Brazil and other Latin American progressive governments are on the defensive as U.S.-backed political movements employ “silent coup” tactics to discredit and remove troublesome leaders, writes Ted Snider.

By Ted Snider

Brazil keeps its coups quiet (or at least quieter than many other Latin American countries). During the Cold War, there was much more attention to overt military regime changes often backed by the CIA, such as the overthrow of Guatemala’s Jacobo Arbenz in 1954, the ouster of Chile’s Salvador Allende in 1973 and even Argentina’s “dirty war” coup in 1976, than to Brazil’s 1964 coup that removed President João Goulart from power.

Noam Chomsky has called Goulart’s government “mildly social democratic.” Its replacement was a brutal military dictatorship.

In more modern times, Latin American coups have shed their image of overt military takeovers or covert CIA actions. Rather than tanks in the streets and grim-looking generals rounding up political opponents – today’s coups are more like the “color revolutions” used in Eastern Europe and the Mideast in which leftist, socialist or perceived anti-American governments were targeted with “soft power” tactics, such as economic dislocation, sophisticated propaganda, and political disorder often financed by “pro-democracy” non-governmental organizations (or NGOs).

This strategy began to take shape in the latter days of the Cold War as the CIA program of arming Nicaraguan Contra rebels gave way to a U.S. economic strategy of driving Sandinista-led Nicaragua into abject poverty, combined with a political strategy of spending on election-related NGOs by the U.S.-funded National Endowment for Democracy, setting the stage for the Sandinistas’ political defeat in 1990.

During the Obama administration, this strategy of non-violent “regime change” in Latin America has gained increasing favor, as with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s decisive support for the 2009 ouster of Honduran President Manuel Zelaya who had pursued a moderately progressive domestic policy that threatened the interests of the Central American nation’s traditional oligarchy and foreign investors.

Unlike the earlier military-style coups, the “silent coups” never take off their masks and reveal themselves as coups. They are coups disguised as domestic popular uprisings which are blamed on the misrule of the targeted government. Indeed, the U.S. mainstream media will go to great lengths to deny that these coups are even coups.

The new coups are cloaked in one of two disguises. In the first, a rightist minority that lost at the polls will allege “fraud” and move its message to the streets as an expression of “democracy”; in the second type, the minority cloaks its power grab behind the legal or constitutional workings of the legislature or the courts, such as was the case in ousting President Zelaya in Honduras in 2009.

Both strategies usually deploy accusations of corruption or dictatorial intent against the sitting government, charges that are trumpeted by rightist-owned news outlets and U.S.-funded NGOs that portray themselves as “promoting democracy,” seeking “good government” or defending “human rights.” Brazil today is showing signs of both strategies.

Brazil’s Boom

First, some background: In 2002, the Workers’ Party’s (PT) Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva came to power with 61.3 percent of the vote. Four years later, he was returned to power with a still overwhelming 60.83 percent. Lula da Silva’s presidency was marked by extraordinary growth in Brazil’s economy and by landmark social reforms and domestic infrastructure investments.

In 2010, at the end of Lula da Silva’s presidency, the BBC provided a typical account of his successes: “Number-crunchers say rising incomes have catapulted more than 29 million Brazilians into the middle class during the eight-year presidency of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, a former trade unionist elected in 2002. Some of these people are beneficiaries of government handouts and others of a steadily improving education system. Brazilians are staying in school longer, which secures them higher wages, which drives consumption, which in turn fuels a booming domestic economy.”

However, in Brazil, a two-term president must sit out a full term before running again. So, in 2010, Dilma Rousseff ran as Lula da Silva’s chosen successor. She won a majority 56.05 percent of the vote. When, in 2014, Rousseff won re-election with 52 percent of the vote, the right-wing opposition Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB) went into a panic.

