by Dec 28, 2021

Introduction

In the mainstream view, al-Qaeda did not play a role in the Syria conflict until Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi dispatched his deputy, Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, to Syria in August 2011 to establish a wing of the group there, called Jabhat al-Nusra, or the Nusra Front. Additionally, al-Qaeda allegedly did not carry out any military operations until December 2011 and did not announce its establishment until January 2012.

However, there is evidence that al-Qaeda affiliated militants were involved in the Syrian conflict much earlier. Saudi intelligence chief Prince Bandar bin Sultan, former Syrian Vice President Abd al-Halim Khaddam, and Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri all played key roles in dispatching al-Qaeda affiliated militants to Syria in the early stages of the conflict. They did so at the direction of U.S. and UK planners, who hoped to spark a sectarian civil war that would lead to regime change in Damascus.

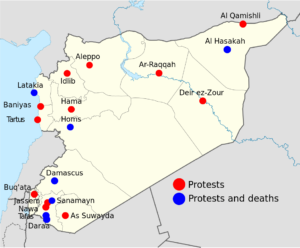

Militants from the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) were dispatched to Syria from neighboring Iraq starting in late 2010. Starting in March 2011, they began attacking Syrian security forces, police, and soldiers under the cover of anti-government protests. Militants from Fatah al-Islam were dispatched from Lebanon to Syria for the same purpose as early as April 2011. Militants from the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) began fighting in Syria in October 2011, after successfully toppling the Libyan government under the cover of NATO airpower. Additionally, there is evidence that the first protestors killed in Deraa on March 18, 2011 were killed by Salafist militants as part of a false flag attack, rather than by Syrian government security forces, as is commonly assumed.

In this essay, I review U.S. and UK efforts to partner with al-Qaeda affiliated groups to topple the Syrian government, and the role played by such militants in the first weeks and months of the 2011 Syrian conflict.

U.S. planners have long sought to topple the government of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. U.S. General Wesley Clark famously revealed that the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq was part of a larger plan developed by U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s office “to take out seven countries in five years,” including Iran, Libya, and Syria.

In December 2005, the Wall Street Journal reported that within U.S. government circles, the “Pressure for regime change in Damascus is rising,” and that according to prominent neoconservative and architect of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, Richard Perle, “Assad has never been weaker, and we should take advantage of that.” Perle, a member of the U.S. Defense Policy Board, made his comments in the context of a U.S.-sponsored effort to blame the Syrian government for the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri.

In March 2006, former Syrian vice president Abd al-Halim Khaddam partnered with Syrian Muslim Brotherhood leader Ali al-Bayanouni to form a new opposition group in exile, the National Salvation Front (NSF). In October 2006, several NSF members met with Michael Doran of the U.S. National Security Council, who was a close associate of prominent neoconservative and Bush administration official Elliott Abrams to discuss the possibility of regime change in Syria. Representatives of the NSF were also given a meeting with Saudi King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz the same month.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Elliott Abrams warmed to the idea of partnering with the Brotherhood after Iranian-backed Lebanese Hezbollah fought Israel to a standstill in the summer of 2006, which caused Washington to become “increasingly concerned about Syria’s military alliance with Iran, and the threat it posed to U.S. interests in the region.”

Hezbollah’s surprisingly strong performance during the 2006 war, coupled with the rise of Iranian influence in U.S.-occupied Iraq, prompted what journalist Seymour Hersh described as a “redirection” in U.S. policy in the Middle East. This massive shift in policy was led by then Vice President Dick Cheney, Abrams, and Saudi national security advisor and former ambassador to the U.S., Prince Bandar bin Sultan.

The redirection involved working with Washington’s Sunni regional client states “to counteract Shiite ascendance in the region.” As part of this effort, the “Saudi government, with Washington’s approval, would provide funds and logistical aid to weaken the government of President Bashir [sic] Assad, of Syria.” Hersh notes further, “There is evidence that the Administration’s redirection strategy has already benefitted the Brotherhood,” and that according to a former high-ranking CIA officer, Abd al-Halim Khaddam and the NSF were receiving both financial and diplomatic support from the Americans and Saudis. Hersh notes further that Vice President Dick Cheney had been advised by Lebanese politician, Walid Jumblatt, that “if the United States does try to move against Syria, members of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood would be ‘the ones to talk to.’”

Salafis Throwing Bombs

Hersh details further that the U.S. effort to topple the Syrian government would involve not only the Muslim Brotherhood, but also Salafist militant groups controlled by Saudi intelligence. According to a U.S. government consultant, “Bandar and other Saudis have assured the White House that ‘they will keep a very close eye on the religious fundamentalists. Their message to us was ‘We’ve created this movement, and we can control it.’ It’s not that we don’t want the Salafis to throw bombs; it’s who they throw them at—Hezbollah, Moqtada al-Sadr, Iran, and at the Syrians, if they continue to work with Hezbollah and Iran.”

In December 2006, the Charge d’Affaires of the U.S. embassy in Damascus, William Roebuck, had already acknowledged the possibility of exploiting Salafist militants to promote regime change in Syria. Roebuck wrote that, “We believe Bashar’s weaknesses are in how he chooses to react to looming issues, both perceived and real,” including “the potential threat to the regime from the increasing presence of transiting Islamist extremists. This cable summarizes our assessment of these vulnerabilities and suggests that there may be actions, statements, and signals that the USG can send that will improve the likelihood of such opportunities arising. These proposals will need to be fleshed out and converted into real actions and we need to be ready to move quickly to take advantage of such opportunities. [emphasis mine].”

We Have a Liberal Attitude

One reservoir of al-Qaeda-affiliated militants to be leveraged by U.S. planners was in the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli. Seymour Hersh notes that according to a 2005 International Crisis Group (ICG) report, pro-Saudi Lebanese politician, Saad Hariri (son of the assassinated Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri) had helped release four Salafist militants from prison who had previously trained in al-Qaeda camps in Afghanistan and were arrested in Lebanon while trying to establish an Islamic state in the north of the country. Hariri also used his influence in parliament to obtain amnesty for another 29 Salafist militants, including seven suspected of bombing foreign embassies in Beirut a year prior. Hersh notes as well that according to a senior official in the Lebanese government, “We have a liberal attitude that allows Al Qaeda types to have a presence here.”

Charles Harb of the American University of Beirut similarly observed in May 2007 that Saad Hariri was giving “political cover” to “radical Sunni movements.” Harb explains that to attract Sunni voters in the 2005 national parliamentary elections, Hariri had “pardoned jailed Sunni militants involved in violence in December 2000.” Harb also warned that “Courting radical Sunni sentiment is a dangerous game. Fear of Shia influence in Arab affairs has prompted many Sunni leaders to warn of a ‘Shia crescent’ stretching from Iran, through Iraq, to south Lebanon.” Harb also noted the involvement of Saudi intelligence in cultivating these groups. He explained that “Several reports have highlighted efforts by Saudi officials to strengthen Sunni groups, including radical ones, to face the Shia renaissance across the region. But building up radical Sunni groups to face the Shia challenge can easily backfire.”

Harb was writing in response to the eruption of violence in the Nahr al-Bared Palestinian refugee camp on May 19, 2007. The camp, located in northern Lebanon, had been occupied by militants from the al-Qaeda-affiliated group, Fatah al-Islam. Fighting had erupted between the militants and members of the Lebanese security forces, allegedly after an attempted bank robbery. The fighting left the camp almost entirely flattened and its Palestinian refugee population homeless.

Two months before the outbreak of violence in Nahr al-Bared, the New York Times had interviewed Fatah al-Islam’s leader, Shakir al-Abssi, a former associate of notorious al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. The NYT reports that, “Despite being on terrorism watch lists around the world, he has set himself up in a Palestinian refugee camp where, because of Lebanese politics, he is largely shielded from the government.” Major General Achraf Rifi, general director of Lebanon’s Internal Security Forces told the NYT that to enter the camp and detain al-Abssi, “We would need an agreement from other Arab countries.” In other words, al-Abssi was being shielded by Saad Hariri and Saudi intelligence.

