By Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda

January 17, 2022

The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by Hans M. Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project with the Federation of American Scientists, and Matt Korda, a senior research associate with the project. The Nuclear Notebook column has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. This issue’s column examines Israel’s nuclear arsenal, which we estimate includes a stockpile of roughly 90 warheads. Israel neither officially confirms nor denies that it possesses nuclear weapons, and our estimate is therefore largely based on calculations of Israel’s stockpile of weapon-grade plutonium and its inventory of operational nuclear-capable delivery systems.

To download a free PDF of this article, click here.

To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns, click here.

Conducting research on Israeli nuclear weapons has historically been very challenging, not least because Israel purposely does not acknowledge its own possession of nuclear weapons. Moreover, Western governments normally do not include Israel in their descriptions of nuclear-armed states. Additionally, Israeli nuclear whistleblowers have faced significant penalties; in 1986, former nuclear technician Mordechai Vanunu was kidnapped by Israeli intelligence services and spent 18 years in prison after giving a detailed interview about Israel’s nuclear program to the Sunday Times (Myre 2004). This chilling effect means that individuals with knowledge of Israel’s nuclear program have been understandably reluctant to provide on-the-record information, which dilutes the ability of open-source researchers to analyze Israel’s nuclear forces. Thankfully, over the past two decades, historians like Avner Cohen and William Burr have contributed invaluable research that has made previously unknown nuances of Israel’s opaque nuclear policy available to the public.1

Additionally, since 1997 a US law known as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment has prohibited US companies from publishing satellite imagery at a resolution that is “no more detailed or precise than satellite imagery of Israel that is available from commercial sources.” For decades, this has meant that the majority of commercially available satellite imagery of Israel has been limited to a resolution of approximately two meters, making it very difficult to analyze in detail. However, in June 2020, the US Commercial Remote Sensing Regulatory Affairs Office announced that it would now allow commercial imagery providers to offer enhanced imagery of Israel at a resolution of 0.4 meters (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 2020). The move was made in order to bring American imagery providers in line with their foreign counterparts, which had already been producing imagery at that level for several years. As a result, we have incorporated higher-resolution imagery into this article.

The history of Israel’s nuclear program

The Israeli nuclear weapons program dates back to the mid-1950s, when the country’s first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, began to explore a nuclear insurance plan in order to offset the combined conventional superiority of Israel’s neighboring Arab states. As historian Avner Cohen writes, “Ben Gurion’s determination to launch the nuclear project was the result of strategic intuition and obsessive fears, not of a well-thought-out plan. He believed Israel needed nuclear weapons as insurance if it could no longer compete with the Arabs in an arms race and as a weapon of last resort in case of an extreme military emergency” (Cohen 1998). Ben Gurion tapped Shimon Peres––who would later become Israel’s prime minister––to lead Israel’s nuclear program. Under Peres’ stewardship, Israel purchased a substantial package, including a research reactor and plutonium separation technology, from France in 1957, as well as 20 tons of heavy water from Norway in 1959 (Cohen and Burr 2015). The ground for the Negev Nuclear Research Center was broken near Dimona in early 1958.

Although the Negev center was always intended for the development of nuclear weapons, the United States did not become aware of its true purpose for another decade, even after US intelligence became aware of its construction in 1958 (Cohen and Burr 2021). This was largely due to a highly successful Israeli deception and disinformation campaign aimed at convincing US inspectors that the complex was for civilian use. The deception campaign included lying to US officials by first telling them that the Negev center was the site of a textile factory. Next, they said that the Negev center was instead a purely civilian research center that did not contain the chemical reprocessing plant it would need to produce nuclear weapons (Cohen and Burr 2015). Investigative journalist Seymour Hersh’s book, The Samson Option, includes a short description of the Israeli deception scheme:

“A false control room was constructed at Dimona, complete with false control panels and computer-driven measuring devices that seemed to be gauging the thermal output of a twenty-four-megawatt reactor (as Israel claimed Dimona to be) in full operation. There were extensive practice sessions in the fake control room, as Israeli technicians sought to avoid any slips when the Americans arrived. The goal was to convince the inspectors that no chemical reprocessing plant existed or was possible” (Hersh 1991).

Several factors appear to have contributed to the United States’ susceptibility to the Israeli deception campaign. Given Israel’s strong resistance to a formalized inspection protocol, the United States declined to pressure Israel to commit to one, instead acquiescing to Israel’s preference to consider the arrangement as “scientific visits” instead of “inspections.”