This panic was not just because democracy was failing as a method for advancing right-wing goals, nor was the panic just over the fourth consecutive victory by the more left-wing PT. The panic became desperation when it became clear that, after the PT had succeeded in holding onto power while Lula da Silva was constitutionally sidelined, he was likely returning as the PT’s presidential candidate in 2018.

After all, Lula da Silva left office with an 80 percent approval rating. Democracy, it seemed, might never work for the PSDB. So, the “silent coup” playbook was opened. As the prescribed first play, the opposition refused to accept the 2014 electoral results despite never proffering a credible complaint. The second move was taking to the streets.

A well-organized and well-funded minority whose numbers were too small to prevail at the polls can still create lots of noise and disruption in the streets, manufacturing the appearance of a powerful democratic movement. Plus, these protests received sympathetic coverage from the corporate media of both Brazil and the United States.

The next step was to cite corruption and begin the process for a constitutional coup in the form of impeachment proceedings against President Rousseff. Corruption, of course, is a reliable weapon in this arsenal because there is always some corruption in government which can be exaggerated or ignored as political interests dictate.

Allegations of corruption also can be useful in dirtying up popular politicians by making them appear to be only interested in lining their pockets, a particularly effective line of attack against leaders who appear to be working to benefit the people. Meanwhile, the corruption of U.S.-favored politicians who are lining their own pockets much more egregiously is often ignored by the same media and NGOs.

Removing Leaders

In recent years, this type of “constitutional” coup was used in Honduras to get rid of democratically elected President Zelaya. He was whisked out of Honduras through a kidnapping at gunpoint that was dressed up as a constitutional obligation mandated by a court after Zelaya announced a plebiscite to determine whether Hondurans wanted to draft a new constitution.

The hostile political establishment in Honduras falsely translated his announcement into an unconstitutional intention to seek reelection, i.e., the abuse-of-power ruse. The ability to stand for a second term would be considered in the constitutional discussions, but was never announced as an intention by Zelaya.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court declared the President’s plebiscite unconstitutional and the military kidnapped Zelaya. The Supreme Court charged Zelaya with treason and declared a new president: a coup in constitutional disguise, one that was condemned by many Latin American nations but was embraced by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

This coup pattern reoccurred in Paraguay when right-wing Frederico Franco took the presidency from democratically elected, left-leaning Fernando Lugo in what has been called a parliamentary coup. As in Honduras, the coup was made to look like a constitutional transition. In the Paraguay case, the right-wing opposition opportunistically capitalized on a skirmish over disputed land that left at least 11people dead to unfairly blame the deaths on President Lugo. It then impeached him after giving him only 24 hours to prepare his defense and only two hours to deliver it.

Brazil is manifesting what could be the third example of this sort of coup in Latin America during the Obama administration.

Operation Lava Jato began in Brazil in March of 2014 as a judicial and police investigation into government corruption. Lava Jato is usually translated as “Car Wash” but, apparently, is better captured as “speed laundering” with the connotation of corruption and money laundering.

Operation Lava Jato began as the uncovering of political bribery and misuse of money, revolving around Brazil’s massive oil company Petrobras. The dirt – or political influence-buying – that needed washing stuck to all major political parties in a corrupt system, according to Alfredo Saad Filho, Professor of Political Economy at the SAOS University of London.

But Brazil’s political Right hijacked the investigation and turned a legitimate judicial investigation into a political coup attempt.

According to Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Professor of Sociology at the University of Coimbra in Portugal and Distinguished Legal Scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, although Operation Lava Jato “involves the leaders of various parties, the fact is that Operation Lava Jato – and its media accomplices – have shown to be majorly inclined towards implicating the leaders of PT (the Workers’ Party), with the by now unmistakable purpose of bringing about the political assassination of President Dilma Rousseff and former President Lula da Silva.”

De Sousa Santos called the political repurposing of the judicial investigation “glaringly” and “crassly selective,” and he indicts the entire operation in its refitted form as “blatantly illegal and unconstitutional.” Alfredo Saad Filho said the goal is to “inflict maximum damage” on the PT “while shielding other parties.”