America’s Jihadi University

Another reservoir of Salafist militancy from which U.S. and Saudi planners could draw was in Iraq, which had become the epicenter of the transnational jihadi movement after foreign militants flooded into the country to fight against U.S. occupation forces following the 2003 U.S. invasion. In 2004, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s insurgent group, al-Tawhid w al-Jihad, became the official al-Qaeda affiliate in Iraq. Starting in 2007, Sunni tribes and insurgent groups that had once fought alongside al-Qaeda against U.S. occupation forces became disillusioned by the terror group’s indiscriminate violence. Recognizing al-Qaeda as a bigger threat, they partnered with their former enemies in the U.S. military as part of the Awakening movement to fight the group. This led supporters of al-Qaeda to lament that the “people of Iraq completely betrayed the mujahids.”

Without a Sunni support base in Anbar, the majority of al-Qaeda militants were quickly killed or imprisoned. By 2009, al-Qaeda in Iraq (by that time known as the Islamic State of Iraq) had been all but defeated. Islam scholar and former State Department advisor William McCants observed that during this time al-Qaeda was on “life support,” and that fellow jihadists were mocking the group, describing it as a “paper state” because it lacked control of any territory.”

Though al-Qaeda was weak and in disarray on the battlefield, it was at the same time thriving within U.S. prisons, most notably in Camp Bucca, a U.S.-run detention facility in the south of the country, which held some 26,000 detainees at its height in 2007. According to Lt. Col. Kenneth Plowman, a spokesman for Task Force 134 which ran the prison, al-Qaeda members were effectively functioning as a gang within the camp’s walls, including operating “jail house sharia courts…despite the presence of U.S guards, to enforce an extreme interpretation of Islamic law. They were then used to convict moderate inmates, who were then tortured or killed.”

In 2008, Marine Major General Douglas Stone was tasked with running the facility. He concluded that Bucca had become a “jihadi university,” giving the al-Qaeda leadership the opportunity to recruit, organize and plan within the prison. General Stone conducted extensive screening to identify which prisoners did not pose a security threat and could be released, and which were extremists or “takfiris” that should be isolated from the broader prison population. He estimated that one third, roughly 8,000, constituted “genuinely continuing and imperative security risks.” The Independent reported in 2014 that according to the terrorism analyst firm the Soufan Group, “nine members of the Islamic State’s top command did time at Bucca.” Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, the future leader of the al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, the Nusra Front, was among those al-Qaeda leaders held in Camp Bucca. He was detained in 2006 and released by US officials in 2008.

An Islamic state member later told the Guardian, “We had so much time to sit and plan…It was the perfect environment. We all agreed to get together when we got out. The way to reconnect was easy. We wrote each other’s details on the elastic of our boxer shorts. When we got out, we called. Everyone who was important to me was written on white elastic. I had their phone numbers, their villages. By 2009, many of us were back doing what we did before we were caught. But this time we were doing it better.”

The Great Prison Release

Islamic State of Iraq militants were by this time “doing it better” because of what Craig Whiteside of the U.S. Naval War College dubbed, “the Great Prison Release of 2009.” 5,700 detainees were released from Bucca that year and Whiteside writes that, “An unknown number of these men were destined to return to ISI [Islamic State of Iraq], to execute operations as part of cells assembled during their time in Bucca.” Whiteside, himself a former US army infantry officer and Iraq war veteran, was puzzled by the release plan, which did not meet the usual preconditions for the early release of prisoners after a conflict, including that the “population must support the release.” He notes that support for the release of these militants was likely low, even among Iraq’s Sunnis, given that “the Awakening movement had conducted a skillful campaign to rally tribal allies and pacify militant members of their own tribes in order to dramatically reduce the violence in tribal areas, and the release of thousands of highly organized and committed ISI recruits from prison had a predictable impact on the Awakening groups’ ability to control Sunni areas beyond 2010.” Whiteside notes further that, “The United States is often unjustly blamed for many things that are wrong in this world, but the revitalization of ISIL [ISIS] and its incubation in our own Camp Bucca is something that Americans truly own…The Iraqi government has many enemies, and the United States helped put many of them out on the street in 2009. Why?”

The danger of such a policy was immediately apparent to Iraqi officials and was quickly reported by then Washington Post journalist Anthony Shadid. In March 2009, Shadid visited the town of Garma (al-Karma), some 16 kilometers from Falluja, a former al-Qaeda stronghold in Anbar province. Shadid asked the local police chief about the nature of the released detainees, who replied, “These men weren’t planting flowers in a garden. They weren’t strolling down the street,” when they were detained. The police chief admitted to being overwhelmed by the return of hundreds of former Bucca inmates to the area while estimating that 90% would return to the fight. The deputy police chief in Garma noted that the one-time driver of al-Zarqawi was among those who had been released and had already carried out a car bomb attack that had killed 15. An Iraqi ministry of interior official further told Shadid that “Al-Qaeda is preparing itself for the departure of the Americans. And they want to stage a revolution.”

Al-Qaeda Resurrected

Few understood at the time that this so-called revolution would be directed first at Syria instead of Iraq. CIA director John Brennan later acknowledged that al-Qaeda had been defeated in Iraq but was soon able to reconstitute itself under the shadow of the U.S. withdrawal by turning its attention toward Syria. Brennan noted in 2015 that the Islamic State “had its roots in al-Qaida in Iraq. It was, you know, pretty much decimated when U.S. forces were there in Iraq. It had maybe 700-or-so adherents left. And then it grew quite a bit in the last several years, when it split then from al-Qaida in Syria, and set up its own organization.”

With the dramatic rise of the Islamic State in Syria in 2014, the U.S. press acknowledged the U.S. role in incubating the group’s leadership in its own prisons, but claimed this was inadvertent, an accident resulting from ignorance. For example, the New York Times acknowledged in 2015 that Islamic State leader Baghdadi had indeed been held at Bucca in 2004, but that the United States had only “unintentionally create[d] the conditions ripe for training a new generation of insurgents [emphasis mine].”

There are several reasons to doubt that the prison release that led to the resurrection of al-Qaeda in Iraq in 2009 was unintentional, however. When asked by journalist Mehdi Hassan about U.S.-coordinated arms transfers to al-Qaeda affiliated groups in Syria in 2012, lieutenant general and former Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) head Michael Flynn responded “I will tell you, it goes before 2012. I mean, when we were, when we were in Iraq and we still had decisions to be made before there was a decision to pull out of Iraq in 2011. I mean, it was very clear what we were, what we were going to face [emphasis mine].”

As mentioned above, Saudi Prince Bandar bin Sultan had assured his U.S. counterparts that he controlled Salafist militant groups in the region (“We’ve created this movement, and we can control it”), and that these groups could be re-directed against what U.S. planners viewed as their now more significant foes, Iran, Syria, and Hezbollah. For Bandar to reconstitute a decimated al-Qaeda organization and unleash it in the direction of Syria as requested by U.S. planners, a large-scale release of U.S.-held prisoners of the sort seen in 2009 would have been needed.

The “redirection” embraced by U.S. planners in 2007 was therefore simply an adoption of previous Saudi policy, adopted by U.S. planners once they realized their strategic mistake of empowering Iran via their own invasion of Iraq.

Piss Outside the Tent, Not Inside the Tent

It may seem conspiratorial to suggest that al-Qaeda in Iraq and its later iterations were controlled by Prince Bandar, but Saudi support for the organization throughout the terror group’s evolution is no longer in question. As Iraq expert Joel Wing notes, Saudi support for al-Qaeda affiliated groups in Iraq by 2007 (the time of Hersh’s reporting) was already well documented. Wing notes that the Saudis were providing cash to al-Qaeda groups, and that some 40% of foreign fighters in Iraq were Saudis, as were 40% of the foreigners detained in US prisons such as Camp Bucca.

The U.S. military therefore found itself fighting an enemy in Iraq supported by its own close ally. This mirrored the situation in Afghanistan, where the U.S. military was fighting the Taliban, which was supported by the intelligence services of close U.S.-ally Pakistan.