Additionally, declassified documents suggest that the United States was unaware of the degree of Franco-Israeli cooperation, and particularly the Negev center package’s inclusion of a large underground chemical reprocessing plant for extracting weapons-grade plutonium. At the time, American intelligence incorrectly believed that it would be able to detect this critical facility’s construction through on-site visits; however, without an agreed framework for comprehensive inspections, US visiting scientists were ill-equipped to assess the complete scope of the construction efforts at Negev. Additionally, as Avner Cohen suggests, the visiting scientists’ mission “was not to challenge what they were told, but to verify it” (Cohen 1998, 107). As a result, they were unaware––and perhaps unwilling to consider the possibility––that a six-story underground reprocessing facility was being built right under their noses (Cohen and Burr 2021).

The construction of the chemical reprocessing plant was reportedly completed in 1965, and Israel began plutonium production in 1966 (Cohen and Burr 2020). It remains unclear exactly when Israel’s first operational nuclear weapons were completed, although it is believed that Israel may have assembled––or attempted to assemble––its first crude nuclear devices during the May 1967 crisis immediately preceding the Six-Day War.

Nuclear ambiguity

Since the late 1960s, every Israeli government has practiced a policy of nuclear ambiguity. “Amimut,” as it is known, deliberately obscures whether Israel actually possesses nuclear weapons, and if so, how its arsenal is operationalized. Since the mid-1960s, this policy has been publicly expressed—and recently reaffirmed by former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu—as the phrase “We won’t be the first to introduce nuclear weapons into the Middle East” (Netanyahu 2011).

The Israeli government’s interpretation of “introducing” nuclear weapons, however, appears to have so many caveats that the statement itself is rendered essentially meaningless. This is because Israeli policymakers have previously suggested that “introducing” nuclear weapons would necessarily require Israel to test, publicly declare, or actually use its nuclear capability. Given that Israel has not officially done any of those things, the Israeli government can declare that it has not “introduced” nuclear weapons into the region, despite the high likelihood that in reality the country possesses a sizable nuclear arsenal.

Israel’s policy of deliberate ambiguity was enshrined during the country’s negotiations with the United States over the purchase of 50 F-4 Phantom aircraft during the late 1960s. The United States’ and Israel’s competing interpretations over the term “introduce” threatened to derail the arms sale entirely. In a July 1969 memorandum addressed to President Nixon, Henry Kissinger noted that “We and Israel differ on what ‘introducing’ nuclear weapons means. Ambassador Rabin believes only testing and making public the fact of possession constitute ‘introduction.’ We stated in the exchange of letters confirming the Phantom sale that we consider ‘physical possession and control of nuclear arms’ to constitute ‘introduction” (US State Department 1969a).

During a meeting at the Pentagon in November 1968, Israel’s ambassador to the United States, Yitzhak Rabin––who later succeeded Prime Minister Golda Meir as Israeli prime minister––said that “he would not consider a weapon that had not been tested to be a weapon.” Moreover, he said, “There must be a public acknowledgement. The fact that you have got it must be known.” Seeking clarity, US Assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Warnke asked: “Then in your view, an unadvertised, untested nuclear device is not a nuclear weapon?” Rabin responded: “Yes, that is correct.” So, Warnke continued, an advertised but untested device or weapon would constitute introduction? “Yes, that would be introduction,” Rabin confirmed (US Defense Department 1968, 2, 3, 4).

In a follow-up exchange in July 1969, the Nixon administration plainly summarized its own understanding of the term “introduction:” “When Israel says it will not introduce nuclear weapons it means it will not possess such weapons.” The Nixon administration wanted Israel to accept the US definition, but the Meir government didn’t take the bait and instead claimed: “Introduction means the transformation from a non-nuclear weapon country into a nuclear weapon country” (US State Department 1969a). In other words, Israel construed its pledge not to be the first to introduce nuclear weapons to mean that that introduction was not about physical possession but about public acknowledgement of that possession.

Kissinger saw a way out of the disagreement: He informed President Nixon that the Israelis had defined the word “introduction” by “relating it to the NPT [Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty].” Kissinger’s argument was that the “distinction between ‘nuclear-weapon’ and ‘non-nuclear-weapon’ states is the one which the NPT uses in defining the respective obligations of the signatories.” He argued that the NPT negotiations “implicitly left … it up to the conscience of the governments involved” by being “deliberately vague on what precise step would transform a state into a nuclear weapon state after the January 1, 1967 cut-off date used in the treaty to define the nuclear states” (White House 1969b, 1). Kissinger also argued that the NPT does not define what it means to “manufacture” or “acquire” nuclear weapons and concluded that the new Israeli formulation “should put us in a position for the record of being able to say we assume we have Israel’s assurance that it will remain a non-nuclear state as defined in the NPT” (White House 1969b, 1).

