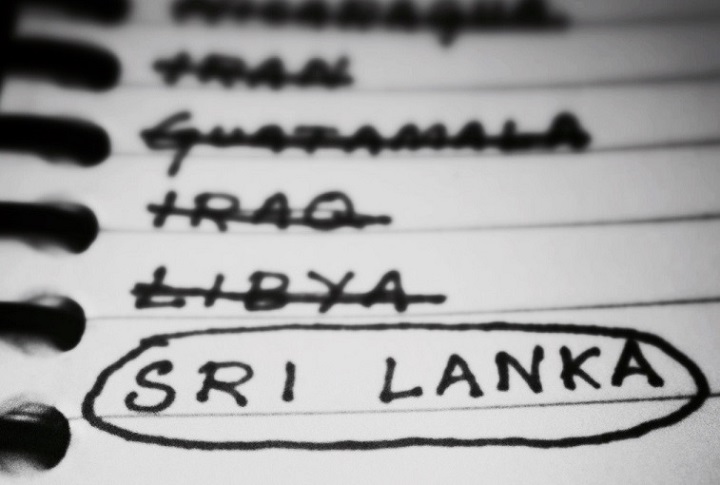

By Lasanda Kurukulasuriya

The commencement of duties by Sri Lanka’s new Navy Commander Vice Admiral Travis Sinniah merits special attention on account of some observations he made besides the pleasantries associated with assuming office. One of the statements at his first press conference in Colombo was regarding the future role of the Sri Lanka Navy (SLN) which he reportedly said would be “to protect commercial trade between the Gulf of Aden and the Straits of Malacca.” According to reports he was referring to the role of sea marshals in protecting commercial vessels from pirates.

Obviously the Navy Commander was not expressing a personal decision or opinion but reflecting the position of his government. He was in fact echoing a view articulated earlier by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe when he addressed naval personnel at a commissioning ceremony in Trincomalee in April last year. The PM said the SLN would have to prepare for a role where it would be called upon to protect not only Sri Lanka’s territorial waters but also the seas of the entire Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean as well – “from the Maldives to the Strait of Malacca.” The PM went so far as to say Sri Lanka should arm itself with more ships, planes and weapons for this purpose.

It would be relevant to ask if the GoSL has thought through the implications for Sri Lanka of asserting this ambitious new role, in a context where the rivalry among big powers in the region is intensifying, and security concerns growing increasingly complex. Sri Lanka would be projecting itself into a strategically sensitive triangular relationship currently playing out among India, China and the US in the Indian Ocean Region. India’s suspicions of China’s motives have grown, with China’s increasing maritime presence and especially with its new ‘Belt and Road’ initiative. The stand off in the Doklam plateau is a pointer to long simmering tensions between the two Asian giants – both nuclear powers – despite the major trade relationship between them.

The US and Indian naval strength in the Indian Ocean is said to be far greater than that of China. Ironically, both India and China seem to fear ‘encirclement,’ going by what analysts on both sides have been saying. Americans came up with the concept of a ‘String of Pearls’ consisting of a series of strategically located ports developed by China such as those in Mynmar, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan which, according to the theory, encircles India and could be used for military purposes. Chinese analysts too express fears of encirclement, in the context of beefed up military facilities in India’s Andaman and Nicobar islands located near the Strait of Malacca.

Almost 40% of China’s foreign trade depends on Indian Ocean sea lanes. With over 80% of its imported oil going through the Strait of Malacca, China has long feared the possibility of rivals blocking off access to this vital channel. Adding to these fears is the US military build-up in the Asia Pacific region leading to escalating tensions in the South China Sea. Several analysts have worried about the increasing risk of a Third World War on account of the US having encircled China with nuclear weapons.

Chinese analysts assert that China’s purpose in maritime expansion is commercial and not military. Hence the appearance of what China calls a ‘logistical facility’ in Djibouti – seen as its first foreign military base – has become the subject of much talk. These discussions may not mention that Japan, France and the US too have bases there. For perspective, compared to China’s one, the US has some 800 bases in foreign countries, according to David Vine writing in 2015 in The Nation. (That figure may have increased by now.) “… The United States likely has more bases in foreign lands than any other people, nation, or empire in history” says Vine.

“U.S. and Indian experts are debating whether China is pursuing a strategy of building commercial port facilities along the rim of the Indian Ocean that will one day be used for military purposes” writes David Shinn in a recent paper on ‘China’s Power Projection.’ Shinn who is an adjunct professor in the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University notes that “While China is expanding its naval capacity in the Western Indian Ocean, it is important to understand that the PLAN’s (People’s Liberation Army Navy’s) highest priorities remain along China’s coast, the South China Sea, Strait of Malacca, and Western Pacific.”

China’s build-up of military installations on islands of the South China Sea would need to be seen against the backdrop of these concerns over access. A dispute has arisen for example with the Philippines, over airstrips being built by China on the Spratly Islands. According to Indian Defence News, this was ‘a dispute without priority’ until Washington pressured Manila, and the Pentagon launched a propaganda campaign called ‘freedom of navigation.’

“What does this really mean? It means freedom for American warships to patrol and dominate the coastal waters of China. Try to imagine the American reaction if Chinese warships did the same off the coast of California” the article argues. “Why is China building airstrips in the South China Sea? The answer ought to be glaringly obvious. The United States is encircling China with a network of bases, with ballistic missiles, battle groups, nuclear-armed bombers,” the report says.

In a scenario so fraught with tension, one needs to ask on what basis Sri Lanka is rushing in to “protect the oceans from the Gulf of Aden to Strait of Malacca.” Besides, the piracy threat in Gulf of Aden is said to be greatly reduced now as a result of coordinated international efforts. With the exception of an incident in March this year where Somali pirates hijacked a ship, the last recorded hijacking incident is reported to have been in 2012.

Sri Lanka’s Navy, while it has distinguished itself remarkably in a war that liberated the country from terrorism, does not pretend to be on par with the navies of the world’s nuclear powers. As such, if it takes part in any international exercise of patrolling the high seas it would have to be as a junior partner of a bigger naval force. In the event of a major conflict, the geopolitics of the situation would demand that Sri Lanka take sides. And that will be the end of Sri Lanka’s professed status of being ‘friends with all and enemies of none.’ With this ill-considered bid to curry favour with the US by offering to ‘protect the sea lanes from the Gulf of Aden to the Strait of Malacca,’ will Sri Lanka end up between the devil and the deep blue sea?