U.S. officials were aware of the crucial Saudi role in stoking the Iraqi insurgency, and allegedly raised concerns about it with their Saudi counterparts in private, but chose to publicly focus blame on Syria and Iran instead. Wing notes that, “In April 2008 President Bush sent General David Petraeus and U.S. Ambassador to Iraq Ryan Crocker to Saudi Arabia to try to get them to support Iraq. The two U.S. emissaries were also supposed to discuss the Saudis’ role with the insurgency. Back in August 2007 the U.S. had a similar mission when Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice and Defense Secretary Robert Gates went to the kingdom to discuss the same topics. Earlier in that year the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Zalmay Khalizad had accused the Saudis of destabilizing Iraq with their backing of the insurgency. Both times the U.S. administration was rebuffed. Saudi officials admitted that their young people were going to Iraq, and said they were doing what they could to stop them but denied any role in fund raising for the insurgents. In 2006 the Iraq Study Group also mentioned the Saudi role, saying that the government was either passive about it or didn’t care.”

A leaked State Department cable from 2009 further reinforced the view that Saudi Arabia continued to be “a critical source of terrorist funding,” including for al-Qaeda. The cable stated that “While the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) takes seriously the threat of terrorism within Saudi Arabia, it has been an ongoing challenge to persuade Saudi officials to treat terrorist financing emanating from Saudi Arabia as a strategic priority.”

Joel Wing observes further that “The Saudis have four reasons for their policy. First, the Saudi kingdom opposed the U.S. invasion, and warned the Bush administration against it. Second, the Saudi elite rejected having a Shiite led government in Iraq. There are some ultra-religious Sunnis who do not believe that Shiites are real Muslims. Third, the Saudis felt that the combination of the American-led war and the ascendancy of Iraq’s Shiites would open the door to Iran, the Saudis main rival in the region.”

Saudi control over al-Qaeda likely extended at this time beyond the group’s franchise in Iraq, and to Osama bin Laden, himself. Seymour Hersh reports that “bin Laden had been a prisoner of the ISI [Pakistani intelligence] at the Abbottabad compound since 2006” and that Saudi Arabia “had been financing bin Laden’s upkeep since his seizure by the Pakistanis” until his killing by U.S. special forces in May 2011. This gave both the Saudis and Pakistanis leverage over the group’s albeit greatly diminished activities in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Though Saudi support for al-Qaeda is often blamed on private businessmen or religious charities, it is implausible that these private efforts would be possible without the knowledge, assistance, and approval of Saudi intelligence.

Writing for Vanity Fair, Anthony Summers and Robyn Swann detail the extensive evidence of Saudi state support for al-Qaeda stretching back decades. They cite former CIA officer John Kiriakou as explaining in 2002 that, “We had known for years…that Saudi royals—I should say elements of the royal family—were funding al-Qaeda.” The authors further quote former deputy homeland-security adviser to President Bush, Richard Falkenrath, as explaining that al-Qaeda was “led and financed largely by Saudis, with extensive support from Pakistani intelligence.”

Bin Laden’s British Connection

Britain provided another reservoir of al-Qaeda linked fighters that could be deployed to effect regime change in Syria on behalf of U.S. planners, courtesy of their counterparts in British intelligence.

It is often forgotten that Britain has long served as a haven for al-Qaeda affiliated groups. As journalist Mark Curtis observed in his book Secret Affairs: Britain’s Collusion with Radical Islam, “London had by [1998] become, along with Taliban-controlled Afghanistan which housed bin Laden, the principal administrative centre for global jihad, where authorities were, at the very least, turning a blind eye to terrorist activities launched from their soil.”

The Guardian reports that, “Bin Laden’s British connection dates back to the early 1990s, when he founded a London-based group, the Advisory and Reform Committee, that distributed literature against the Saudi regime.” Academic Christopher M. Davidson notes in his book Shadow Wars: the Secret Struggle for the Middle East that bin Laden visited the UK personally and considered applying for asylum there, while his London office “was designed both to publicize the statements of Osama bin Laden and to provide a cover for activity in support of al-Qaeda’s ‘military activities,’ including the recruitment of military trainees, the disbursement of funds and the procurement of necessary equipment including satellite telephones and necessary services,” per New York federal court documents indicting bin Laden for carrying out 9/11.

Several prominent jihadist theoreticians lived in London for extensive periods in the 1990’s, including Abu Musab al-Suri, viewed by many as the “architect of global jihad,” Abu Qatada, known as “al-Qaeda’s spiritual ambassador to Europe,” and long suspected of having links with British intelligence, and Abu Abdallah Sadiq.

Abu Abdallah Sadiq, better known as Abd al-Hakim Belhaj, was the founder of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG). Mark Curtis explains that the LIFG was formed in 1990 in Afghanistan by 500 Libyan jihadists then fighting the Soviet-backed Afghan government that then went on to fight with the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) against the Algerian government. According to the British Home Office, the LIFG’s “aim had been to overthrow the Qadafi regime and replace it with an Islamic State,” while the U.S. government described the LIFG as an “al-Qaeda affiliate known for engaging in terrorist activity in Libya and cooperating with al-Qaeda worldwide.” Curtis reports that in 1996, British intelligence partnered with the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) to carry out a failed assassination attempt against Libyan president, Colonel Muamar Qaddafi, and that prominent members of the group were allowed to establish a base for logistical support and fundraising on British soil. Curtis notes that the group’s communiques calling for the overthrow of the Libyan government were issued from London, where several prominent LIFG members were living after having received political asylum.

Another prominent Salafist theoretician living in London during this period was the Syrian preacher, Muhammad Sarour Zein al-Abedine. According to Raffaello Pantucci of the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, Muhammad Sarour was “One of the more under-reported but highly important figures to have emerged from the United Kingdom…A British passport holder, Surur was based in the United Kingdom for almost two decades after moving there in the 1980s…A former Muslim Brotherhood activist, Surur was an innovator in Salafist thinking and established with his followers the Center for Islamic Studies in Birmingham, from where he published magazines and later ran the www.alsunnah.org website.” Sarour was known for his anti-Shia sectarianism, and under a pseudonym wrote the book “Then Came the Turn of the Majus,” which inspired al-Qaeda in Iraq leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi to advocate genocide against the Shia in Iraq before his killing by US occupation forces in 2006.

Sarour’s role in the early days and weeks of the 2011 Syrian conflict will be discussed below. It should be noted here that according to Pantucci, Sarour would later establish “himself as one of the key conduits for Qatari money to the anti-Assad rebels.”

Convoys of Murder

As detailed by Mark Curtis, U.S. and UK intelligence relied on young men from Britain’s Salafist community to fight in the war in Bosnia in the early 1990’s. This was later acknowledged even in the mainstream UK press. Labour MP Michael Meacher wrote in 2005 in the Guardian that, “During the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s, the U.S. funded large numbers of jihadists through Pakistan’s secret intelligence service, the ISI. Later the U.S. wanted to raise another jihadi corps, again using proxies, to help Bosnian Muslims fight to weaken the Serb government’s hold on Yugoslavia. Those they turned to included Pakistanis in Britain.”

British jihadi recruits and weapons were smuggled into Bosnia under the pretext of humanitarian aid efforts, specifically through “Convoys of Mercy.” In one notable case, British-Pakistani and London School of Economics graduate Omar Saeed Sheikh joined an aid convoy to Bosnia, which he acknowledged in his journal was for “organising clandestine support for the Muslim fighters.” Upon reaching the Croatian port town of Split, near the Bosnian border, Sheikh joined a jihadist group called the Harakut-ul- Mujaheddin (HUM) and was sent to Pakistan for training. Sheikh was later convicted of kidnapping Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl in Pakistan. Pearl was beheaded and his death captured on video. As noted by the Guardian, Sheikh also wired $100,000 to 9/11 hijacker Muhammad Atta, at the behest of Pakistan’s intelligence service.

In the late 1990’s, British intelligence also dispatched British-Pakistani Jihadis to Kosovo under the cover of humanitarian convoys to continue the war against Serbia. Labour MP Meacher writes further that, “For nearly a decade the U.S. helped Islamist insurgents linked to Chechnya, Iran and Saudi Arabia destabilise the former Yugoslavia. The insurgents were also allowed to move further east to Kosovo,” and that “the former US federal prosecutor John Loftus reported that British intelligence had used the al-Muhajiroun group in London to recruit Islamist militants with British passports for the war against the Serbs in Kosovo.”

