Why is the upcoming referendum so important?

It is important both because of its content as well as for the symbolic meaning it has assumed. The strokes of the counter reform against the constitution fall very hard. The newly conceived Senate (Upper House), for instance, retains important powers (such as on constitutional questions, in the relations with the EU, about local authorities, the election of the president, etc.), but should no longer be elected. The Senate was thus not abolished, as Renzi’s propaganda pretends, but it was democracy has been abolished. But the most important point of the counter reform is the election law (“Italicum”) which allows, through the ballot mechanisms, to obtain with just 40% of votes, 55% of the seats. It’s a law conceived by and in favour of the Democratic Party (PD). If it is passed, it will lead to a de facto presidentialism. A part for all its specific contents, the referendum has been charged with a more general political meaning: it is a vote on Renzi and Renzism. In this sense it represents a new round in the revolt of the under classes against the elites with a clear class content. And it is no coincidence that the polls predict a majority of NO in the Centre and the South (where poverty and unemployment are widespread), while in the North-West the YES appears to be in advantage.

Which forces build the NO camp?

Among the parties, the Five Star Movement (M5S), the forces of the rightist Lega Nord, Forza Italia and Fratelli d’Italia and of the leftist Sinistra Italiana, Rifondazione Comunista and almost all smaller forces have declared to be for the NO. If we can assume that the electorate of the left, the M5S and of the Lega will almost all be for the No, this is different for Forza Italia. Its electorate, estimated around 10%, is deeply divided. Berlusconi’s TV channels behave aseptically, while the leader does not express himself. Socially the No front is even wider. Hundreds of local committees have been founded, mostly independently from the political parties. Their activities enjoy a significant participation and resonance.

