By Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya

This article first published by GR in November 2006 is of particular relevance to an understanding of the ongoing process of destabilization and political fragmentation of Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

Washington’s strategy consists in breaking up Syria and Iraq.

* * *

“Hegemony is as old as Mankind…” -Zbigniew Brzezinski, former U.S. National Security Advisor

The term “New Middle East” was introduced to the world in June 2006 in Tel Aviv by U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice (who was credited by the Western media for coining the term) in replacement of the older and more imposing term, the “Greater Middle East.”

This shift in foreign policy phraseology coincided with the inauguration of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) Oil Terminal in the Eastern Mediterranean. The term and conceptualization of the “New Middle East,” was subsequently heralded by the U.S. Secretary of State and the Israeli Prime Minister at the height of the Anglo-American sponsored Israeli siege of Lebanon. Prime Minister Olmert and Secretary Rice had informed the international media that a project for a “New Middle East” was being launched from Lebanon.

This announcement was a confirmation of an Anglo-American-Israeli “military roadmap” in the Middle East. This project, which has been in the planning stages for several years, consists in creating an arc of instability, chaos, and violence extending from Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria to Iraq, the Persian Gulf, Iran, and the borders of NATO-garrisoned Afghanistan.

The “New Middle East” project was introduced publicly by Washington and Tel Aviv with the expectation that Lebanon would be the pressure point for realigning the whole Middle East and thereby unleashing the forces of “constructive chaos.” This “constructive chaos” –which generates conditions of violence and warfare throughout the region– would in turn be used so that the United States, Britain, and Israel could redraw the map of the Middle East in accordance with their geo-strategic needs and objectives.

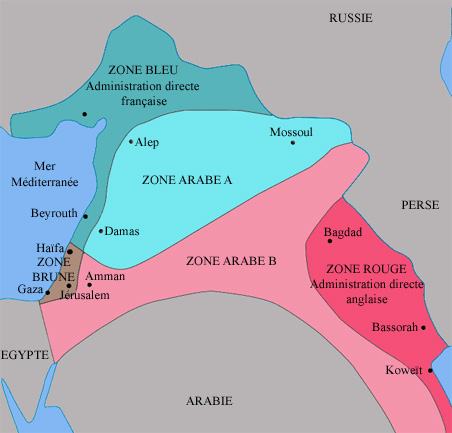

New Middle East Map

Secretary Condoleezza Rice stated during a press conference that “[w]hat we’re seeing here [in regards to the destruction of Lebanon and the Israeli attacks on Lebanon], in a sense, is the growing—the ‘birth pangs’—of a ‘New Middle East’ and whatever we do we [meaning the United States] have to be certain that we’re pushing forward to the New Middle East [and] not going back to the old one.”1 Secretary Rice was immediately criticized for her statements both within Lebanon and internationally for expressing indifference to the suffering of an entire nation, which was being bombed indiscriminately by the Israeli Air Force.

The Anglo-American Military Roadmap in the Middle East and Central Asia

U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s speech on the “New Middle East” had set the stage. The Israeli attacks on Lebanon –which had been fully endorsed by Washington and London– have further compromised and validated the existence of the geo-strategic objectives of the United States, Britain, and Israel. According to Professor Mark Levine the “neo-liberal globalizers and neo-conservatives, and ultimately the Bush Administration, would latch on to creative destruction as a way of describing the process by which they hoped to create their new world orders,” and that “creative destruction [in] the United States was, in the words of neo-conservative philosopher and Bush adviser Michael Ledeen, ‘an awesome revolutionary force’ for (…) creative destruction…”2

Anglo-American occupied Iraq, particularly Iraqi Kurdistan, seems to be the preparatory ground for the balkanization (division) and finlandization (pacification) of the Middle East. Already the legislative framework, under the Iraqi Parliament and the name of Iraqi federalization, for the partition of Iraq into three portions is being drawn out. (See map below)

Moreover, the Anglo-American military roadmap appears to be vying an entry into Central Asia via the Middle East. The Middle East, Afghanistan, and Pakistan are stepping stones for extending U.S. influence into the former Soviet Union and the ex-Soviet Republics of Central Asia. The Middle East is to some extent the southern tier of Central Asia. Central Asia in turn is also termed as “Russia’s Southern Tier” or the Russian “Near Abroad.”

