The third in a seven-part, multi-week series of commentary on the COVID-19 crisis

This is the third in a seven-part, multi-week series of commentary on the COVID-19 crisis entitled WHAT IS TO BE DONE? A MANIFESTO FOR POLITICS AMID THE PANDEMIC AND BEYOND by Radhika Desai, Professor of Political Studies and Director of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group at the University of Manitoba.

Great political hope has been aroused by the breakdown of neoliberal economies and their politics in core capitalist countries. Staunch neoliberal governments have been forced into spectacular policy U-turns such as income support packages of unprecedented size. Strikes and other actions are breaking out, while unions are demanding a greater role in how lockdowns and their easing are implemented. Intellectuals are competing to propose radical new ideas, from a universal basic income to deeply negative interest rates to resurrecting anti-trust legislation to breaking up large monopoly corporations. Even European governments are proposing non-repayable bonds to deal with the debt crisis and organs of the capitalist press are demanding a reversal of neoliberalism unbelievable only two months ago:

Radical reforms—reversing the prevailing policy direction of the last four decades—will need to be put on the table. Governments will have to accept a more active role in the economy. They must see public services as investments rather than liabilities, and look for ways to make labour markets less insecure. Redistribution will again be on the agenda; the privileges of the elderly and wealthy in question. Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix.

However, this political hope must be realised, if at all, in complex conjuncture and against the odds posed by the long-term weakening of left forces.

It is true, as we shall discuss in the next installment, that the neoliberal ruling classes face a scissor: a widening gap between their governmental and political abilities and the public health challenge. It has turned what should have been only a public health crisis, albeit a serious one, into an unprecedented economic collapse, both in degree and character, and a fundamental, constitutional crisis of neoliberal capitalism.

However, the left faces an historic disparity between its own long-depleted abilities and the hopes it has begun nursing that is even wider. Its abilities—levels of union organization and votes for left-of-centre parties, to take only two of the more obvious indicators—have taken a beating amid the neoliberal assault of the past four decades. Moreover, if one takes a longer historical view, its debility appears even more serious.

The Western Left in World Revolution to Date

Perhaps the most fundamental thing to recall is that there has never been a successful revolution in Western societies. This is despite the fact that the Second International, the international federation of European parties of social democracy then marching under the banner of Marxism, expected that revolution would first occur there, in the homelands of capitalism. This expectation was belied. The first revolution against capitalism and imperialism occurred in Russia. Worse, the evolution of social democracy over the past century and a half since it appeared on the historical stage in the homelands of imperialism has consisted of progressive moves to the right both in terms of domestic and international policy.

Already before the First World War, despite the revolutionary and internationalist views of its leadership, the Second International was racked by debates over revisionism. It was essentially a dialogue of the deaf between those who emphasised the centrality of immediate reforms and concessions from the national state to the strength of the left and the longer-term goal of revolution, always conceived in abstract internationalist terms and overlooking the simple fact that by that time, workers had “a good deal more to lose than their chains”. Revolutionary internationalism went, moreover, hand in hand with imperialist attitudes of many in the parties of the Second International:

European socialists noticed the question of democracy in the colonial world only very exceptionally before 1914: not only were non-Western voices and peoples of color entirely absent from the counsels of the Second International, but its parties also failed to condemn colonial policy and even positively endorsed it. Socialists commonly affirmed the progressive value of the ‘civilizing mission’ for the underdeveloped world, while accepting the material benefits of jobs, cheaper good and guaranteed markets colonialism brought at home.

Lenin was the major exception. His famous pamphlet on imperialism, like that of his other Marxist comrades, may have been chiefly concerned with inter-imperialist rivalry which was likely to cause war and cost working class lives in Europe. Even Rosa Luxemburg referred to the colonial world and its ‘natural economy’ only to point out that its imminent absorption spelled the end of capitalism.

However, Lenin understood the centrality of colonial and semi-colonial domination and national liberation to world revolution. He had welcomed Japan’s victory over Russia and nationalist ferment in Persia and Turkey in 1905 and the European workers’ ‘Asian comrades’ in 1908. By 1916 he had anticipated the idea of the Three Worlds: with the First World War strengthening anti-colonial nationalism, he assigned socialists distinct tasks in the three types of countries. In the imperial countries they had to fight both capitalism and imperialism. In those that were neither imperial nor colonised, such as Russia, they had to work toward national ‘bourgeois-democratic reformation’ and link imperial and colonial working class struggles. Finally, in the colonial and semi-colonial countries, they had to champion national liberation alongside revolutionary bourgeois forces.