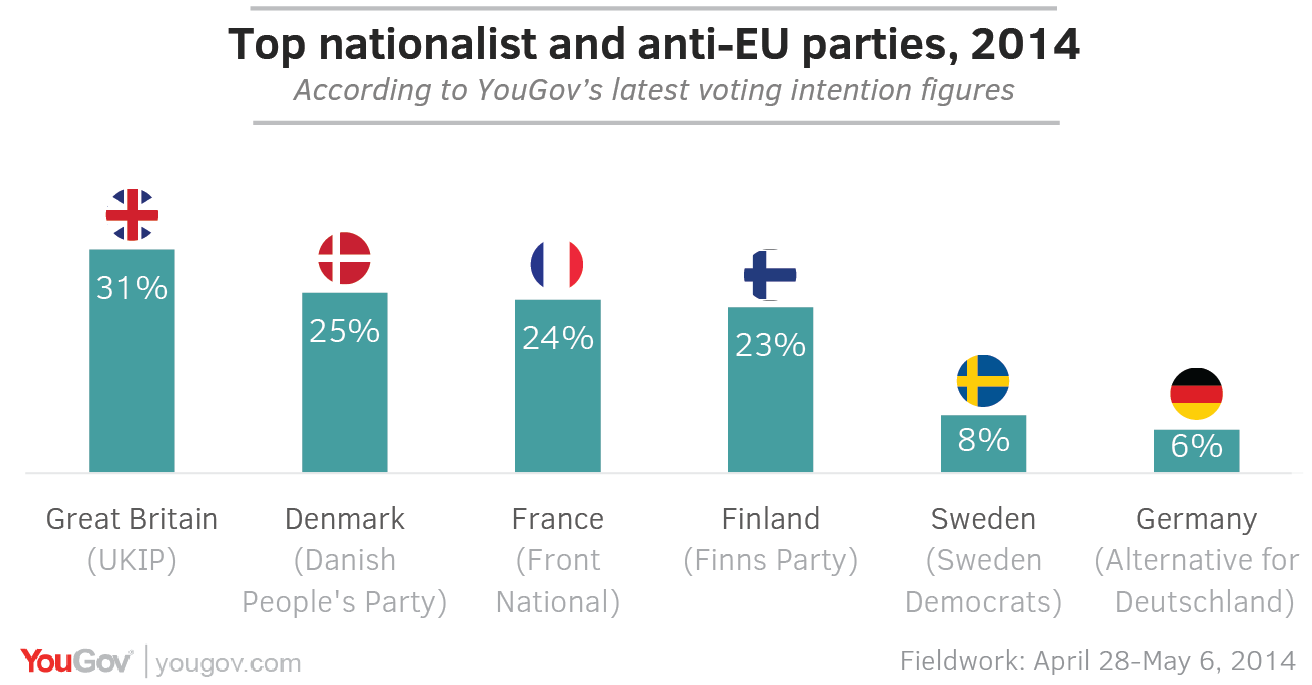

How do you explain the turn of the Lega Nord, which propagated Padania (North of Italy) as part of one region with Bavaria in contraposition to Italy, whereas today it stands against the Euro and for the independence of Italy?

The new leadership of the Lega Nord, represented by Matteo Salvini, grew into the vacuum created by the crisis of Berlusconism. The idea behind this was, on the one hand, to break the narrow geographical boundaries defined by Padania, and, on the other hand, to break the political boundaries set by Berlusconi’s alliance of the right. The goal seems to be a party modelled on the Front National of Marine Le Pen. This serves two main topics: No to the Euro, but above all No to immigration, with increasingly accentuated xenophobia. According to current opinion polls, the Lega could increase with this line its voting share from 5-6% to 12%. Yet the results of local elections in June were not good for Salvini’s Lega and the expansion to the South seems to be doomed to fail.

Are the anti-Renzi forces accused to build a cross-front, as it happened in England and as it often happens in other countries?

The Renzi camp tries first of all to discredit all opponents as the “front of the old”. The accusation of a red-brown front does not hold for two reasons: first, it is normal that in a referendum ideologically very different forces can converge. Secondly, in this case, it is the right that is forced to adopt legal-political arguments typical of the left. It has therefore to speak about things like democracy, representation, balance of forces, etc.

How do you interpret Bersani’s “no”? Is it merely a tactical attempt to obtain concessions now that his party enemy [Bersani was former secretary of the Democratic Party and has been disempowered by Renzi] is in trouble and depends on political help?

Bersani’s position is related to the PD internal struggle. Renzi is like a steam roller and his slogan “scrapping (rottamazione) the old” is perceived by the party minority led by Bersani as a real threat. Even if this current has been holding up since three years, none of its member, with the exception of the deputies Stefano Fassina and Alfredo D’Attorre, was ready to leave the party. In no fewer than six parliamentary votes, they have succumbed to party discipline and given their consent to the constitutional reform. Now they are threatening Renzi with a no, because they could not even obtain a slight modification of the electoral law. It is clear that they have a very weak position. I do not believe that with their position they want concessions now. Rather, they prepare for the situation after the 4th of December. Should the NO win, they will try to get the party back under their control. No easy thing, but to a certain extent it could work. If the YES prevails, then a part of them will be forced to leave the party. But we should talk about this later.

As far as the economic elites are concerned, do they still compactly support the Euro, as in Spain or Greece, or does their block already show some cracks?

The elites are still compact, but we already can observe some cracks in the structure. It is obvious that Italy’s significance is not only bigger than Greece’s, but also than Spain’s. Therefore, the idea is that some concessions may be granted from Brussels. This fits with the policy of Renzi’s government, which calls again and again for more “flexibility”. As soon as this line fails, there will also be a break in the ruling block. The hottest topic, though, is the crisis of the banks. There could be a decisive conflict about the rescue measures to be adopted.

What is the role of the banking crisis and what solution does Renzi offer?