Many Russian and Central Asian scholars, military planners, strategists, security advisors, economists, and politicians consider Central Asia (“Russia’s Southern Tier”) to be the vulnerable and “soft under-belly” of the Russian Federation.3

It should be noted that in his book, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geo-strategic Imperatives, Zbigniew Brzezinski, a former U.S. National Security Advisor, alluded to the modern Middle East as a control lever of an area he, Brzezinski, calls the Eurasian Balkans. The Eurasian Balkans consists of the Caucasus (Georgia, the Republic of Azerbaijan, and Armenia) and Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan) and to some extent both Iran and Turkey. Iran and Turkey both form the northernmost tiers of the Middle East (excluding the Caucasus4) that edge into Europe and the former Soviet Union.

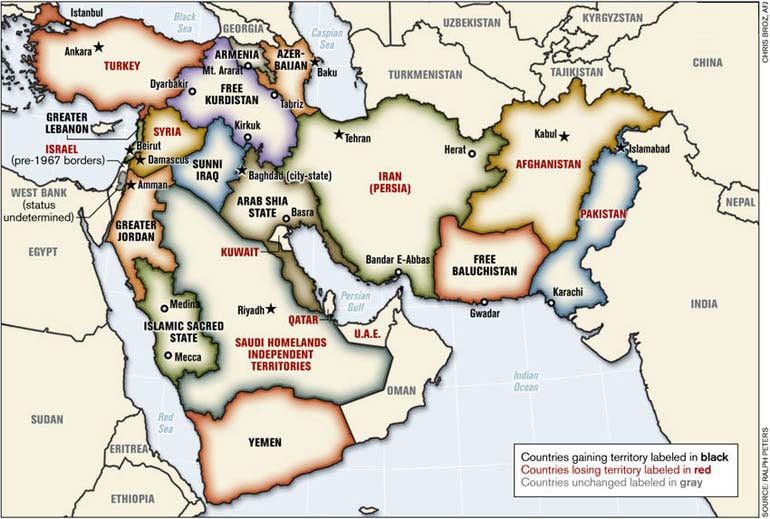

The Map of the “New Middle East”

A relatively unknown map of the Middle East, NATO-garrisoned Afghanistan, and Pakistan has been circulating around strategic, governmental, NATO, policy and military circles since mid-2006. It has been causally allowed to surface in public, maybe in an attempt to build consensus and to slowly prepare the general public for possible, maybe even cataclysmic, changes in the Middle East. This is a map of a redrawn and restructured Middle East identified as the “New Middle East.”

MAP OF THE NEW MIDDLE EAST

Note: The following map was prepared by Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Peters. It was published in the Armed Forces Journal in June 2006, Peters is a retired colonel of the U.S. National War Academy. (Map Copyright Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Peters 2006).

Although the map does not officially reflect Pentagon doctrine, it has been used in a training program at NATO’s Defense College for senior military officers. This map, as well as other similar maps, has most probably been used at the National War Academy as well as in military planning circles.

This map of the “New Middle East” seems to be based on several other maps, including older maps of potential boundaries in the Middle East extending back to the era of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson and World War I. This map is showcased and presented as the brainchild of retired Lieutenant-Colonel (U.S. Army) Ralph Peters, who believes the redesigned borders contained in the map will fundamentally solve the problems of the contemporary Middle East.

