By Omer Ozkizilcik

18 May 2022

If safety is assured and sufficient infrastructure is built, more Syrians would be willing to return

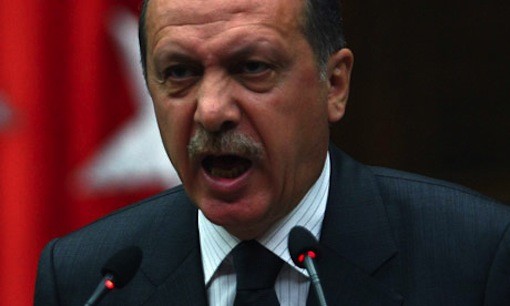

The Turkish government’s plan to return one million refugees to northern Syria comes as public resentment against Syrians has reached a boiling point, amid opposition propaganda and economic hardships spurred by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Elections are on the horizon next year, and the opposition will likely play two prominent cards against the government: the economy and the migration crisis. To ease this pressure and avoid an increase in crimes against the refugee population, the government wants the public to know that an alternative is possible.

In Turkey, Syrians are not assessed for refugee status; rather, they fall under temporary protection. Under this regime, the government must find ways to facilitate their voluntary return to Syria. If those willing to return do so, it would take some of the pressure off those who choose to remain in Turkey, allowing them to integrate better into Turkish society.

How this could be achieved remains a matter of some debate. The Turkish opposition has argued that if elected, they could normalise relations with the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and strike a deal to enable the return of refugees.

But this option has been tested by other countries, without much success. Jordan and Lebanon have normalised relations with the Assad regime, but most Syrians have not gone back. According to UN data, since 2019, more than 37,000 Syrian refugees have voluntarily returned from Lebanon and more than 40,000 from Jordan, while hundreds of thousands more remain in those countries.

In Turkey, which hosts the highest number of Syrian refugees at more than 3.5 million, around 81,000 returns were verified in that timeframe, although some cases might not have been recorded by the UN.

Safe zone

According to the Turkish interior ministry, the numbers are significantly higher. Since Turkey’s establishment of a northern safe zone in Syria, around 500,000 refugees have voluntarily returned, the ministry said in March. But after displaced Syrians inside the country also flocked to these Turkish-protected areas, around five million people are now crowded into a small region without the necessary infrastructure.

As underlined by the UN, the return of refugees must be voluntary, dignified and safe. While Turkey is responsible for ensuring safety in the areas it protects, Idlib has been repeatedly hit by Russian air strikes and suffers from political instability. Turkey’s deployment of its newly produced Hisar-O air defence systems could improve the security situation in Idlib, and the Russia-Ukraine war has also bought Ankara additional time.

To ensure a dignified return for Syrians, there must be assurances that refugees will not subsequently be persecuted. To this end, improving the overall internal security situation and resolving issues of factionalism within the rebel Syrian National Army and the opposition Syrian Interim Government would help to ensure prospective returnees that the process can be trusted.

In Idlib, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) poses a threat to the aspirations of the Syrian people, but it is limited by the presence of Syrian and Turkish forces, as well as by it own agenda to come across as a reasonable actor. HTS wants to be removed from international terrorist lists, but for Turkey, its progress may not be fast enough – and Russia may exploit the presence of HTS to continue its attacks. Without a solution to the presence of HTS, a sustainable return of Syrians will be difficult.

Vital aid

If safety and dignity are assured, and sufficient infrastructure is built to house Syrians, more and more would be willing to return to the country, even if they could not immediately return to their hometowns. The area between Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ayn offers significant room for housing and infrastructure projects, and Turkey has the capacity to build there on its own.

Investment projects in Turkish-protected areas in northwestern Syria would likely come with a higher price tag, as hundreds of thousands of internally displaced families would also seek to benefit from any new developments. In addition to housing and infrastructure, there is also a critical need for healthcare and education.

But at a time when Britain is cutting back on financial aid to Syria, leaving thousands of children without access to education, it seems unlikely that European states would contribute to the Turkish project. While more funds may be forthcoming from Qatar and Kuwait, this may not be enough. In addition, Russia is expected this summer to veto the UN cross-border aid mechanism for Idlib, blocking the inflow of vital humanitarian assistance.

If sufficient funds cannot be allocated to ensure the safe and dignified return of Syrian refugees, the Turkish government will almost certainly not reach its one-million target.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.