The crisis in the Italian banking system is striking. It is a direct result of eight years of recession. Even today, GDP is 8% below that of 2007. There are too many families and companies that are no longer able to pay back their loans. The banks urgently need recapitalization to cover their losses. But no private investor is willing to throw his money into a barrel without ground. Therefore, the only remaining possibility is a rescue by state. However, as early as 2012, the government refused such an intervention (as it was carried out in Spain), referring to the already very high debt of the public sector. But now everything comes to light: the promised recovery does not want to come. Economic growth remains below 1%. And the rules of the banking union, in particular the obligation for creditors to bear some of the burden (bail-in), put the banks in an untenable situation. Until now, the Renzi government tried to fix these problems from case to case. Either a partial bail-in was carried out as in the case of four banks in Central Italy where many savers have already been forced to pay (some of them, often very simple people, losing all their savings). Or recapitalization through private capital, but where the public hand provides the back-up in the background, as it happened with two Venetian banks. (There, the shareholders were wiped out.) Now there is the still larger case of Monte dei Paschi di Siena. Here, the government decided to approve a deal favouring JP Morgan and thus revealing its connection to the US financial world. Even the Corriere della Sera, usually very friendly to the government, attacked it violently. Meanwhile Renzi insistently repeats that the markets eventually will sort out these problems. In fact, the situation is explosive. According to many economists, a new crisis in the financial markets could have a dramatic effect on the Italian banking system. Either there is a series of bail-ins, as Lars Feld demands, or the banking union is breaking down. At this point, there will most likely be a break also within the ruling block.

How does Renzi defend himself? Does he still have a chance at all on December 4?

Just over a year ago, Renzi was thought to win with an overwhelming majority. Then it became clearer that he had to increasingly face difficulties. Today the opinion researchers attest the No to be slightly ahead, but not more than a few percentage points. Not enough to be sure about the result. In my opinion the NO is stronger than it is generally said to be. At the same time, Renzi’s catch-up cannot be excluded. Both the cards of fear and of Euroscepticism, which is somewhat more insidious, will be played. Some also believe in a surprise, namely an open support in favour of YES by Berlusconi. Renzi can anyway count on the one-sidedness of the media, as well as the advantage of having all the levers of government power available, beginning with some promises made in connection with the next budgetary law. In summary: Renzi is at a disadvantage, but retains the opportunity to catch up. The NO-forces must therefore strengthen their efforts in the next weeks.

Renzi calls Brussels and Berlin for a softening of austerity, and obtained some support from France and Austria. Is there a real chance of a light version of Tsipras?

It seems to me that Renzi’s line is reaching its limits. In a country like Italy, a policy based on few decimals, cannot produce sufficient results. Such a moderate mitigation of austerity cannot stop the trend towards stagnation. At the same time, even such a policy clashes against EU rules and in particular against the Fiscal Pact. It is difficult to foresee how long this situation can carry on. If Renzi should remain in power, he will try to obtain concessions by every further delicate passage in the European political life such as the French presidential elections. In any case, I think it is more likely that the banking issue leads to an open clash with the EU Commission and with Berlin than the conflict about austerity.

What could happen in the case of a victory of No?

It is clear, for me, that Renzi cannot remain prime minister. That would wear out too much his image as an innovator. He is too intelligent to make such a mistake. However, he could remain as chairman of the PD, but this could lead to internal convulsions in the party. The Plan B of the ruling bloc is certainly a grand coalition (larghe intese), to be built either through a temporary institutional government or also by new elections. This could be carried out under the leadership of the President of the State by means of a transitional government that would change the electoral law and hold early elections in 2018. It is difficult to say who could lead this government (many think of Enrico Letta). In any case, Forza Italia would like to be part of the game. In general, and that is for us of greater interests, out of this situation a period of crisis of the ruling bloc and a revival of opposition forces would result. In order to understand the difficulties of the elite, one must keep in mind that Renzi has been accurately chosen and helped to take the government by the most important centres of economic power. From their standpoint, Renzi represents the right mix of liberalism and populism, of privatization politics and rhetoric against austerity. A rehash with the right person will not be easy. With regard to the forces that stand for a break with the Euro and the EU – in a democratic perspective and in defence of the interests of the broader population – the moment could have come for them to make a qualitative step forward. It will not be easy, but certainly easier than after a victory of YES. The development of the M5S is crucial in this respect.

What are the scenarios? Is the Five Stars Movement able to lead the country? If you take Rome as an example, where they have recently succeeded to conquer the position of the mayor, it does not look like this.