The map of the “New Middle East” was a key element in the retired Lieutenant-Colonel’s book, Never Quit the Fight, which was released to the public on July 10, 2006. This map of a redrawn Middle East was also published, under the title of Blood Borders: How a better Middle East would look, in the U.S. military’s Armed Forces Journal with commentary from Ralph Peters.5

It should be noted that Lieutenant-Colonel Peters was last posted to the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, within the U.S. Defence Department, and has been one of the Pentagon’s foremost authors with numerous essays on strategy for military journals and U.S. foreign policy.

It has been written that Ralph Peters’ “four previous books on strategy have been highly influential in government and military circles,” but one can be pardoned for asking if in fact quite the opposite could be taking place. Could it be Lieutenant-Colonel Peters is revealing and putting forward what Washington D.C. and its strategic planners have anticipated for the Middle East?

The concept of a redrawn Middle East has been presented as a “humanitarian” and “righteous” arrangement that would benefit the people(s) of the Middle East and its peripheral regions. According to Ralph Peter’s:

International borders are never completely just. But the degree of injustice they inflict upon those whom frontiers force together or separate makes an enormous difference — often the difference between freedom and oppression, tolerance and atrocity, the rule of law and terrorism, or even peace and war.

The most arbitrary and distorted borders in the world are in Africa and the Middle East. Drawn by self-interested Europeans (who have had sufficient trouble defining their own frontiers), Africa’s borders continue to provoke the deaths of millions of local inhabitants. But the unjust borders in the Middle East — to borrow from Churchill — generate more trouble than can be consumed locally.

While the Middle East has far more problems than dysfunctional borders alone — from cultural stagnation through scandalous inequality to deadly religious extremism — the greatest taboo in striving to understand the region’s comprehensive failure isn’t Islam, but the awful-but-sacrosanct international boundaries worshipped by our own diplomats.

Of course, no adjustment of borders, however draconian, could make every minority in the Middle East happy. In some instances, ethnic and religious groups live intermingled and have intermarried. Elsewhere, reunions based on blood or belief might not prove quite as joyous as their current proponents expect. The boundaries projected in the maps accompanying this article redress the wrongs suffered by the most significant “cheated” population groups, such as the Kurds, Baluch and Arab Shia [Muslims], but still fail to account adequately for Middle Eastern Christians, Bahais, Ismailis, Naqshbandis and many another numerically lesser minorities. And one haunting wrong can never be redressed with a reward of territory: the genocide perpetrated against the Armenians by the dying Ottoman Empire.

Yet, for all the injustices the borders re-imagined here leave unaddressed, without such major boundary revisions, we shall never see a more peaceful Middle East.

Even those who abhor the topic of altering borders would be well-served to engage in an exercise that attempts to conceive a fairer, if still imperfect, amendment of national boundaries between the Bosphorus and the Indus. Accepting that international statecraft has never developed effective tools — short of war — for readjusting faulty borders, a mental effort to grasp the Middle East’s “organic” frontiers nonetheless helps us understand the extent of the difficulties we face and will continue to face. We are dealing with colossal, man-made deformities that will not stop generating hatred and violence until they are corrected. 6

(emphasis added)

“Necessary Pain”

Besides believing that there is “cultural stagnation” in the Middle East, it must be noted that Ralph Peters admits that his propositions are “draconian” in nature, but he insists that they are necessary pains for the people of the Middle East. This view of necessary pain and suffering is in startling parallel to U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s belief that the devastation of Lebanon by the Israeli military was a necessary pain or “birth pang” in order to create the “New Middle East” that Washington, London, and Tel Aviv envision.

Moreover, it is worth noting that the subject of the Armenian Genocide is being politicized and stimulated in Europe to offend Turkey.7

The overhaul, dismantlement, and reassembly of the nation-states of the Middle East have been packaged as a solution to the hostilities in the Middle East, but this is categorically misleading, false, and fictitious. The advocates of a “New Middle East” and redrawn boundaries in the region avoid and fail to candidly depict the roots of the problems and conflicts in the contemporary Middle East. What the media does not acknowledge is the fact that almost all major conflicts afflicting the Middle East are the consequence of overlapping Anglo-American-Israeli agendas.