However, the further splits in European social democracy after the Russian Revolution ensured that it was the Third International and actually existing communisms that inherited and developed this understanding, connecting socialism and national liberation, the working class and the peasantry, capitalism and imperialism, not Western social democracy.

After the upheavals of the Thirty Years Crisis of 1914-45, including the dissolution of the Second International on the eve of the First World War, splits among left forces appeared everywhere: over the Russian Revolution after 1917, the failure of the German November Revolution, the Italian Biennio Rosso and other such uprisings in the wake of the First World War, the Great Depression and the successes of fascism. Moreover, the postwar period witnessed European social democracy jettison Marxism.

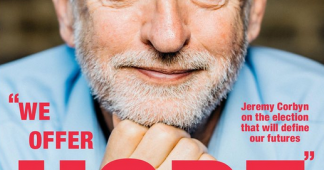

By the time the twentieth century closed, any commitment to socialism was also abandoned. Social democratic redistribution, itself reliant on such growth as capitalism could furnish, formed its political horizon. Left elements that continued to speak of planning, nationalisation and industrial policy, were anathema to the mainstream, including parts of the trade union movement. Even contemporary figures like Tony Benn or Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom have been regularly sabotaged by the weightier social democratic right.

While there are many studies of the denouement, two aspects of the intellectual history of social democracy, one related to its personnel and the other to its ideas, are rarely discussed and worth highlighting.

Brains and Numbers

Marx and Engels remarked in The Communist Manifesto that “entire sections of the ruling class are, by the advance of industry, precipitated into the proletariat, or are at least threatened in their conditions of existence. These also supply the proletariat with fresh elements of enlightenment and progress.” Certainly, intellectuals, themselves neither numerous nor working class but members of what, for want of a better description, we may term the professional managerial class (PMC), has played a major role in social democracy. The Fabians, in their quaintly blunt way, called this the alliance of “brains and numbers”. This class alliance was never easy and the danger of revisionism—the de-radicalization of the movement, its understanding and goals—always lurked. In the post-war period, it was realised. As the weight of the PMC current in social democracy grew, it led social democracy away from Marxism and further down the path to compromise with capitalism.

However, in the early post-war decades, the goal of socialism remained. It was not repudiated. That had to await late twentieth century developments that transformed the political orientation of the PMC. The historically left-ward bent of intellectuals was usually put down, by the right as well as the left, to the general overproduction of intellectuals. Lacking a place in the existing order of things, they joined forces opposed to it.

This pattern of intellectual life was decisively reversed by the end of the twentieth century. While the post-war expansion of education swelled the ranks of the PMC, they were also quickly absorbed into the wide and deep structures of monopoly capital and the expanded post-war state, now employing vast numbers of the credentialed in its welfare, health and educational structures, a new pattern of PMC political involvement emerged. Whereas, earlier they tended to side with liberal and left currents (John Stuart Mill had called the Conservative party of his time the ‘stupid party’), the vast expansion of education in the postwar period bifurcated intellectual life: “The main line of cleavage….ran between those employed by the private or profit-oriented sector and the public sector, including the non-profit-making institutions such as universities, churches and charitable foundations.” The former gave their political loyalties to parties of the right and the latter to those of the left.

Among parties of the right, the ascendancy of this new sociological stratum over the old grandees of conservative politics was marked. In the case of the UK, for instance, professionals like Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher succeeded grandees like the 14th Earl of Home, Alec Douglas-Home, in its leadership. Working through the various corporate funded think tanks and media, this new professional class engineered the shift of parties away from conservatism, with its vestiges of noblesse, and towards a harder politics of private property and individualism that neoliberalism represented.

The Emergence of Social Democratic Neoliberalism…

For a while their counterparts on the left, having participated in the student and youth revolts of the late 1960s, appeared set to take social democracy farther to the left, in a mirror image of developments on the right. However, though many of that generation remained true to the left wing values they expressed in their youth, looking back as early as the turn of the century, a very different reality was visible. As the boomer generation moved into positions of responsibility and power in the private, public and voluntary sectors, rather then polarising the political spectrum, they moved it, in its entirety, to the right. In country after Western country, the new social democracy of the Blairs, Schroeders and Clintons was the work of the generation of 1968.