The al-Muhajiroun group was established in 1996 in Britain by Syrian cleric Omar Bakri Mohammed, who, as journalist Nafeez Ahmed details, was a long-time informant for British intelligence, meeting regularly with MI5 agents throughout the 1990’s. Bakri himself acknowledged his role in training jihadists to be dispatched abroad. He explained to the Guardian in May 2000 that al-Muhaijiroun has a network of centers around the world, divided into two wings: “There is the Da’wah (propagation) network, and there is the Jihad Network.” The Guardian notes that Bakri “admitted that there is a global network of agents with connections to the military camps, some of whom work from Britain.”

Al-Muhajiroun founder al-Bakri left Britain for Lebanon one month after the 7/7 attacks in July 2005, in which suicide bombers targeted the London transit system, killing 52. Although former al-Muhajiroun members participated in the attack, British officials did not prevent Bakri from leaving Britain. By 2009, Lebanese security forces were accusing Bakri of training al-Qaeda members, while Bakri himself boasted, “Today, angry Lebanese Sunnis ask me to organize their jihad against the Shi’ites…Al-Qaeda in Lebanon…are the only ones who can defeat Hezbollah.”

Seek and Destroy

In 2009, the same year in which U.S. planners were helping to resurrect al-Qaeda in Iraq, French Foreign Minister Roland Dumas was told by top British officials that “they were preparing something in Syria…Britain was organizing an invasion of rebels into Syria. They even asked me, although I was no longer minister for foreign affairs, if I would like to participate.” When asked why the British would undertake such a plan, Dumas responded, “it’s important to understand, that the Syrian regime makes anti-Israeli talk,” and that he had previously been told by an Israeli prime minister that the Israelis would “seek to ‘destroy’ any country that did not ‘get along’ with it in the region.”

It is doubtful that UK planners would undertake such a project without guidance from their U.S. counterparts. This suggests that UK efforts to organize “an invasion of rebels into Syria” was part of the broader U.S. effort to promote regime change in the country. Dumas did not indicate, or perhaps did not know, who exactly would constitute the so-called rebels that would invade Syria. It appears however that British officials speaking to Dumas were referring to militants from both the LIFG and al-Muhajiroun, given the groups’ long histories of cooperation with British intelligence.

The rebel army referred to by Dumas was first dispatched not to Syria, but to Libya, at the start of the so-called Arab Spring in 2011.

LIFG activities had been harshly curbed in 2004 after the “Deal in the Desert” between then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Qaddafi led to rapprochement between the two countries. The British government then placed the LIFG on its terror list in 2005 and assisted in the rendition of two senior LIFG leaders, Belhaj and Sami al-Saadi, to Libya. The British security services allowed other LIFG members to remain in the UK but placed them under surveillance, house arrest, or detention.

However, British foreign policy regarding Libya pivoted against Qaddafi once again in 2011. Middle East Eye (MEE) reports that according to Ziad Hashem, an LIFG member granted asylum in Britain, “When the revolution started, things changed in Britain.” MEE reports further that “The British government operated an ‘open door’ policy that allowed Libyan exiles and British-Libyan citizens to join the 2011 uprising that toppled Muammar Gaddafi.” LIFG members under counter-terrorism control orders in Britain were allowed to travel to Libya with “no questions asked,” and many had their passports returned to them for this purpose. One British-Libyan speaking with MEE explained that “These were old school LIFG guys, they [the British authorities] knew what they were doing..The whole Libyan diaspora were out there fighting alongside the rebel groups.” Another “described how he had carried out ‘PR work’ for the rebels in the months before Gaddafi was overthrown and eventually killed in October 2011. He said he was employed to edit videos showing Libyan rebels being trained by former British SAS and Irish special forces mercenaries in Benghazi, the eastern city from where the uprising against Gaddafi was launched.”

LIFG leader Belhaj had himself been released from prison by Libyan authorities in 2010 as part of a reconciliation deal arranged by Qaddafi’s son Saif al-Islam. With the start of the UK-backed Islamist insurgency in 2011, Belhaj commanded the Tripoli Brigade, which played a key role in toppling the Libyan government on behalf of NATO, spearheading the ground assault on the Libyan capital.

The Tripoli Brigade was itself formed by Mahdi al-Herati, who lived for 20 years in exile in Ireland, and had fought against U.S. occupation forces in Iraq in 2003. Herati returned to Libya at the outset of anti-government protests in February 2011 and partnered with his Irish-born brother-in-law, Husan al-Najar and other Libyan exiles to organize the Tripoli brigade. According to fellow anti-government fighters, Herati’s group received assistance from French, Qatari, and CIA intelligence officers. Both Herati and al-Najar would go on to fight in Syria in 2011, as discussed further below.

Once the NATO-backed campaign to topple Qaddafi in 2011 was successful, Herati, al-Najar and other Libyan LIFG exiles were dispatched to fight in Syria, as will be discussed below.

Pockets and Bases on Both Sides

In the lead up to the so-called Arab Spring, the interests of U.S. planners were aligned with those of the al-Qaeda groups in Iraq under Saudi control, making cooperation against the Syrian government beneficial for both parties.

A 2012 U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) document noted for example that “AQI [al-Qaeda in Iraq] supported the Syrian opposition from the beginning, both ideologically and through the media. AQI declared its opposition of Assad’s government because it considered it a sectarian regime targeting Sunnis [Emphasis mine].” The document notes further that AQI spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani “declared the Syrian regime as the spearhead of what he is naming Jibha al Ruwafidh (Forefront of the Shiites) because of its (the Syrian regime) declaration of war on the Sunnis.”

A more common translation of Jibha al-Ruwafidh is the “Rejectionist Front,” with “rejectionist” being a derogatory reference to Shiites. The “Rejectionist Front” concept identified by al-Adnani parallels the “Shiite Crescent” feared by U.S. and Saudi planners, and which spurred the 2007 “redirection” of US policy as reported by Seymour Hersh.

The DIA document notes further that “AQI had major pockets and bases on both sides of the [Iraq-Syria] border to facilitate the flow of materiel and recruits. There was a regression of AQI in the western provinces of Iraq during the years 2009 and 2010; However, after the rise of the insurgency in Syria, the religious and tribal powers in the regions began to sympathize with the sectarian uprising. This (sympathy) appeared in Friday prayer sermons, which called for volunteers to support the Sunnis in Syria.”

In other words, the infrastructure was in place (pockets and bases on both sides of the border) before the eruption of protests in March 2011 for al-Qaeda in Iraq, under Saudi instruction, to launch the anti-government insurgency.

Leaders of the Jihad

American journalist Theo Padnos, who was a captive of the Nusra Front for two years, including after Nusra split from the Islamic State and the two groups became rivals, pointed to al-Qaeda’s early involvement in the Syria conflict. Padnos explained that the “ISIS [Islamic State] commanders and foot soldiers with whom I was sometimes imprisoned believed that their leaders, directing matters from planning rooms in Anbar Province in Iraq, dispatched fighters into Syria in late 2010, long before any child in Deraa scrawled his graffiti on a schoolyard wall.”

Padnos explained further that, “in probably late 2010, before all the demonstrations in Deraa, at the very beginning of things, before the beginning of things, they made this point to me often, they came into Syria in order to destroy the country…They wanted to basically topple the government. And at the same time there was a wave of demonstrations sweeping the country. These al-Qaeda people from Iraq infiltrated as many demonstrations as they could. And with the weapons they brought into Syria from Iraq they started shooting at the police and they started murdering the police officers and surrounding the police stations and throwing smoke bombs and waiting until the police guys come out and then shooting the policemen and then capturing the weapons and going off to the next police station. They told me about this from the beginning, they are very proud of this. They do not believe that the Syrian revolution really began with demonstrations. For them, it began because they made it begin by killing the police officers. They were the ones who launched the whole thing. It’s important for them to feel it’s a jihad and they are leaders of the jihad.”

Syria’s First al-Qaeda Franchise

The early military involvement of al-Qaeda affiliated fighters in the so-called revolution is further confirmed by the fact that the first declared armed group to begin fighting the Syrian government was a Salafist militia known as the Islamic Movement of the Free Men of the Levant, or Ahrar al-Sham. Rania Abouzeid of Time Magazine reported that according to one fighter from Ahrar al-Sham, the group “started working on forming brigades ‘after the Egyptian revolution…well before March 15, 2011, when the Syrian revolution kicked off with protests in the southern agricultural city of Dara’a.”

