By Franklin Frederick

On 25 September 2020, the Swiss Parliament passed a revision of the federal anti-terrorism law. This new law provoked many protests, some quite vehement, including the launch of a national referendum. One of the main instruments of direct democracy as practised in Switzerland, the people’s referendum allows the citizenry to vote to approve or nullify laws voted by Parliament. To organize such a vote, 50,000 valid signatures are required (from an overall population of 8.6 million) accompanied by each signatory’s legal address, subsequently certified by the relevant authorities. Owing to the pandemic, the collection of signatures has been done mainly on-line, and the result seems to have already exceeded double the required number.

This popular reaction to the new legislation is very welcome because, according to the website of those who launched the referendum (https://detentions-arbitraires-non.ch/), the new law would abolish the presumption of innocence: “The measures provided for in the law are not to be ordered by a court, but by the police on the basis of mere suspicion (no evidence needed). This violates the European Convention on Human Rights” to which Switzerland is a party.

The website points out further violations of the European Convention: “One can be placed under house arrest for up to nine months without evidence, on mere suspicion. This would make us the first and only Western country to have such arbitrary deprivation of liberty. The only exception: the USA with its camps in Guantanamo.”

Even more disturbing, the new law violates the Convention on the Rights of the Child, for its measures allow the imposition of compulsory registration and a ban on minors 12 years and up leaving the country, as well as house arrest from the age of 15. The protection of minors is thus seriously undermined.

Fifty law professors from Switzerland have communicated their concerns to the federal government (the Federal Council): https://www.amnesty.ch/de/laender/europa-zentralasien/schweiz/dok/2020/antiterror-gesetz-aushoehlung-des-rechtsstaates/pmt-offener-brief.pdf .

And experts from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights itself warned that this new legislation violates international human rights standards in the way that it expands the definition of terrorism, and would set a dangerous precedent for the suppression of political dissent worldwide.

The experts were particularly alarmed that the bill’s new definition of ‘terrorist activity’ no longer requires the prospect of any crime at all. On the contrary, it may encompass even lawful acts aimed at influencing or modifying the constitutional order, such as legitimate activities of journalists, civil society and political activists.

The experts also warned against sections of the bill that would give the federal police extensive authority to designate “potential terrorists” and to decide on preventive measures against them without meaningful judicial oversight.

Under the guise of the ‘fight against terrorism’, many governments seek to suppress any legitimate criticism of the neoliberal economic model. Thus, laws supposedly created to ‘defend democracy’ are actually instruments in defence of a particular economic order: neoliberalism. What is new in this Swiss legislation is the possibility of criminalisation of young people from the age of 12 (!), as mentioned above.

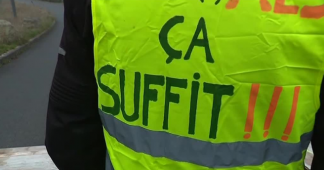

The obvious target of such criminalisation is the climate movement. An increasing number of young people have taken to the streets in various parts of the world with clear and forceful criticism of the lack of effective action by governments in relation to the seriousness of global warming, drawing attention above all to the contradiction between neoliberal capitalism and environmental preservation. This movement has grown exponentially in Switzerland, becoming a political force to be reckoned with.

In September 2018, for example, the largest demonstration ever recorded in the history of the city of Bern occurred: some 100,000 people, mostly young, took to the streets in protest. This movement had a decisive effect on the parliamentary elections that followed in October, leading the Green Party to obtain the largest vote in its history.

On 21 September 2020, the young activists occupied Bern’s Federal Square, in front of the Parliament building. This action produced a considerable stir the international media, and messages of support to the activists came from various parts of the world, including from the Landless Movement (MST) and several parliamentarians from Brazil.

The occupation, which was totally peaceful, was shut down by the police and triggered reactions that were not without overtones of outright hysteria from many members of parliament and a major part of the Swiss media, all of whom condemned the activists’ ‘illegal’ action. Some parliamentarians even asked the intelligence service to investigate the young people. More recently, another Swiss parliamentarian compared the occupation to the invasion of the U.S. Capitol by far-right demonstrators!

Under the new law, most of the young people involved in the occupation could be accused of ‘terrorism’ – and punished accordingly. Thus, fighting for the future of the planet has become a ‘crime’ to be punished by the state!

But how was it possible that legislation allowing the criminalisation of children from the age of 12 as ‘terrorists’ was proposed and approved by the parliament of a country as democratic and enlightened as Switzerland?

Such legislation has long been the dream of the extreme right in Brazil, which has fought fiercely for the possibility of criminalising both social movements and young people. Bolsonaro and his supporters would love to enact similar legislation in Brazil and will probably try to follow this Swiss example.

The political forces in Switzerland behind this law have a long history, which is also partly the history of the construction of the neo-liberal order itself. In an important book, The Road from Mont Pélerin, a collection of essays by several authors on the history of neo-liberalism, Dieter Plehwe wrote in the ‘Introduction’:

The transnational dimension of the local/national history of neoliberalism has been particularly strong in the U.K. and the United States. Switzerland also deserves recognition as a particular transnational neoliberal space because of the hospitality of Swiss neoliberal intellectuals and institutions to Austrian, German, and Italian refugee neoliberals. It was certainly not mere coincidence that the Mont Pélerin Society was founded in this country: only Switzerland provided neoliberal intellectuals the intellectual and institutional space and financial backing needed to organize an international conference of and for neoliberals right after World War II. Until the end of the 1950s, it remained easier for neoliberals to congregate in Switzerland than anywhere else: four of the ten Mont Pélerin Society meetings between 1947 and 1960 took place in Switzerland. It took more than ten years after the war for a meeting to be held in the United States.

Those political and economic forces that made Switzerland so receptive to neoliberal ideology by providing neoliberals the intellectual and institutional space and the financial backing, ahead of any other country, are still very active and are the driving proponents of the new law.

In another essay in The Road from Mont Pélerin Keith Tribe wrote:

What distinguishes neoliberalism from classic liberalism is the inversion of the relationship between politics and economics. Arguments for liberty become economic rather than political, identifying the impersonality of market forces as the chief means for securing popular welfare and personal liberty.

Thus, any criticism of neoliberalism becomes criticism of freedom itself, and should be punished by the State as ‘terrorism’.

And in the same book, Rob van Horn and Philip Mirovsky observed that ‘neoliberalism is first and foremost a theory of how to engineer the state in order to guarantee the success of the market and its most important participants, modern corporations.’

Many of these large corporations have been the target of the climate movement’s most incisive criticism, causing much damage to their corporate public image. It is not surprising, then, that the market’s ‘most important participants’ are behind the drafting of specific legislation to control these ‘abuses’.

That such an anti-terror law has been passed by the Swiss parliament reveals the power of neoliberal ideology within this country and the ability of large corporations to influence governments and legislation even in a recognized democracy such as Switzerland. At a time when neoliberalism is failing all over the world, a reaction from the neoliberal establishment is to be expected, for neoliberalism can be sustained only by lying, by force or by a combination of the two. But the neo-liberal lie can no longer hoodwink the world’s peoples, for the failure is too visible, too eloquent. Neoliberalism, for its own survival, is left with the use of violence and repression, by all possible means, including legal ones.

Switzerland’s humanitarian and democratic tradition is now in the hands of its young activists. The climate movement has the potential to transcend borders and generations, to unite the North and South of the planet in a common struggle for our mother Earth against those who exploit it. But the combined reaction of economic and state power can be overwhelming, and laws like these clearly show the risks and dangers to which these young people are exposed. It is up to each of us now to support this struggle with the creativity, affection and joy that the preservation of life deserves.