The result was social democratic accommodation with the neoliberal settlement. To the neoliberalism of the right corresponded a new social democratic neoliberalism, retaining nearly all its miserly and punitive politics toward working people. It was combined with a social liberalism championing feminism, environmentalism, anti-racism and LGBTQ issues, all with a pronounced middle class flavour and very little demand on the public purse. A final element was what Peter Gowan called “neoliberal cosmopolitanism”, the latter day avatar of liberal internationalism. Both were versions of imperialism, a smug and settled attitude that the rest of the world needed western liberal (that is to say, capitalist) ideals and organization. If it was not willing to recognise it, it must be forced to so do. The former only distinguished itself by its even greater zeal such as that exemplified by the Tony Blair government’s criminal act of prosecuting war in Iraq on falsified evidence. Neoliberal cosmopolitanism resonated with ‘globalization’ and support for neoliberal Europeanism.

…And the Working Class Turn to Populism

With this accommodation, social democratic parties, the parties of the working class, cut themselves adrift from the concerns of vast swaths of their core constituency. While the more prosperous sections of the working class had been abandoning their historic parties throughout the neoliberal period, now something qualitatively new was happening. The discontents of neoliberalism, whose numbers swelled greatly under the ‘austerity’ of the past decade, a politics in which working people paid the price of bailing out big banks and the one percent after 2008 and who should have been organised by parties of the left, were abandoned by them. While the PMC elite establishment promoted globalization and neoliberal European integration—in effect world- and Europe-wide opportunities for themselves and their credentialed children—the discontents of such neoliberalism swelled behind Trump and Brexit. Unrepresented by the parties that, by all rights, should have represented them, they began voting in sufficiently significant numbers for right wing populists. In some countries, they took over parties of the right, as in the UK and the US and came to power. In others, they challenged these parties and transformed the political landscape, as in Germany or Austria. As working class allegiance to social democracy loosened, even as their grievances deepened, they were ripe for the picking of those who sought to exploit society’s deep divisions without having the slightest intention of healing them.

Despite the resulting victories of the Trumps and the Johnsons, there has been little re-thinking on the part of the credentialed social democrats. Along with the other members of their class, they now constitute a single cross-party establishment in most Western countries, facing a revolt from the right and, where some sort of left-wing politics has survived, from the left. The problems for left politics that result are, perhaps, most clearly visible in the fate of Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. It was clear as day throughout his agonising time as leader of the Labour Party that the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP), dominated by the credentialed PMC members, were resolutely opposed to his left-wing leadership. Now we know that it went so far as to sabotage the 2017 general election in the hopes of replacing him as leader thereafter.

Class and Left Politics Today

However, the problem of the distance between the credentialed classes and working people poses for left-wing politics does not end there. Corbyn’s leadership is famous for having attracted 400,000 odd new members into the Labour Party, making it the largest party in Europe. These new entrants, overwhelmingly the credentialed or soon-to-be-credentialed post-secondary students attracted to Corbyn’s left-wing and environmental positions, not least thanks to the generational inequities they suffer, were actually or aspirationally members of the internationally mobile, socially liberal, credentialed classes who are Europeanists and ‘globalisers’.

On the critical issues of ‘globalization’ and European integration, their attitudes, and those of most members of Momentum, the left-wing pressure group of the party, align with those of the PMC establishment in the PLP. Corbyn was able to transcend this contradiction in the 2017 election by making his vision of Britain the main election platform. However, in the two years that followed, the PLP leadership’s unrelenting attacks on Corbyn, particularly for his alleged anti-Semitism, intensified and one major result was that the party had to bow to the PLP establishment and agree to a Second Referendum, something that the rest of the party also agreed to. This could now be portrayed as a betrayal by Johnson and his ruthless advisors to tip the election in their favour in historic Labour constituencies. With the election of Keir Starmer, the Labour Party, albeit much changed, is safely back in the hands of its PMC leadership.

Today the PMCs of various countries, having turned all mainstream politics into a politics of neoliberalism, form a solid cross party phalanx, a veritable establishment, operating across parties, corporate foundations and think tanks. Their unified discourse is policed by forms of censorship more effective than any in the most dystopian visions of the Soviet Union or the People’s Republic of China or even the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

Operating with the carrots of preferment and pay, and the sticks of being silenced (as with Chelsea Manning, Julian Assange and Edward Snowden) or shunned, as with so many critical writers branded ‘conspiracy theorists’ or ‘dangerous’ or simply loony. Equating the populism of a Johnson or Trump with the class politics of left leaders such as Corbyn or Sanders or Maduro as versions of populism, they also strike at both major forms of challenge to their power. Many sections of the left also act as freelance vigilantes for this establishment, particularly by attacking those questioning this neoliberal consensus, whether on Israel-Palestine or wars of ‘democracy promotion’.