Writing in Al-Monitor, Syrian journalist Abdullah Suleiman Ali also indicates that Ahrar al-Sham was active in the early months of the uprising. He reports that according to his source within the group, a number of foreign fighters, “including Saudis, were in Syria as the Ahrar al-Sham movement was emerging, i.e., since May 2011.” Suleiman notes that these Saudi fighters joined Ahrar al-Sham based on recommendations from senior al-Qaeda figures, and that long time al-Qaeda operative and former Fighting Vanguard member Abu Khalid al-Suri played an important role in establishing the group. Opposition activist and later McClatchy journalist Mousab al-Hamadee explained that “One of my friends who is now a rebel leader told me that the moment the group announced itself in 2011 it got a big bag of money sent directly from Ayman al Zawahiri, the leader of al Qaida.” As noted above, Saudis constituted the largest contingent of foreign militants fighting for al-Qaeda in Iraq, and were among the prisoners released by US forces from the prison at Camp Bucca in 2009.

Elements From Outside

The first major protests in Syria as part of the so-called Arab Spring erupted on March 18, 2011. After Friday prayers in the southern Syrian town of Deraa, a crowd of protestors marched from the al-Omari Mosque to the Political Security office of Atef Najib. Reuters claims that three men, Wissam Ayyash, Mahmoud al-Jawabra, and Ayhem al-Hariri “were killed when security forces opened fire on Friday on civilians at a peaceful protest demanding political freedoms and an end to corruption in Syria.” BBC Arabic similarly claimed that according to sources in Daraa, “four demonstrators were killed by security forces during a peaceful demonstration demanding political freedom and an end to corruption.” Pro-opposition Zaman al-Wasl claimed as well that the Syrian “regime did not tolerate protests opposing its rule and opened live fire directly on the protestors” killing Mahmoud al-Jawabra and three of his relatives.”

A closer look at events in Deraa suggests that the above descriptions provide a distorted view of what happened that day. Syrian security forces did not simply open fire on peaceful protestors to crush dissent as suggested above. Instead, they were responding to a chaotic situation that included mixture of peaceful protests and violent rioting. Further, there is evidence that al-Qaeda militants may have played a role in the killing of the first protestors on March 18 as part of a false flag operation.

In contrast to Western and opposition media reporting of events in Deraa on March 18, 2011, Syrian state media claimed that “During a gathering of citizens in Daraa province near the Omari Mosque on Friday afternoon, some infiltrators took advantage of this situation and caused chaos and riots,” while claiming that infiltrators had “inflicted damage on public and private property, and destroyed and burned a number of cars and public shops, which necessitated the intervention of policemen to ensure the safety of citizens and property. The rioters assaulted the police before being dispersed.”

The government version of events is of course likely to be biased. However, Muhammad Jamal Barout, associate researcher at the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in Qatar, provides a rather detailed account of the protest on March 18 that broadly supports the account provided by Syrian state media. Based on his interview with al-Jazeera’s then Damascus bureau chief, Abdul Hamid Tawfiq. Barout writes that “protestors, with the families of the children [who were detained for writing anti-regime graffiti on a school wall] at the front, headed towards the al-Omari mosque. They chanted ‘Where are you, oh people of al-Faz’a’ and ‘God, Syria, freedom, that’s all’ and ‘There is no fear after today,’ and they also chanted against the head of the political security branch, Atef al-Najib and against the governor Faisal Kalthum, and against business tycoon Rami Makhlouf…Then they headed to the political security branch building to burn it down. After about two hours, at about three thirty in the afternoon, four helicopters arrived that had been called in by the head of the security branch, and they were carrying counter-terrorism soldiers dressed in all black [my emphasis].”

Sheik Ahmed Siyasna, imam of the al-Omari mosque, gave credibility to the state media version of events, telling the government-run Tishreen newspaper that, “There were elements from outside Dara’a determined to burn and destroy public property…These unknown assailants want to harm the reputation of the sons of Hauran…The people of Dara’a affirm that recent events are not part of their tradition or custom.” It is possible that supporters of Siyasna instigated the rioting, and that Siyasna was simply blaming the violence on unknown, outside elements to shield his own supporters from blame, but he does not deny that violent rioting occurred.

The violence, whether by local or outside elements, continued in subsequent days. The Israel National News reported just two days later that over the weekend not only four protestors but also “seven police officers were killed, and the Baath Party Headquarters and courthouse were torched, in renewed violence on Sunday.”

It is not surprising that Syrian security forces would intervene to prevent public buildings from being burned down, both to prevent the destruction of public property generally and to safeguard the lives anyone inside.

Subsequent protests illustrate the dangers involved in situations of this sort, where events can quickly spin out of control. Three are worth highlighting here. During an anti-government protest on June 4, 2011, armed protestors threw an incendiary device inside the front doors of the post office in the northern Syrian town of Jisr al-Shagour, setting it on fire and burning 8 people to death inside. Two days later, on June 6, 2011, protestors in the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in the Damascus suburbs attempted to burn down the headquarters of a pro-Syrian government Palestinian political party, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine—General Command (PFLP-GC). In the process, one PFLP-GC official was stabbed to death by protestors and a PFLP-GC guard was burned to death inside the building, while PFLP-GC guards shot and killed two protestors. On February 18, 2011, during the first days of anti-governments protests in Libya, protestors in the eastern city of Derna burned to death several government supporters after locking them in holding cells in the local police station, and then setting it on fire.

Responding to Protestors’ Demands

Amidst the chaos in Deraa on Friday March 18, 2011 the Syrian government attempted to diffuse the situation by sending a top government official from Damascus to negotiate with a group of prominent Deraa elders representing the protesters, led by Sheikh Siyasna. Barout writes further that, “At the same time, a high-level political delegation arrived, led by Hisham Ikhtiyar, head of the office of National Security, who was known for dealing with crises and putting out fires. The central security committee, led by Ikhtiyar, agreed with the elders of Deraa on 13 points, foremost among them the resignation of the political security head [Atef al-Najib] and the governor of Deraa [Faisal Kalthum]. Ikhtiyar also agreed to expel the companies of Rami Makhlouf from Deraa, apologize to the local people, and allow a meeting between Deraa’s elders and president Bashar al-Assad, and also to political reform, and more freedoms, and the return of teachers who wear the niqab to their teaching posts, and to repeal unjust laws regarding the buying and selling of land, such as law 48 and law 26, and to lower the prices of fuel, and to some other local demands. Ikhtiyar further informed the elders of Deraa that the president [Bashar al-Assad] had agreed to these demands, and the people now awaited them being carried out.”

The Motorcycle Men

The efforts of Ikhtiyar and Siyasna to calm the situation were soon sabotaged, however. Barout reports that according to Abd al-Hamid Tawfiq, the Damascus bureau chief of al-Jazeera, “a few hours after the agreement between Ikhtiyar and Siyasna, a group of masked militants riding motorcycles opened fire on the demonstrators, killing four people between the hours of six and eight in the evening, including Ahmad al-Jawabra, who was considered the first martyr.”

And who were the masked militants riding motorcycles? Barout takes for granted they were from the government side. It is far from clear this is the case, however. Even if the government wished to suppress the protests with violence, it is likely it would have used either the counter terror forces that had arrived earlier that day from Damascus or local plain clothes security men (known by opposition supporters as shabiha) to confront and disperse the protestors. For example, plain clothes security men beat protestors to disperse a small demonstration outside the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus on the same day. It is unclear why the government would instead resort to using masked men on motorbikes in Deraa.

One possibility is that the masked men on motorcycles were “saboteurs” or “infiltrators” from a third party. Subsequent events also show that armed Salafist militants commonly used motorbikes to conduct hit and run attacks against the Syrian security forces and army, which raises the possibility that the killers of the first protestors on March 18 were saboteurs from a third party of this sort.

Evidence of Salafist militants using motorbikes to carry out attacks in this way comes not only from pro-government, but also independent, and opposition sources. For example, on April 19, 2011 al-Jazeera reported that “The Syrian Interior Ministry issued a circular in Homs governorate to prevent the entry of motorbikes into the city, ‘because some armed groups in the province implement their criminal plans using motorbikes.’” On the same day, the pro-government Akhbariya news channel claimed that “masked men” riding in “GMC vehicles and on motorcycles” opened fire on a funeral tent, shooting at both civilians and the security forces and police, injuring 11 policemen.