Many of the problems affecting the contemporary Middle East are the result of the deliberate aggravation of pre-existing regional tensions. Sectarian division, ethnic tension and internal violence have been traditionally exploited by the United States and Britain in various parts of the globe including Africa, Latin America, the Balkans, and the Middle East. Iraq is just one of many examples of the Anglo-American strategy of “divide and conquer.” Other examples are Rwanda, Yugoslavia, the Caucasus, and Afghanistan.

Amongst the problems in the contemporary Middle East is the lack of genuine democracy which U.S. and British foreign policy has actually been deliberately obstructing. Western-style “Democracy” has been a requirement only for those Middle Eastern states which do not conform to Washington’s political demands. Invariably, it constitutes a pretext for confrontation. Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan are examples of undemocratic states that the United States has no problems with because they are firmly alligned within the Anglo-American orbit or sphere.

Additionally, the United States has deliberately blocked or displaced genuine democratic movements in the Middle East from Iran in 1953 (where a U.S./U.K. sponsored coup was staged against the democratic government of Prime Minister Mossadegh) to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Turkey, the Arab Sheikdoms, and Jordan where the Anglo-American alliance supports military control, absolutists, and dictators in one form or another. The latest example of this is Palestine.

The Turkish Protest at NATO’s Military College in Rome

Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Peters’ map of the “New Middle East” has sparked angry reactions in Turkey. According to Turkish press releases on September 15, 2006 the map of the “New Middle East” was displayed in NATO’s Military College in Rome, Italy. It was additionally reported that Turkish officers were immediately outraged by the presentation of a portioned and segmented Turkey.8 The map received some form of approval from the U.S. National War Academy before it was unveiled in front of NATO officers in Rome.

The Turkish Chief of Staff, General Buyukanit, contacted the U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Peter Pace, and protested the event and the exhibition of the redrawn map of the Middle East, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.9 Furthermore the Pentagon has gone out of its way to assure Turkey that the map does not reflect official U.S. policy and objectives in the region, but this seems to be conflicting with Anglo-American actions in the Middle East and NATO-garrisoned Afghanistan.

Is there a Connection between Zbigniew Brzezinski’s “Eurasian Balkans” and the “New Middle East” Project?

The following are important excerpts and passages from former U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski’s book, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geo-strategic Imperatives. Brzezinski also states that both Turkey and Iran, the two most powerful states of the “Eurasian Balkans,” located on its southern tier, are “potentially vulnerable to internal ethnic conflicts [balkanization],” and that, “If either or both of them were to be destabilized, the internal problems of the region would become unmanageable.”10

It seems that a divided and balkanized Iraq would be the best means of accomplishing this. Taking what we know from the White House’s own admissions; there is a belief that “creative destruction and chaos” in the Middle East are beneficial assets to reshaping the Middle East, creating the “New Middle East,” and furthering the Anglo-American roadmap in the Middle East and Central Asia:

In Europe, the Word “Balkans” conjures up images of ethnic conflicts and great-power regional rivalries. Eurasia, too, has its “Balkans,” but the Eurasian Balkans are much larger, more populated, even more religiously and ethnically heterogenous. They are located within that large geographic oblong that demarcates the central zone of global instability (…) that embraces portions of southeastern Europe, Central Asia and parts of South Asia [Pakistan, Kashmir, Western India], the Persian Gulf area, and the Middle East.