The M5S cannot expect being able to form a government alone. They are very clear for a “no” vote at the referendum, as well as against Renzi’s election law, although some of their top representatives think they could benefit from the ballot mechanism. I do not believe that Di Maio [the M5S elected deputy holding, as vice president of the Deputy Chamber, the most senior position of his party in Parliament] will have any chance to become Prime Minister. For a simple reason: considering their systematic rejection of any alliance, the M5S could only win with the Italicum (the electoral law which grants additional seats to the most powerful party excluding coalitions). But if the NO wins, the Italicum would be rejected. On the contrary, if the majority votes YES, Renzi would probably call for new elections in spring 2017, hoping to use the positive wave of the victory by the referendum also for the general elections. Moreover, the social basis of the Cinque Stelle is not sufficient to allow them to govern alone, since their social rooting is much weaker than their election successes suggest. See the difficulties they are facing in Rome. At the same time it would be an error to think that Rome alone would lead to the decline of the M5S in a mechanical and immediate way. A victory of NO would mean a turning point for M5S and its electoral strategy. There are two basic problems for them: they will have to overcome the myth of the web and to seriously deepen their roots in the society to forge the broadest possible alliance of political and social forces. Of course, such an opening would also bring about another change, a restructuring of the movement, which cannot progress without a statute, territorial organizations and a democratic party life.

What are the forces of the left doing?

In the present Parliament there is only one formation that associates itself with the left: Sinistra Italiana. This was the result of the enlargement of Sinistra Ecologia e Libertà (SEL) with some deputies leaving the PD. However, there was also the opposite movement. Some of SEL deputies left and joined the PD. In any case, nothing new is to be expected from this corner. Because of internal fractures, they may not even be able to hold their party congress. On the one side, there are Fassina and D’Attorre, coming from the PD, who have a very critical position about the Euro and, on the other side, those who wish to progress towards the United States of Europe. Not to mention also a sort of atavistic transformism of these leftists, which brought the bulk of SEL into the PD, would the PD manage to get rid of Renzi. The second essential remaining force of the left is Rifondazione Comunista. It still has a large number of activists, but it is totally unable to renew itself. In their positon towards the EU, there was even a step backwards: since the withdrawal from the Euro has been demanded by forces of the right, this request has been declared rightist per se. This shows their inability to understand the current reality, not to mention their passivity in this respect. Fortunately, there is also another left which has gained weight in recent years. I am thinking of the groups that have joined the Eurostop platform: Unione Sindacale di Base, Programma 101, Partito Comunista Italiano (formerly PdCI), Rete dei Comunisti (Network of Communists) and an anti-Euro minority within Rifondazione, as well as a considerable number of intellectuals. Although there are differences between them, they converge in putting at the centre the struggle against the Euro and the EU and trying to connect the social with the national question, just as the communists have done in different contexts.

Can you explain the perspectives of the Eurostop coalition and of your own organization P101?

Program 101 (P101) is still a project and was born as development of the Coordinamento della sinistra contro l’euro (Left Coordination against the Euro). We are also working on a further coalition on federal basis, which on its turn wants to be one of the subjects of a broader democratic and social front, which offers itself for the leadership of the country. The Eurostop coalition consists of several components that have joined to carry out common initiatives such as the No-Renzi Day with a demonstration in Rome on 22 October. The importance of P101 lies in its capacity to act as a driving force due to its analyses and proposals. I see its strength in our ability to think big and openly, conscious of the historical changes awaiting us. This is perhaps what sets us apart from the traditional left. While they have been stuck in a sterile, almost cosmic pessimism, we believe that our society is demanding a new policy, which is now served by the M5S – and tomorrow who knows by whom. While they do not consider how traumatic the consequences of the crisis have been for the lower classes, we are convinced that there will be tremendous shifts. New spaces are opening up. There will be violent struggles, the outcome of which is by no means predetermined, but in which we shall be engaged with our ideas.

translation: Tiziana Fresu