On May 5, 2011, the Christian Post reported that International Christian Concern, a Christian advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. “says that protesters are being led by hardline Islamists and that Christians have come under pressure to either join in protests demanding the resignation of President Bashir Assad, or else leave the country,’” and that “Eyewitnesses report seeing around 20 masked men on motorcycles open fire on a home in a Christian village outside Dara’a, in southern Syria.”

Muhammad Jamal Barout himself notes that on June 3, 2011 tens of masked young men from the area of Jabal al-Zawiya in Idlib province arrived in the town of Jisr al-Shagour on motorcycles with weapons they had purchased on the black market or had captured from government caches. These men were among those that attacked the Popular Army headquarters in the town to capture additional weapons. Two days later, on June 5, opposition militants attacked the local post office and military security headquarters, leading to a 36-hour gun battle. Opposition militants then ambushed a Syrian army convoy coming to Jisr al-Shagour as reinforcements, killing some 120 soldiers.

Human Rights Watch, which has links to the U.S. government and is supportive of the Syrian opposition, reported that an opposition activist witnessed a protest in Homs city on July 8, 2011 in which “several defectors showed up on motorcycles and killed 14 or 15 members of the security forces using Kalashnikovs and pump-action shotguns.”

Unknown Assailants

Opposition sources also acknowledged the possibility of saboteurs and infiltrators playing a role in early events of the uprising. As mentioned above, Sheikh Siyasna also acknowledged there were “unknown assailants” present at the protest on March 18 in Deraa who were “determined to burn and destroy public property.” Journalist Alix Van Buren of Italy’s la Repubblika newspaper reported on April 13, 2011 that “several Syrian dissidents believe in the presence and the role of ‘infiltrators.’ Michel Kilo [prominent opposition intellectual], though he accepts that possibility, cautioned that the issue of ‘infiltrators and conspiracies’ should not be exploited as an obstacle in the quick transition towards democracy.”

Additionally, the claim that the first protestors were killed in Deraa by militants on motorcycles, rather than by Syrian security forces or riot police comes from an against interest source, namely an al-Jazeera journalist. The Qatari-owned channel had a clear agenda to demonize the Syrian government, in cooperation with U.S. planners. Because of the editorial line of his employer, Abd al-Hamid Tawfiq was incentivized to relay a story that blamed the government for the first killings, but instead made a claim, at least privately, that would appear to exonerate the Syrian government and suggest the possibility of false flag killings.

Interestingly, Tawfiq resigned from his post in May 2011, citing only vague “pressures,” which many assumed to be coming from the Syrian government side. However, this period would see several prominent al-Jazeera journalists resign from the channel to protest what they viewed as coverage that was biased against the Syrian government and in favor of the Muslim Brotherhood. On April 24, 2011 Ghassan Bin Jeddo, the head of al-Jazeera’s Beirut office resigned because of the channel’s “alleged abandonment of professional and objective reporting, as it became ‘an operation room for incitement and mobilization.’” Al-Jazeera journalist Ali Hashem resigned in 2012, citing the channel’s censorship of his Syria reporting during this early period, which revealed armed groups crossing from Lebanon into Syria in late April 2011 (discussed in detail below). Beirut bureau chief Hassan Shaaban resigned shortly after Hashem.

It’s A Sabotage

But why would saboteurs from a third party want to kill protestors during the first major day of anti-government protests, in Deraa on March 18? If protestors were killed during a demonstration, and the deaths could be attributed to the security forces, this would help turn locals in Deraa, traditionally considered a Ba’athist stronghold, against the government.

Killing protestors right at this critical juncture and blaming it on the government would also sabotage Sheikh Siyasna’s efforts to win concessions from the government through negotiations, in exchange for putting an end to the protests and rioting. As noted above, Abd al-Hamid Tawfiq of al-Jazeera reported the first protesters were killed “a few hours after the agreement between Ikhtiyar and Siyasna,” the perfect time to ensure any agreement between the two sides would fall apart. The father of one of the boys detained and tortured for writing the graffiti on the school wall in Deraa one month before indicated that the conflict could have been resolved peacefully, but that as the deaths of protestors mounted, “People became uncontrollable.”

An end to the protests in exchange for government efforts to answer local grievances and demands for reform was a disaster scenario for hardline elements of the opposition, who demanded the “fall of the regime” and wanted “revolution” from the start. This attitude was evidenced when local supporters of the exiled Salafist preacher Muhamad Sarour later accused Sheikh Siyasna of treason for his willingness to negotiate with the government and call for calm, and pressured Siyasna to radicalize his position, which he refused to do. Sheikh Anas Sweid, a pro-opposition Sunni cleric from Homs, similarly stated a few weeks later that any clerics who stood against “the street” by cooperating with the government to end protests would be attacked, and therefore they had no ability to calm the protestors, as government officials had demanded of them.

Hidden Parties

There are several possibilities then, to account for the deaths of the first four protestors of the uprising on March 18, 2011. One possibility is that, as the opposition claims, the protestors were killed in an unprovoked manner by Syrian security forces during a completely peaceful protest. Another is that, as the government claims, they were killed by infiltrators or saboteurs from Salafist armed groups (including foreign al-Qaeda militants) who wished to sabotage any agreement to end the crisis, and to turn Deraa’s residents against the government. A final possibility is that the first protestors were killed in the chaos that resulted when protestors were rioting and tried to burn down the political security branch building, which Syrian security forces were trying to prevent.

If the first protestors were indeed killed by Syrian security forces, this played into the hands of opposition activists, who needed people to get killed to bring people into the streets against the government. If instead the security forces had orders not to open fire and did not kill the protesters as the government claims, Salafist militants on motorcycles made sure people were killed anyway to falsely blame the government and to provide the spark needed for further protest.

That four police officers were killed on the third day of protests and riots (Sunday March 20) is particularly significant, given claims by Islamic State members to Theo Padnos that the group was infiltrating protests and killing police officers during this early period.

It should be noted here that there was significant confusion, even among locals in Deraa, whether pro-opposition or pro-government, about who was killing who during this early period. Just being present in Deraa at the time, including at a protest where killings took place, does not necessarily mean one could determine the source of the violence. Additionally, first impressions can change once more evidence emerges.

For example, in 2014 Sharmine Narwani interviewed a “member of the large Hariri family in Daraa, who was there in March and April 2011, [who] says people are confused and that many ‘loyalties have changed two or three times from March 2011 till now. They were originally all with the government. Then suddenly changed against the government—but now I think maybe 50% or more came back to the Syrian regime’…The province was largely pro-government before things kicked off. According to the UAE paper The National, ‘Daraa had long had a reputation as being solidly pro-Assad, with many regime figures recruited from the area.’ But as Hariri explains it, ‘there were two opinions’ in Daraa. ‘One was that the regime is shooting more people to stop them and warn them to finish their protests and stop gathering. The other opinion was that hidden militias want this to continue, because if there are no funerals, there is no reason for people to gather.’ ‘At the beginning 99.9 percent of them were saying all shooting is by the government. But slowly, slowly this idea began to change in their mind – there are some hidden parties, but they don’t know what,” says Hariri, whose parents remain in Daraa.”

Mysterious Attacks

Summarizing the situation in Syria as of one month after the beginning of anti-government protests, Muhammad Jamal Barout writes, “There were signs of an initial and simple armament process for some groups of young men, ‘mysterious’ attacks on some army and police units, and the emergence of some Salafi players abroad, especially the ‘Sarourists,’ who have bases of influence among the youth of Houran, to develop the protest movement into an overall revolution against the regime.”

But who were the “hidden militias” carrying out these “mysterious attacks,” including potentially the killing of the four protestors on March 18? Barout’s observation that supporters of Muhummad Sarour wished to “develop the protest movement into an overall revolution” suggest his supporters may have been among the early armed elements in Deraa. As noted above, Sarour, who spent 20 years in Britain, emerged as “one of the key conduits for Qatari money to the anti-Assad rebels.”