Neutralizing Lula

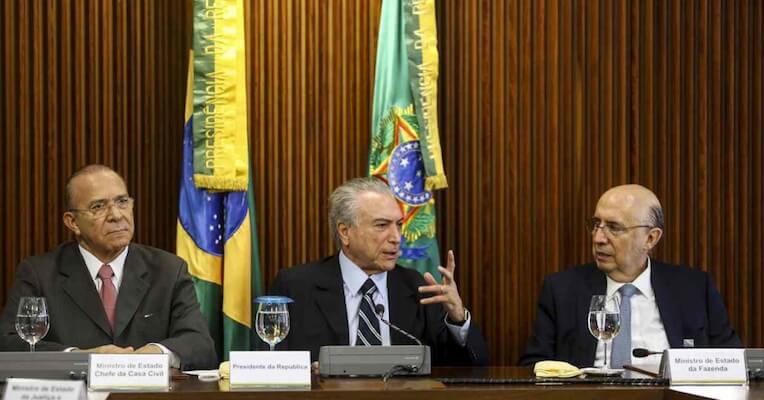

The ultimate goal of the coup in democratic disguise is to neutralize Lula da Silva. Criminal charges — which Filho describes as “stretched” — have been brought against Lula da Silva. On March 4, he was detained for questioning. President Rousseff then appointed Lula da Silva as her Chief of Staff, a move which the opposition represented as an attempt to use ministerial status to protect him from prosecution by any body other than the Supreme Court.

But Filho says this representation is based on an illegally recorded and illegally released conversation between Rousseff and Lula da Silva. The conversation, Filho says, was then “misinterpreted” to allow it to be “presented as ‘proof’ of a conspiracy to protect Lula.” De Sousa Santos added that “President Dilma Rousseff’s cabinet has decided to include Lula da Silva among its ministers. It is its right to do so and no institution, least of all the judiciary, has the power to prevent it.”

No “presidential crime warranting an impeachment has emerged,” according to Filho.

As in Honduras and Paraguay, an opposition that despairs of its ability to remove the elected government through democratic instruments has turned to undemocratic means that it hopes to disguise as judicial and constitutional. In the case of Brazil, Professor de Sousa Santos calls this coup in democratic disguise a “political-judicial coup.”

In both Honduras and Paraguay, the U.S. government, though publicly insisting that it wasn’t involved, privately knew the machinations were coups. Less than a month after the Honduran coup, the White House, State Department and many others were in receipt of a frank cable from the U.S. embassy in Honduras calling the coup a coup.

Entitled “Open and Shut: the Case of the Honduran Coup,” the embassy said, “There is no doubt that the military, Supreme Court and National Congress conspired on June 28 in what constituted an illegal and unconstitutional coup.” The cable added, “none of the . . . arguments [of the coup defenders] has any substantive validity under the Honduran constitution.”

As for Paraguay, U.S. embassy cables said Lugo’s political opposition had as its goal to “Capitalize on any Lugo missteps” and “impeach Lugo and assure their own political supremacy.” The cable noted that to achieve their goal, they are willing to “legally” impeach Lugo “even if on spurious grounds.”

Professor de Sousa Santos said U.S. imperialism has returned to its Latin American “backyard” in the form of NGO development projects, “organizations whose gestures in defense of democracy are just a front for covert, aggressive attacks and provocations directed at progressive governments.”

He said the U.S. goal is “replacing progressive governments with conservative governments while maintaining the democratic façade.” He claimed that Brazil is awash in financing from American sources, including “CIA-related organizations.” (The National Endowment for Democracy was created in 1983, in part to do somewhat openly what the CIA had previously done covertly, i.e., finance political movements that bent to Washington’s will.)

History will tell whether Brazil’s silent coup will succeed. History may also reveal what the U.S. government’s knowledge and involvement may be.