Capitalism and Imperialism

Why were people farther to the left, particularly Marxists—after all Marx remains the intellectual lodestar of left politics—unable to prevent left politics from coming to this unfortunate point? Of course, their small numbers are part of the explanation, though leadership has never been about large numbers. One critical reason, which may appear, prima facie, rather esoteric, lies in their inadequate understanding of capitalism. It has led to a misunderstanding of its relationship with imperialism and the course of world revolution and to an aversion to thinking about organising production, something that would require planning and party, both long eschewed by the left. Esoteric though it may seem, this problem must be resolved if the left is to realise its new hope in the present crisis.

Capitalism is inherently imperialist, no matter how much mainstream Western thinking and certain strands of Marxism (yes!) deny it. Its contradictions, such as overproduction of capital and commodities, and reliance on cheap inputs, make it so. So, in addition to the working classes in the homelands of capitalism, it also exploits the working population of the Third World, in more and less easy alliances with its ruling classes. However, going back to the Marxism of the Second International, Marx’s understanding of capitalisms’ contradictions and the value analysis which generated it, were jettisoned as Marxists fell under the influence of the emerging neoclassical economics even though its explicit purpose was to oppose Marxism. A new ‘Marxist Economics’ emerged, pursuing what Bukharin called a ‘policy of theoretical reconciliation’ with neoclassical economics. On the strength of this, most Marxists judged that Marx’s analysis of capitalism as contradictory value production suffered form a ‘transformation problem’. It could not ‘transform values into prices’, entirely ignoring the fact that prices were the only forms in which values expressed themselves and its distortions were necessary to the dynamics of capitalism. Marxist economists also insisted that Marx never claimed that paucity of demand was a problem under capitalism despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary and that Marx was wrong about the tendency of profits to fall.

This is why Marxist understandings have remained divorced form Marx’s account of capitalism as necessarily imperialist contradictory value production. Either they, like the Monthly Review school, have taken imperialism seriously but studied in only eclectic relation to Marx’s theoretical analysis or, like the Brennerite ‘Political Marxism’ that is closely associated with New Left Review, they have denied the necessity of the relation altogether. The former school dominated left understanding in the Golden Age period, while the latter in the neoliberal period.

Planning, Capitalism and Socialism

This divorce between most Marxist economists and Marx’s analysis has been critically consequential for the left’s domestic as well as international understanding and strategy. Domestically, with its contradiction-free notion of capitalism, the left has entertained a Schumpeterian rather than Marxist conception of capitalism, one that is productively superior to other social forms, past or future, capable of developing the forces of production forever. Since, as per this understanding, a Promethean capitalism cannot be bettered by any sort of planned economy, what counts as the left’s economic strategy is focused on redistribution. This breezy unconcern about production and productivity also forgets that the key reason for the apparent prosperity of the west, is not any allegedly Promethean productivity, but imperialism. In the neoliberal age in particular, precisely when the left detached itself from its concern with imperialism, the effect of stagnating real wages has been alleviated by cheap agricultural and light industrial products from the Third World, whose working populations have suffered even lower wages and prices and worse fates.

In so far as it has any conception of a socialist productive economy, it is some sort of decentralised world of small, cooperative and/or worker-managed enterprises. This vision has not altered very much since Marx excoriated its foremost representative, Pierre Joseph Proudhon. Essentially a petty bourgeois socialism, complete with contemporary hi-tech versions, this vision considers the only freedom worth having to be that of not being a wage worker, the ultimate source of petty-bourgeois pride. It fears that any “general organization of labour in society … would turn the whole of society into a [capitalist] factory” (Marx 1867/1977, 477) and so can only think of any general organization of labour to be the generalization of the proletarian subordination they fear rather than as a socialized, collective, autonomy of all.