This may explain the attack on Syrian security forces in the town of Nawa, near Deraa, on April 22, 2011. Human Rights Watch (HRW) confirmed that seven members of the security forces were shot to death under the cover of protests that day. The witness cited by HRW tries to emphasize the peaceful nature of the protestors, claiming they approached the local political security building holding olive branches to demand the release of two detainees. He nevertheless acknowledges that some of the protestors were at least lightly armed, and that once the protestors succeeded in storming the building, “they saw seven members of the security who had apparently been shot and killed by the protesters during the confrontation.” That more presumably heavily armed political security men (seven) died in the confrontation than protestors (four) suggests that well-armed militants had infiltrated the protest to attack the security forces, and that the four dead protestors may instead have been armed militants. This would align with claims made by al-Qaeda militants to Theo Padnos, and such a scenario was repeated several times in subsequent weeks elsewhere in Syria as I discuss below.

Additionally, there evidence pointing not only to the possibility of local Salafist militants carrying out such attacks, but also to foreign terrorist elements affiliated with al-Qaeda. We have evidence of an al-Qaeda attack near Deraa, just four weeks after the eruption of protests there. This comes from the Indian ambassador to Syria, V.P. Haran, who noted that on April 18, 2011 Syrian media reported that between 6 and 8 Syrian soldiers were killed when an armed group raided two security posts on the road between Damascus and the Jordanian border. After visiting the area two days later and speaking with locals, Haran had the impression that something even more serious had taken place. U.S. Ambassador to Syria Robert Ford and the Iraqi Ambassador to Syria both expressed their view in private conversations to Haran that the Syrian security forces had not only been killed, but beheaded, and that al-Qaeda in Iraq was responsible for the killings.

According to Haran, al-Qaeda had carried out attacks even earlier as well, on March 25 in Latakia. Syrian government sources claimed that twelve people were killed in Latakia that weekend, including security personnel, after unidentified gunmen shot at crowds from rooftops.

Firing Up the Old Sunni Network

The al-Qaeda leadership was not acting independently in preparing for a so-called revolution in Syria. As mentioned above, Seymour Hersh reported in 2007 that Prince Bandar bin Sultan had planned to deploy Salafist militants to undermine the Syrian government as part of the broader U.S. redirection in policy to “counteract Shiite ascendance,” and that Saudi officials had assured US planners that, “We’ve created this movement, and we can control it.”

Former Bush Administration official and neoconservative John Hannah also alluded to Bandar’s control of a Salafist militant network being directed at Syria just days after the al-Qaeda attack noted by V.P. Haran and encouraged his successors in the Obama administration to partner with Bandar to achieve U.S. goals in Syria. Hannah wrote in Foreign Policy on April 22, 2011 that “no one can discount the danger that, with its back against the wall, the [Saudi] Kingdom might once again fire up the old Sunni network and point it in the general direction of Shiite Iran,” and that “Bandar working without reference to U.S. interests is clearly cause for concern. But Bandar working as a partner with Washington against a common Iranian enemy is a major strategic asset. Drawing on Saudi resources and prestige, Bandar’s ingenuity and bent for bold action could be put to excellent use across the region in ways that reinforce U.S. policy and interests: through economic and political measures that weaken the Iranian mullahs; undermine the Assad regime.”

Using Tanks Against Protestors?

Because Salafist militants, including militants from al-Qaeda, were infiltrating protests and attacking Syrian soldiers and police, the opposition and Western press were able to falsely conflate the government’s military operations against these militants with efforts to respond to peaceful protests.

For example, Anthony Shadid of the New York Times reported on April 25, 2011 that “A handful of videos posted on the Internet, along with residents’ accounts, gave a picture of a city under broad military assault, in what appeared to mark a new phase in the government crackdown. Tanks had not previously been used against protesters, and the force of the assault suggested that the military planned some sort of occupation of the town [emphasis mine].” Shadid quoted a Deraa resident as claiming, ‘It’s an attempt to occupy Dara’a,” and that “soldiers had taken three mosques, but had yet to capture the Omari Mosque, where he said thousands had sought refuge. Since the beginning of the uprising last month, it has served as a headquarters of sorts for demonstrators. He quoted people there as shouting, ‘We swear you will not enter but over our dead bodies.’”

Opposition sources confirmed however, that armed clashes between the Syrian army and unknown militants were taking place, meaning the tanks were sent against armed militants, rather than protestors as Shadid suggested. Al-Jazeera quoted a Deraa resident on April 27, 2011 as noting that, “The army is fighting with some armed groups because there was heavy shooting from two sides…I cannot say who the other side is, but I can say now that it is so hard for civilians.”

Opposition activists Sally Masalmeh and Malek al-Jawabra also confirmed to Wall Street Journal reporter Sam Dagher that during the Syrian army’s assault on the al-Omari mosque in April 2011, opposition militants had barricaded themselves inside the mosque and were stockpiling weapons there. Masalmeh and Jawabra resorted to conspiracy theories to explain the presence of weapons in the mosque, however, suggesting that “there were people among the protestors working secretly with the Mukhabarat [Syrian intelligence] and that it was they who facilitated the procurement of weapons and urged confrontation with the army.”

These claims of conspiracy are not credible however, given additional admissions from other pro-opposition sources. For example, the activist from Deraa, Abd al-Qader al-Dhoun, was proud to acknowledge that two of his cousins fought and died in clashes with Syrian security forces at the al-Omari mosque during this period. He stressed to the interviewer that claims they were “terrorists” were false, but that they were indeed armed militants using Kalashnikovs and pump action shotguns.

To Arm a Resistance

Anwar al-Eshki, a former Saudi general, alluded to his government’s arming of militants in Deraa during this early period. In an interview with the BBC, al-Eshki explained that he had been in contact with opposition militants in Deraa, and that they were stockpiling weapons in the al-Omari mosque, apparently against the wishes of the mosque’s imam, Sheikh Siyasna. Al-Eshki then described the Saudi rationale for providing weapons to the militants, explaining that “To arm a ‘resistance’ doesn’t necessarily mean to give them tanks of heavy weapons like what happened in Libya. However, you give them weapons, so they can defend themselves and exhaust the army. The goal is to drive the government forces outside the cities to the villages.”

Foreign efforts to covertly spark an insurrection from Daraa, as described by al-Eskhi, are unsurprising, given the city’s location near the Jordanian border. CIA plans to spark an insurrection in Syria all the way back in 1957 recommended the same strategy. Historian Mathew Jones writes that the ”creation of an incident along the Syrian–Jordanian border was seen as the most promising scenario to spark outside military intervention. King Hussein’s [of Jordan] cooperation and influence could be enlisted to induce one or two of the Bedouin tribes residing in southern Syria to stage a rising of sufficient scale to provoke a Syrian army counter-attack…In addition, SIS [British intelligence] and CIA should gather Syrian opposition groups together in Jordan under the aegis of a ‘Free Syria Committee,’ while ‘Syrian political factions with paramilitary or other actionist capabilities should be prepared for execution of specific tasks suited to their talents.’”

Other pro-opposition sources detailed efforts to smuggle weapons to opposition militants inside the country during March 2011, which also contradicts conspiracy theories that the militants fighting in Deraa were secretly receiving weapons from the Syrian government to corrupt an otherwise peaceful protest movement.

Prominent opposition and human rights activist Haitham Manna’ provided evidence that elements close to pro-Saudi Lebanese politician Saad Hariri were funneling weapons to militants into Syria, including in Deraa. Muhammad Jamal Barout notes that Manna’ publicly disclosed in an interview on al-Jazeera on March 31, 2011, that “he had received offers to arm movements from Raqqa to Daraa three times by parties he did not identify in the interview.” Barout additionally writes that, according to Manna’, there were secret communications between some Syrian businessmen abroad who found themselves in a battle of revenge with the Syrian regime because their interests had been harmed by the network of the pro-regime businessman Rami Makhlouf, and that these groups were willing to fund and arm opposition movements throughout the country. Barout notes that these businessmen apparently had relations with professional networks capable of delivering weapons to any location in Syria and that some members of the Future Movement (a prominent political party in Lebanon led by Saad Hariri and known to have strong Saudi support) were among those arranging these weapons shipments.

