Egypt under Morsi, the Brotherhood proved to be quite unprincipled, in both foreign and domestic policies. It has also engaged in armed combat in Libya, Syria, and Yemen.

Morsi was mocked and condemned mercilessly for a formal congratulatory letter that the then Egyptian president wrote to then Israeli President Shimon Peres. The Brotherhood’s old rhetoric about “Jihad against Israel” was quickly discarded to win approval from the U.S. The Brotherhood had semi-formal deals with the Israel lobby in Washington and with the late Sen. John McCain to prove its good intentions if allowed to reach power.

The death of Morsi did not so much create sympathy for his person as much as it underlined the cruel repression under el-Sisi. Political satire flourished under Morsi and Bassem Yousef owed his career to him (Morsi was quite easy to mock). The Brotherhood in Egypt are not finished; they will come back, and their return will unlikely be peaceful.

* As’ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the “Historical Dictionary of Lebanon” (1998), “Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), and “The Battle for Saudi Arabia” (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil