By Tamara Kunanayakam

former Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations in Geneva

April 3, 2018

The question repeatedly asked of me, a major preoccupation of all patriotic Sri Lankans, is how implementation of the Human Rights Council (HRC) Resolution 30/1 will affect Sri Lanka’s future and whether it will affect the country’s sovereignty.

Let’s be clear, its implementation is not for tomorrow, it is already happening and the consequences are there for all to see, and experience.

The demands articulated in the US-led resolution are being fast incorporated into the law of the land through a series of radical reforms and the drafting of a new Constitution. Ever since Yahapalana was installed in power in January 2015, we have seen a flurry of activity in making, breaking, reforming and amending institutions of State and laws of the land.

Some reforms are known, others are being drafted and negotiated behind closed doors. Many are being hurriedly rushed through without consultation with the people or debate in Parliament, particularly when these violate the country’s Republican Constitution. The recent anti-Muslim riots provided an ideal opportunity for Yahapalana to rush through the controversial Enforced Disappearances Bill, which obliges Sri Lanka to extradite its own citizens to be tried in foreign courts.

. It is a fact that external actors, including Washington, the United Nations, and the Washington-based financial institutions, the World Bank and the IMF, are not only better informed, but are active partners in the process, including through funding and drafting.

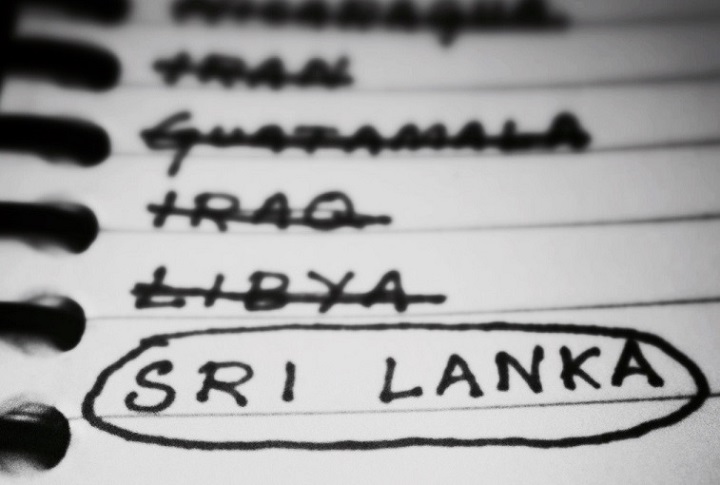

US interference in reform process is both direct and indirect: (a) the resolution itself was drafted in and by Washington; (b) the enforcer is Jeffrey Feltman, formerly with the US State Department, now masquerading as UN Under Secretary General for Political Affairs, who is an arch neoconservative notorious for engineering regime change in countries of strategic interest to Washington, destabilization, the break-up of sovereign States into ethnic enclaves, and fomenting violence; and, (c) the role of monitor and prosecutor is that of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, once a multilateral institution, now hi-jacked by Washington.

Once the hidden agenda behind HRC resolution 30/1 is understood, how it impacts on our sovereignty will be clear. We must remember that it was not formulated by the Sri Lankan people, but by a foreign power, the USA, whose sole interest is to turn our country into an aircraft carrier to contain and roll back China as part of its imperial ambition of maintaining global hegemony.

Responsibility to Protect or R to P, the right to intervene

Underlying the resolution is the controversial norm Responsibility to Protect or R to P, advanced by Washington. Its objective is to condition State sovereignty and legitimise unilateral US intervention in the internal affairs of sovereign States if and when necessary to achieve its goals. Accountability is the pillar on which R to P stands. Washington and its Western allies claim that an amorphous “international community,” by which they mean themselves, has the right and responsibility to intervene unilaterally, preemptively and preventively, including militarily, in countries where they believe Governments are unwilling or unable to protect their citizens from genocide, ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

The unequal power relationship between States ensures that, in practical terms, R to P is a weapon in the hands of the powerful to be utilised against weaker States that opt for an independent path. R to P is the modern version of the “White Man’s Burden” of the late 19th century used by the US and Great Britain as justification for their savage colonial wars. It is a project of re-colonisation, associated with bringing countries under their tutelage.

“Transitional justice,” from free people to tutelage

Resolution 30/1 does just that. It seeks to bring Sri Lanka, a country of strategic importance to Washington, under its control. The term “transitional justice” in the resolution refers to the range of measures to transform Sri Lanka from independent Republic to a people under tutelage, consolidating at the same time the regime change engineered by Washington on 8 January 2015.

Good Governance, or Yahapalana in the Sinhala, is the means whereby that consolidation takes place, the term coined by the US Treasury, IMF and the World Bank for political conditionality imposed on indebted Third World countries such as ours to make us permanently indebted and dependent, facilitating external interference and domination. Invented in the late 1980s with a collapsing Soviet bloc and the emergence of a unipolar world, ‘Good Governance’ became part of Washington’s arsenal of soft-power weapons to consolidate its global hegemony.

Similarly, the term ‘transitional justice’ was broadened in the late 80s and early 1990s from measures relating only to jurisprudence to cover institutional reform, reform of the political system and devolution of political authority; reform of the judiciary and law enforcement; security sector reform, including military; vetting of public officials as was done in NATO-occupied Afghanistan, where election candidates were vetted in the 2009 and 2010 elections; fiscal reform; the liberalization of finance and trade; privatization and sale of public assets to foreigners, including the country’s natural wealth and resources, etc., etc.

The resolution ensures external control over State institutions and domestic mechanisms through the direct involvement of foreign actors in these entities. As elsewhere, domestic opposition is temporarily overcome by the establishment of parallel institutions and through “privatisation” or “outsourcing” of important State functions. In a revealing report (Rule of law tools for post-conflict States, 2006), OHCHR considers that such reforms are for the good of the people and must, therefore, be imposed even against their will. To overcome domestic opposition, an international mandate will be obtained “to provide international actors with the authority and means to intervene directly in domestic affairs and overrule domestic procedures if necessary.”

Universal jurisdiction, extradition as a permanent threat

“Universal jurisdiction” is another highly controversial concept accepted by Sri Lanka, but formally rejected by the African region as a Western tool for recolonialisation. It can be found in HRC resolution 30/1, in the reports and statements on Sri Lanka by the High Commissioner for Human Rights and in the interventions of Washington and its Western allies. At the recent Human Rights Council sessions, the High Commissioner threatened those opposed to international intervention inside Sri Lanka by calling on States to explore application of universal jurisdiction against Sri Lanka.

Worse than any external imposition of tutelage, is its acceptance by the Yahapalana regime and its ratification by forcing through the Enforced Disappearances Bill in Parliament while public attention was diverted to the recent anti-Muslim violence.

Universal jurisdiction is based on the Princeton Principles on Universal Jurisdiction, developed at the initiative of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), an organization initially partially funded by the CIA through a front organization, the American Fund for Free Jurists. Today, the US State Department, the European Commission, and several European Governments, among others, fund the ICJ.

Universal jurisdiction allows a State to try a person for alleged mass atrocities even if it did not happen within its own territory and the perpetrator or victim are not citizens of that State. The justification is they have become international crimes, beyond nationality, through the adoption of international conventions on torture, enforced disappearances, genocide, among others, and that individual States can act on behalf of the international community to bring perpetrators to justice.

Universal jurisdiction goes even beyond the International Criminal Court (ICC). Whereas the ICC jurisdiction is limited unless expanded by the Security Council, universal jurisdiction can be applicable to crimes committed anywhere, and tried anywhere, at any time. Moreover, extradition requests can remain valid for decades, and the person cannot ever be certain of being free of prosecution even if he or she has been granted safe haven in another country.

The Yahapalana betrayal

By co-sponsoring the resolution and deviously implementing the demands therein, the Yahapalana regime has not only committed the country to wide-ranging reforms, many of them unconstitutional, without a mandate from the people or Parliament, but opened wide the door to its recolonisation.

By permitting external intervention in the internal affairs of the country, it has given credence to Washington’s claim that our institutions are incapable and incompetent, and that we are incapable of governing; it has permitted the usurpation by foreign powers of the sovereign right of our peoples to determine the type of society they choose to live in; and, it has undermined our economic sovereignty, depriving the people of the autonomy necessary to exercise their political sovereignty, and the means necessary for a life with dignity for the majority of Sri Lanka’s population who depend on the real economy for their livelihood.

The accountability referred to in the resolution is not about accountability toward the citizens of the country, but accountability toward the self-appointed global policeman, the US. That is why, the installation of Yahapalana has brought with it the new habit of the political leadership, whether President, Prime Minister or Cabinet, reporting not to people or Parliament, but to Washington, direct or indirectly through the United Nations.

The leadership has not only abdicated its responsibility once by signing resolution 30/1 in September 2015; it persisted and signed again in March 2017 (resolution 34/1), and, then, only 4 months ago, in November 2017, reiterated a “very firm” commitment to fully implement the resolution. The commitment was made by the Head of Delegation to the HRC’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in Geneva, Harsha de Silva, Deputy Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs. And, as though the nail needed further hammering into the coffin, the Foreign Secretary Prasad Karyawasam felt it incumbent upon him to play back the commitment at the same meeting.

Without the second resolution 34/1, there would have been no report on Sri Lanka by the High Commissioner at the recent session of the Human Rights Council, and no threat of ‘universal jurisdiction’ against Sri Lanka.

Can Sri Lankan sovereignty be restored?

Many wander how the process taking Sri Lanka down the path to Puppetdom can be reversed in Geneva.

Under the UN Charter, resolutions adopted by the General Assembly, including subsidiary bodies such as the Human Rights Council, are recommendations only and not legally binding on Member States. Numerous resolutions are never ever implemented. The US, for instance, has never implemented the annual resolutions calling for lifting of its criminal blockade against Cuba, nor has Israel the hundreds of resolutions on Occupied Palestine. The simple solution, therefore, is a technical one: ignore the resolution and mobilise the support of Sri Lanka’s natural allies to take Sri Lanka off the Council’s agenda. Concretely, this would mean ensuring there is no resolution against Sri Lanka or one that does not have an operative paragraph requiring the Council to consider the matter at a future session.

Our problem is not, however, a technical problem; it is a political one and will require a political solution.

It is not Washington, but our own Yahapalana Government that brought this disaster upon the Sri Lankan people. The resolution is binding only because Yahapalana wants it to be binding. Two resolutions abdicating sovereignty, eternal pledges to our detractors to implement, and a plethora of reforms over a three year period would not have been possible without a minimum of complicity between the coalition partners.

It is here then, on our own territory, that the problem lies; it is here, on our own territory, that implementation takes place; and, it is here, on our own territory, that we can and must resist!