By Lasanda Kurukulasuriya

The Indian Ocean has been the focus of frequent and intense diplomatic activity in the past few years. These interactions have had a regional character, while the involvement of external players in the discussionshas also been notable. These developments,while they highlight the centrality of the Indian Ocean to big power competition in an evolving multi-polar world, at the same timedemand critical appraisal. Smaller players like Sri Lanka especially need to be mindful of who’s setting the agenda at these deliberations, and alert to the ever-shifting power equations between and among the big players.

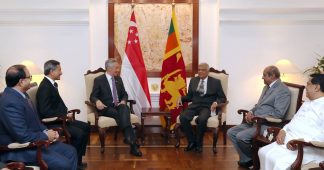

With its pivotal geographical location in the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka has naturally been an active participant in these forums. Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has addressed three Indian Ocean Conferences (IOCs)– in Singapore (2016), Sri Lanka (2017) and Vietnam (2108)and this month participated in a panel discussion of the World Economic Forum on ASEAN, again in Vietnam, where he spoke on ‘Asia’s geopolitical outlook.’

The Prime Minister in his speeches at the three IOCs has,to his credit, adopted a somewhat independent stance rather than uncritically ‘toeing the line’ of any big power. Although he supports‘freedom of navigation and overflight’–which is the rallying call of the US, endorsed by its allies in the face of ever-growing Chinese maritime influence – Wickremesinghe has consistently made a case for the littoral states to play a more assertive role in setting the rules. “The littorals, by geographic design, are integral partners in this process” he saidat the conference on ‘Building regional architectures’ in Ha Noi last month.

Another consistent thread in his presentations has been his questioning of the concept of ‘Indo-Pacific,’ a US creation.He assertsthat the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean are distinct entities. India too has been careful in its use of terminologyin this respect.

At the inaugural IOC in Singapore (2016) Wickremesinghecalled for “an inclusive, multilateral strategic security order” warning that there will be “resistance to any country unilaterally trying to shape the strategic order of the region.” He further said “This order should be built on a consensual agreement and no singular state should dominate the system.”

The question for analysts would be how the PM proposes to reconcile the laudable goal of a democratic, consensus-based order, with the hegemonic stance adopted by the world’s superpower. US foreign policy particularly under the Trump administration is rooted in the idea of US‘exceptionalism’ –which it uses to bully the rest of the world into compliance with its wishes,using the threat of sanctions. This belligerent approach is most apparent in itspolicies towards Russia and China. In a statement last month to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the subject of ‘US strategy towards the Russian Federation,’ Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs Wess Mitchell is reported as saying:

“Russia and China are serious competitors that are building up the material and ideological wherewithal to contest U.S. primacy and leadership in the 21st Century. It continues to be among the foremost national security interests of the United States to prevent the domination of the Eurasian landmass by hostile powers.”

Last year, former Secretary of State RexTillerson in a speech in Washington named China as the cause for the US’s intensified interest in the Indian Ocean, and as the reason for its deepening defence ties with India.

‘Joining’ the Indian and Pacific Oceans at the conceptual level by using‘Indo-Pacific’terminology is but one of the devices serving US strategic interests in the IOR. The US has been strengthening naval ties with strategically located states, encouraging its allies to do likewise (joint exercises of the ‘Quad’ for example), renaming the Pacific Command as ‘Indo Pacific Command,’ etc., etc. But the littorals of the Indian Ocean would not want to be bullied by the US any more than the littorals of the South China Sea resent being bullied by China.

India-US strategic ties got a boost recently when the inaugural round of talks among their respective ministers of defence and foreign affairs (dubbed ‘2 + 2 talks’) culminated withadefence agreement in Delhi, hailed as a breakthrough by both parties. The COMCASA (Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement) signed after years of negotiationon Sept. 6th, would align India’s military communications systems with those of the US and facilitate ‘interoperability’ between their forces, according to reports. It is the second of three ‘foundational agreements’ the US expects to conclude with India, designated a ‘major defence partner’ of the US.

What is interesting is that the agreement was signed in spite of India having gone ahead with its deal with Russia to purchase S-400 missiles, according to reports, in defiance of US sanctions under a recent US law designed to punish third parties having dealings with its adversaries. Under the ‘Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act’ (CAATSA) as it is called, the US would impose penalties on countries buying oil from Iran or having military transactions with Russia. Thisrefusal to submit to US pressure has been praised by Indian analysts, who feared India’s foreign policy was tilting too much towards the US.The US would now have to find ways of granting India a waiver of sanctions, it would seem.

“.. the CAATSA provides an underpinning for the US’ global hegemony, which is far beyond its stated purpose of sanctioning Russia over the Crimea” wrote Melkulangara Bhadrakumar, commenting on the COMCASA on ‘Strategic Culture Foundation’ website. “Simply put, without India realizing it, a point will be reached when it gets “locked in” and becomes an ally of the US, playing second fiddle to Washington in its Indo-Pacific strategies” he warned.

Indian Analysts have also noted that Prime Minister Modi’s policy towards China has become more nuanced, particularly since his informal and cordial April summit with China’s President Xi Jinping in Wuhan. Senior Analyst at the IDSA (Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis) P. Stobdan referring to Modi’s keynote speech at the Shangri La dialogue in June noted that his remarks“seemed a calibrated move to prevent India falling into a dangerous geopolitical trap vis-à-vis US, Russia and China.” He said the speech was ‘welcomed by everyone including China.”

In Ha Noi last week, responding to a question from Indian defence analyst Nitin Gokhale on the ‘new Indo-Pacific structure,’ Prime Minister Wickremesinghereportedly said “We are Asian so we have a common identity, but I think the distinct nature of the Indian Ocean and the geo-politics of this ocean must function as it is and you can’t use the Pacific issues to cover the Indian Ocean issues. But together we can all work for a stable order and to ensure freedom of navigation.” It remains to be seen whether his optimism was warranted.

Source: Daily Mirror