The Eurasian Balkans form the inner core of that large oblong (…) they differ from its outer zone in one particularly significant way: they are a power vacuum.Although most of the states located in the Persian Gulf and the Middle East are also unstable, American power is that region’s [meaning the Middle East’s] ultimate arbiter. The unstable region in the outer zone is thus an area of single power hegemony and is tempered by that hegemony. In contrast, the Eurasian Balkans are truly reminiscent of the older, more familiar Balkans of southeastern Europe: not only are its political entities unstable but they tempt and invite the intrusion of more powerful neighbors, each of whom is determined to oppose the region’s domination by another. It is this familiar combination of a power vacuum and power suction that justifies the appellation “Eurasian Balkans.”

The traditional Balkans represented a potential geopolitical prize in the struggle for European supremacy.The Eurasian Balkans, astride the inevitably emerging transportation network meant to link more directly Eurasia’s richest and most industrious western and eastern extremities, are also geopolitically significant. Moreover, they are of importance from the standpoint of security and historical ambitions to at least three of their most immediate and more powerful neighbors, namely, Russia, Turkey, and Iran, with China also signaling an increasing political interest in the region. But the Eurasian Balkans are infinitely more important as a potential economic prize: an enormous concentration of natural gas and oil reserves is located in the region, in addition to important minerals, including gold.

The world’s energy consumption is bound to vastly increase over the next two or three decades. Estimates by the U.S. Department of Energy anticipate that world demand will rise by more than 50 percent between 1993 and 2015, with the most significant increase in consumption occurring in the Far East.The momentum of Asia’s economic development is already generating massive pressures for the exploration and exploitation of new sources of energy, and the Central Asian region and the Caspian Sea basin are known to contain reserves of natural gas and oil that dwarf those of Kuwait, the Gulf of Mexico, or the North Sea.

Access to that resource and sharing in its potential wealth represent objectives that stir national ambitions, motivate corporate interests, rekindle historical claims, revive imperial aspirations, and fuel international rivalries. The situation is made all the more volatile by the fact that the region is not only a power vacuum but is also internally unstable.

(…)

The Eurasian Balkans include nine countries that one way or another fit the foregoing description, with two others as potential candidates. The nine are Kazakstan [alternative and official spelling of Kazakhstan] , Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia—all of them formerly part of the defunct Soviet Union—as well as Afghanistan.

The potential additions to the list are Turkey and Iran, both of them much more politically and economically viable, both active contestants for regional influence within the Eurasian Balkans, and thus both significant geo-strategic players in the region. At the same time, both are potentially vulnerable to internal ethnic conflicts. If either or both of them were to be destabilized, the internal problems of the region would become unmanageable, while efforts to restrain regional domination by Russia could even become futile. 11

(emphasis added)

Redrawing the Middle East

The Middle East, in some regards, is a striking parallel to the Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe during the years leading up the First World War. In the wake of the the First World War the borders of the Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe were redrawn. This region experienced a period of upheaval, violence and conflict, before and after World War I, which was the direct result of foreign economic interests and interference.

The reasons behind the First World War are more sinister than the standard school-book explanation, the assassination of the heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian (Habsburg) Empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo. Economic factors were the real motivation for the large-scale war in 1914.

Norman Dodd, a former Wall Street banker and investigator for the U.S. Congress, who examined U.S. tax-exempt foundations, confirmed in a 1982 interview that those powerful individuals who from behind the scenes controlled the finances, policies, and government of the United States had in fact also planned U.S. involvement in a war, which would contribute to entrenching their grip on power.

The following testimonial is from the transcript of Norman Dodd’s interview with G. Edward Griffin;

We are now at the year 1908, which was the year that the Carnegie Foundation began operations. And, in that year, the trustees meeting, for the first time, raised a specific question, which they discussed throughout the balance of the year, in a very learned fashion. And the question is this: Is there any means known more effective than war, assuming you wish to alter the life of an entire people? And they conclude that, no more effective means to that end is known to humanity, than war. So then, in 1909, they raise the second question, and discuss it, namely, how do we involve the United States in a war?

