A growing number of organizations in Europe is demanding a complete overhaul of regional pharma policies in order to protect people’s health over profits

February 10, 2024

“It’s time to step up, promote health justice, and meet the real needs of people,” says Alan Silva from the European chapter of the People’s Health Movement (PHM), addressing the need for revolutionizing pharma policies in Europe. A long-time advocate for access to medicines, Silva understands how important it is for Europe to change the way it thinks about research and development, but also production and distribution of health technologies.

If the region were able to de-link itself from the interests of transnational pharmaceutical companies, it would be a true game changer, he says. “We need public pharma in Europe so we can stop relying on health solutions driven by profit,” he says.

Inspired by a different vision for Europe’s pharmaceutical sector, a coalition of right to health organizations and health experts launched a call for building a network of public research and development institutes that would ensure profiteering on people’s health by Big Pharma companies finally comes to a stop. The coalition, which includes PHM Europe, Medics for the People (Médecine pour le Peuple, MPLP), Health Action International (HAI), and a host of other groups, is preparing for a first conference on the topic, to be held mid-March.

Such a public network would ensure that new drugs are researched through public channels and – crucially – remain in public hands in the later phases of their development. In this scenario, all the knowledge accumulated in research and development would be shared through a public database. No patents would be registered: private companies might still be able to participate in the production of drugs, but they would be prevented from monopolizing public knowledge.

This would have an important impact on the availability of treatments and on the price of certain medicines, says Jaume Vidal from HAI. “It would really be a boost for public research and development capabilities, in the sense that for the first time we would have something like state-owned facilities.”

According to Tim Joye from MPLP, Europe needs this kind of re-framing urgently. Right now, European Union policies are too reliant on the private sector, which is leading to rising prices for medicines and essential products. This is straining public budgets, notably those foreseen for health and social security, draining precious resources that could otherwise be used for employing more health workers and improving their working conditions.

In fact, EU members’ public spending on drugs continues to skyrocket. In less than 10 years, between 2000 and 2009, this segment of the public budget increased by 76%, warned the European Network Against Privatization of Health and Social Services, the European Public Services Union (EPSU), and PHM Europe as they announced a campaign pushing for better, people-centered policies ahead of this year’s EU election.

If this were to change, and the influence of Big Pharma over drug prices reduced, estimates say that savings across the EU would amount to as much as EUR 140 billion: money that could be invested in strengthening public health systems, training more nurses and pharmacists, and fulfilling the promises given to health workers at the height of COVID-19.

Granted, the building of such a network would cost money and time, but it’s far from unachievable. All combined, investments would not be that different from those made into current health innovations – but they would benefit a wider group of people. And they could be kick-started by the savings made on drug expenses.

“The only way to make public pharma happen in Europe is to build the broadest movement possible and keep pushing for it day in and day out. It’s, of course, a long-term commitment. But let’s face it, we can’t sit around waiting for governments, private companies and multilateral institutions to spontaneously hand us what we need,” says Silva.

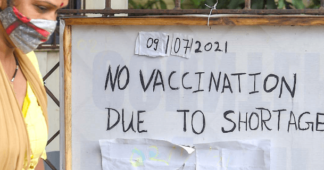

While trade unions and civil society in Europe want to see radical changes following the fiascos experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, most policymakers at the EU level do not share their sentiments. During discussions on union-wide pharmaceutical directives, the best that could be heard was a proposal to shorten the period when pharmaceutical companies enjoy unimpeded access to new drug markets.

Even mild announcements like these were countered by regional associations of pharmaceutical producers, who implied that attempts to weaken the existing intellectual property framework would result in fewer drugs being developed, jeopardizing health in Europe.

What Big Pharma failed to disclose in their statements was that the current system benefits their shareholders over public health interests. Among other things, pharmaceutical companies are able to cherry-pick the drugs they want to research, leading to health conditions deemed as not profitable enough – antimicrobial resistance, for example – being ignored.

Re-framing the system would bring new rules. “We could decide ourselves in a democratic way, in which studies, in which trials, in which development we want to invest,” said Joye.

The attempt to build public pharma infrastructure across Europe is, according to Jaume Vidal, “an attempt to do things better.”

“It’s a necessity to bring research and development facilities closer to health needs, to bring health needs closer to access.”

Changing Europe’s approach to pharmaceutical research and development would also mean the region standing in solidarity with the rest of the world. Since the very beginning of the pandemic, many countries from the Global South have fought for a fairer system that would enable everyone to access essential medicines and technologies, irrespective of their income status. Throughout this time, European representatives and institutions have instead advocated for the interests of Big Pharma.

If alliances were to change under the pressure of people’s movements, it would allow Europe to make at least partial amendments for the approach taken during COVID-19. “It’s a global thing. Health is not a product and everyone should get the best technology that human knowledge can produce,” says Alan Silva.

For more information about the Public Pharma for Europe conference, click here.

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.