Manna’ confirmed further details to journalist Alix Van Buren of Italy’s la Repubblica newspaper, speaking “about three groups having contacted him to provide money and weapons to the rebels in Syria. First, a Syrian businessman (the story reported by Al Jazeera); secondly, he was contacted by ‘several pro-American Syrian opposers’ to put it in his words. (he referred to more than one individual); thirdly, he mentioned approaches of the same kind by ‘Syrians in Lebanon who are loyal to a Lebanese party which is against Syria,’” presumably referring to the Future Movement in Lebanon as well.

Further confirmation of Hariri’s involvement in arming Salafist militants fighting the Syrian government later emerged from reporting by Lebanese journalist Radwan Murtada. In December 2012, Murtada reported that his newspaper, al-Akhbar, had obtained audio recordings of Future Movement parliament member Okab Sakr organizing weapons transfers to the armed Syrian opposition groups at the behest of Saad Hariri. Murtada’s reporting indicated further that Sakr was directing attacks against the Syrian army from operations rooms in both Lebanon and Turkey, and that he enjoyed close relations with intelligence officials from Qatar, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia.

Latakia

The early involvement of al-Qaeda was also evident in Latakia. On March 25 and 26, 2011 protests and violence also erupted in the northern coastal town, home to both Sunnis and Alawites. As elsewhere, conflicting reports emerged about the source of the violence. Human Rights Watch reported that “Anti-government demonstrators in Latakia who spoke to television outlets accused the security forces of opening fire on them, while officials and pro-government protesters accused the anti-government protesters of having guns and shooting at police.” Government sources claimed 12 were killed, including civilians, members of the security forces, and two unknown gunmen that allegedly opened fire from rooftops, and that the army was dispatched to the city in response to the violence.

On March 27, 2011 Al-Quds al-Arabi reported that an organized effort was in place to spread rumors that Alawites would be murdered by Sunnis, and Sunnis murdered by Alawites, and that the security services had arrested several foreigners, most likely Jordanians. The paper also reported that gunmen had been roaming through Latakia in cars, some carrying fake plates, while firing shots at homes and in the streets, leading to three deaths. This resulted in locals forming self-defense committees to prevent strangers from entering their neighborhoods.

The general government version of events was supported by the Indian ambassador, V.P. Haran, who as noted above, claimed that al-Qaeda militants had carried out attacks in Latakia on March 25.

On March 29, 2011 the Lebanese newspaper al-Safir detailed unconfirmed reports from an Arab diplomatic source claiming that Syrian authorities had confiscated seven boats loaded with weapons coming from the northern Lebanese coast, and that Syrian and Lebanese militants had entered Syrian territory through the Bekaa valley and some points in northern Lebanon. Further, these militants had allegedly carried out military operations, including sniping and shooting using night vision equipment and sniper rifles.

Time Magazine journalist Rania Abouzeid similarly reported al-Qaeda affiliate militants were active in Latakia province early in the crisis. She reports that a Salafist militant “enlisted a small group of Salafi friends from Latakia who, along with a few local men he’d armed, overran half a dozen small police stations in villages dotted around the city. The first raid was in mid-April…Mohammad said he netted nine Kalashinikovs and ammunition. It wasn’t hard.” Muhammad had previously recruited fighters to go to Iraq to fight with al-Qaeda in Iraq in 2003 and went on to become a commander in al-Qaeda’s official Syrian wing, Jabhat al-Nusra, or the Nusra Front.

Banias

The role of U/S. and Saudi planners to topple the Syrian government was also evident during the early weeks of the crisis in the coastal town of Banias, where the government also deployed tanks, not to suppress protests but to respond to opposition attacks on Syrian soldiers and to prevent a sectarian war erupting between Alawite and Sunni residents. In this case, the agent working on behalf of U.S. and Saudi interests was former Syrian Prime Minister Abdul Halim Khaddam. As discussed above, he defected from the Syrian government in 2005, and began working toward regime change at that time with both the Muslim Brotherhood and neoconservatives from the Bush administration.

According to researcher Sabr Darwish of the EU-funded and pro-opposition Syria Untold, protests in Banias began on March 18, 2011 as well, and were organized and led by Anas Ayrout, a local Sunni cleric and Imam of the al-Rahman mosque, with activist Anas al-Shaghri also playing a prominent role. Ayrout later became a member of the Western-backed Syrian National Council (SNC) and in 2013 called for killing Alawite civilians to create a “balance of terror” to compel them to abandon support for the government.

The demands of the protesters in Banias included some of a conservative Islamic nature, rather than for democracy. According to opposition activist Bissam Walid, these demands included the release of a detainee, Ahmed Hudhayfa, who had been arrested in Damascus, returning veil wearing female teachers who had been transferred to jobs in other ministries to their teaching positions, the lowering of electricity prices, and the separation of boys and girls in schools.

During the first protest, demonstrators attacked an Alawite truck driver before Anas Ayrout intervened to stop them. According to Sabr Darwish, protests in Banias were otherwise peaceful and allowed to go forward unsuppressed by government officials over the following three weeks, while government officials were responsive to protestors demands. During protests on April 1, 2011 demonstrators chanted slogans against Iran and Hezbollah, criticizing their alleged intervention in Syria. The next week, demonstrators began a sit-in in the center square of the city.

If They Shoot At You

Events in Banias became violent on Saturday April 9, 2011 when 9 Syrian soldiers were killed while traveling by military bus in Banias. Regarding the attack, the Guardian reported that, “Syrian soldiers have been shot by security forces after refusing to fire on protesters, witnesses said, as a crackdown on anti-government demonstrations intensified. Witnesses told al-Jazeera and the BBC that some soldiers had refused to shoot after the army moved into Banias in the wake of intense protests on Friday.” The Guardian also linked to footage on YouTube that it claimed, “shows an injured soldier saying he was shot in the back by security forces.”

Prominent Syria expert and academic Joshua Landis quickly showed claims made by the Guardian and Wissam Tarif to be false. Landis showed that the soldiers were instead killed by opposition militants using sniper rifles from a distance as the soldiers’ bus was entering the town. Landis writes that, “Video of one soldier purportedly confessing to being shot in the back by security forces and linked to by the Guardian has been completely misconstrued. The Guardian irresponsibly repeats a false interpretation of the video provided by an informant…The video does not ‘support’ the story that the Guardian says it does. The soldier denies that he was ordered to fire on people. Instead, he says he was on his way to Banyas to enforce security. He does not say that he was shot at by government agents or soldiers. In fact, he denies it. The interviewer tries to put words in his mouth, but the soldier clearly denies the story that the interviewer is trying to make him confess to. In the video, the wounded soldier is surrounded by people who are trying to get him to say that he was shot by a military officer. The soldier says clearly, ‘They [our superiors] told us, “Shoot at them IF they shoot at you.”’”

Landis notes further that the “interviewer tried to get the wounded soldier to say that he had refused orders to shoot at the people when he asked : ‘When you did not shoot at us what happened?’ But the soldier doesn’t understand the question because he has just said that he was not given orders to shoot at the people. The soldier replies, ‘Nothing, the shooting started from all directions.’ The interviewer repeats his question in another way by asking, ‘Why were you shooting at us, we are Muslims?’ The soldier answers him, ‘I am Muslim too.’ The interviewer asks, ‘So why were you going to shoot at us?’ The soldier replies, ‘We did not shoot at people. They shot at us at the bridge.’”

Azmi Bishara, a well-known al-Jazeera analyst and the general director of the Qatar-based Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, later confirmed that opposition militants killed the soldiers as well. Bishara cites a political activist from the “Together” movement in Banias as explaining that opposition militants fired on the soldiers from an observation bridge on the international highway opposite the city which links Latakia and Damascus. Bishara links the attack on the military convoy to “the ongoing arms smuggling operation across the Lebanese border,” which was used to smuggle weapons into both Homs and Banias. Bishara writes that “Muhammad Ali al-Biyassi, (one of the people working with [former Syrian Vice President] Abd al-Halim Khaddam) requested arming the people which went out in protests in the beginning of April 2011. And this person led the operation to send weapons to Banias. And the operations to smuggle weapons led to military confrontations with the Syrian army and security forces.” Bishara cites as his source “a person from the family of al-Biyassi who witnessed these operations and who soon was among those who carried weapons and told the witness the details of the operations.”

The Decision