The vision of decentralised but still market based small, cooperative and worker managed firms is precisely the sort of economy that is invoked, as Marx argued, to legitimise capitalism. However, such as capitalism, if it ever existed, has soon given way to the full blown capitalism of big, monopolistic and exploitative enterprises and certainly can be guaranteed to do so in contemporary technological conditions. This is not an alternative to capitalism, it is capitalism. Moreover, the allergy to socialist planning today also involves an acceptance of the capitalist planning without which the authoritarian corporate behemoths that bestride our economies could not function. The allergy to socialist planning also ignores how the possibilities contained in today’s information and communication technologies are incompatible with capitalism while their full realization can involve sophisticated democratic planning.

Parties or Network Politics?

The illusion that left economic strategy does not need to involve planning corresponds to a political one, that left politics does not need parties. Social movements and NGOs, uncoordinated with one another are supposed to suffice. Such network politics underestimates two necessities, both critically important to challenging capitalism and building socialism. The first should be clear from the above, the necessity of a coherent vision of how production will be organised in a socialist economy. While no one would advocate the sort of dystopian hyper-centralised planning of the anti-communist imagination, while every effort can and should be made to decentralise and to create the feedback loops (now enabled by information technology) that will make planning more responsive to popular needs, a certain degree of central planning and decision making in what will remain national economies for a long time, will be inevitable.

Secondly, any revolution or even advance towards one will have to take into account the necessity of preparing to take on the inevitable counterrevolution that will be mounted by metropolitan capital in any revolutionary situation, as the Russians, the Chinese, the Vietnamese, the Cubans and down to the Venezuelans today have found out (and here we are not counting the fate of non-socialist assertions against imperialism).

Rather than recognising the necessity of this minimum of centralization without which socialist societies can neither plan production nor resist imperialism, most of the left condemns it as an authoritarian denial of liberal freedoms. Such a left cannot go beyond the bourgeois freedoms that kills.

The Left, Nations and Anti-Imperialism

Internationally, this contradiction-free understanding of capitalism has made the left unable to understand the dynamics of world revolution, theoretically and historically. Theoretically, socialist revolutions will necessarily involve both national as well as class struggles. The division of the world into nation states is the result of the uneven and combined development of capitalism. It is rooted in capitalism’s contradictions. They require powerful capitalist countries to seek to export excess commodities and capital and to avoid inevitable cost push inflation that would undermine its necessarily monetary economy by importing cheap(ened) raw materials. The same logic also requires countries that would avoid the deindustrialising and impoverishing fate to resist by becoming ‘contender’ or ‘crustacean’ nations, planning production domestically and regulating trade and capital flows internationally.

The dialectic of uneven and combined development has ensured that the international relations of capitalism will be those of struggles between imperialist nations, the most powerful capitalist nations, and others, socialist or capitalist, resisting its assaults more and less successfully. Resistance to imperialism, even when it takes non-socialist forms, can contribute to the progress of the world revolution. When capitalist or comprador regimes in the Third World are forced to take progressive and anti-imperialist postures due to popular pressures, they can, as witnessed in the decolonised Third World in the decades after the Second World War, improve the conditions of working people and narrow the options of metropolitan capital.

Where stronger, socialist, forms of resistance to imperialism are possible, socialist forces must not only “first of all settle matters with its own bourgeoisie”, but also hold their ground against the forces of imperialism which will inevitably seek to crush them and extend solidarity to friendly nations, socialist or capitalist, pitted against imperialism before socialism can triumph worldwide.

Historically, the already-discussed limitations of the left in the homelands of capitalism have ensured that the record of revolutions so far has taken a broadly unanticipated turn. All of them have occurred among countries outside the imperial core in resistance to it and have had to be socialist as well as nationalist. They have, moreover, had to face the task of creating prosperous and equal societies capable of commanding the strong forms of legitimacy required in the face of relentless imperial pressure. Ground realities as well as imperial pressures have deformed these socialisms as much as the doctrinal deficiencies most on the Western left finger to deny solidarity to these regimes while dismissing their genuine historical achievements.

This tendency and the aversion to planning, party and the state have been mutually reinforcing. They have resulted in the blank cosmopolitanism of the Western left, which leaves them credulous before narratives such as ‘globalization’ and ‘empire’ and open to supporting or at least remaining indifferent to, imperialist ventures against alleged ‘brutal dictators’ in the name of ‘human rights’ and ‘democracy’. Such credulity has also prevented the Western left from appreciating the real significance of the rise of China, let alone the growth, however modest, of other countries of the Third World. This last point is the subject of Part V while the next part surveys the right forces in the battlefield of pandemic politics.

Radhika Desai is a professor in the Department of Political Studies at the University of Manitoba and currently serves as the director of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group.