Well, I doubt, at that time, if there was any subject more removed from the thinking of most of the people of this country [the United States], than its involvement in a war. There were intermittent shows [wars] in the Balkans, but I doubt very much if many people even knew where the Balkans were. And finally, they answer that question as follows: we must control the State Department.

And then, that very naturally raises the question of how do we do that? They answer it by saying, we must take over and control the diplomatic machinery of this country and, finally, they resolve to aim at that as an objective. Then, time passes, and we are eventually in a war, which would be World War I. At that time, they record on their minutes a shocking report in which they dispatch to President Wilson a telegram cautioning him to see that the war does not end too quickly. And finally, of course, the war is over.

At that time, their interest shifts over to preventing what they call a reversion of life in the United States to what it was prior to 1914, when World War I broke out. (emphasis added)

The redrawing and partition of the Middle East from the Eastern Mediterranean shores of Lebanon and Syria to Anatolia (Asia Minor), Arabia, the Persian Gulf, and the Iranian Plateau responds to broad economic, strategic and military objectives, which are part of a longstanding Anglo-American and Israeli agenda in the region.

The Middle East has been conditioned by outside forces into a powder keg that is ready to explode with the right trigger, possibly the launching of Anglo-American and/or Israeli air raids against Iran and Syria. A wider war in the Middle East could result in redrawn borders that are strategically advantageous to Anglo-American interests and Israel.

NATO-garrisoned Afghanistan has been successfully divided, all but in name. Animosity has been inseminated in the Levant, where a Palestinian civil war is being nurtured and divisions in Lebanon agitated. The Eastern Mediterranean has been successfully militarized by NATO. Syria and Iran continue to be demonized by the Western media, with a view to justifying a military agenda. In turn, the Western media has fed, on a daily basis, incorrect and biased notions that the populations of Iraq cannot co-exist and that the conflict is not a war of occupation but a “civil war” characterised by domestic strife between Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds.

Attempts at intentionally creating animosity between the different ethno-cultural and religious groups of the Middle East have been systematic. In fact, they are part of a carefully designed covert intelligence agenda.

Even more ominous, many Middle Eastern governments, such as that of Saudi Arabia, are assisting Washington in fomenting divisions between Middle Eastern populations. The ultimate objective is to weaken the resistance movement against foreign occupation through a “divide and conquer strategy” which serves Anglo-American and Israeli interests in the broader region.

Mahdi Darius Nazemroaya specializes in Middle Eastern and Central Asian affairs. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Notes

1 Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Special Briefing on the Travel to the Middle East and Europe of Secretary Condoleezza Rice (Press Conference, U.S. State Department, Washington, D.C., July 21, 2006).

http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2006/69331.htm

2 Mark LeVine, “The New Creative Destruction,” Asia Times, August 22, 2006.

http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/HH22Ak01.html

3 Andrej Kreutz, “The Geopolitics of post-Soviet Russia and the Middle East,” Arab Studies Quarterly (ASQ) (Washington, D.C.: Association of Arab-American University Graduates, January 2002).

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2501/is_1_24/ai_93458168/pg_1

4 The Caucasus or Caucasia can be considered as part of the Middle East or as a separate region

5 Ralph Peters, “Blood borders: How a better Middle East would look,” Armed Forces Journal (AFJ), June 2006.

http://www.armedforcesjournal.com/2006/06/1833899

6 Ibid.

7 Crispian Balmer, “French MPs back Armenia genocide bill, Turkey angry, Reuters, October 12, 2006; James McConalogue, “French against Turks: Talking about Armenian Genocide,” The Brussels Journal, October 10, 2006.

http://www.brusselsjournal.com/node/1585

8 Suleyman Kurt, “Carved-up Map of Turkey at NATO Prompts U.S. Apology,” Zaman (Turkey), September 29, 2006.

http://www.zaman.com/?bl=international&alt=&hn=36919

9 Ibid.

10 Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geo-strategic Imperatives (New York City: Basic Books, 1997).

11 Ibid.