Kissinger’s circuitous interpretation provided the United States with a way out of a diplomatic dilemma via a tacit understanding between Nixon and Meir. That is, the United States would no longer pressure Israel to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as long as the Israelis kept their program restrained and invisible—meaning that Israel would not test nuclear weapons and would not acknowledge in public its possession of such weapons.

The goal of this interpretation, stated a July 1969 memo, was to break the diplomatic deadlock while avoiding direct complicity in Israel’s nuclear program, which would have contradicted the United States’ own non-proliferation policies. Specifically, the memo noted that the United States “cannot enforce a precise understanding” of what “introduction” means. Instead, the policy should be to “mainly concern ourselves with building a record that will permit us to defend taking our distance from a nuclear Israel if ever Israel’s use of those weapons threatens to involve us in nuclear confrontation” (White House 1969d). Despite this attempt to distance itself from Israel’s nuclear program, the United States’ clear willingness to turn a blind eye to Israeli proliferation is a double standard that has largely undermined its own credibility when criticizing the nuclear pursuits of other Middle Eastern countries.

After the end of the Cold War, Israel began to fear that the United States’ tacit support for Israel’s undeclared nuclear arsenal would soon fade, given US engagement on a possible Middle East nuclear-weapon free zone. As a result, Israel has reportedly requested that each American president since Bill Clinton sign a letter indicating that any future US arms control efforts would not affect Israel’s nuclear arsenal (Entous 2018a; Entous 2018b).

On a few rare occasions, some Israeli officials have made statements implying that Israel already has nuclear weapons or could “introduce” them very quickly if necessary. The first came in 1974, when then-President Ephraim Katzir stated: “It has always been our intention to develop a nuclear potential … We now have that potential” (Weissman and Krosney 1981, 105). Long after his retirement, in a 1981 New York Times interview, former defense minister Moshe Dayan also came close to violating the nuclear ambiguity taboo when he declared for the record: “We don’t have any atomic bomb now, but we have the capacity, we can do that in a short time.” He reiterated the official policy mantra: “We are not going to be the first ones to introduce nuclear weapons into the Middle East” (New York Times 1981). But his acknowledgement that “we have the capacity” and would quickly produce atomic bombs if Israel’s adversaries acquired nuclear weapons was a hint that Israel had in fact produced all the necessary components to assemble nuclear weapons in a very short time (New York Times 1981).

During a press conference in Washington with US President Bill Clinton and Jordan’s President Hussein in 1994, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin made a similar statement, saying “Israel is not a nuclear country in terms of weapons” and has “committed to the United States for many years not to be the first to introduce nuclear weapons in the context of the Arab-Israeli conflict. But at the same time,” he added, “we cannot be blind to efforts that are made in certain Muslim and Arab countries in this direction. Therefore, I can sum up. We’ll keep our commitment not to be the first to introduce, but we still look ahead to the dangers that others will do it. And we have to be prepared for it” (Rabin 1994; emphasis added).

The ambiguity left by Israel’s refusal to confirm or deny the possession of nuclear weapons prompted the BBC in 2003 to bluntly ask former Prime Minister Shimon Peres: “The term nuclear ambiguity, in some ways it sounds very grand, but isn’t it just a euphemism for deception?” Peres did not answer the question but confirmed the need for deception: “If someone wants to kill you and you use deception to save your life, it’s not immoral. If we wouldn’t [sic] have enemies we wouldn’t need deceptions” (BBC 2003).

Three years later, in a December 2006 interview with German television, then-prime minister Ehud Olmert appeared to compromise the deception when he criticized Iran for aspiring “to have nuclear weapons, as America, France, Israel, Russia” (Williams 2006). The statement, which he made in English, attracted widespread attention because it was seen as an inadvertent admission that Israel possesses nuclear weapons (Williams 2006). A spokesperson for Olmert later said he had been listing not nuclear states but “responsible nations” (Friedman 2006).

Ambiguity is not just about refusing to confirm possession of nuclear weapons but also about refusing to deny it. When asked during a 2011 CNN interview if Israel does not have nuclear weapons, Netanyahu did not answer directly but repeated the policy not to be the first to “introduce” nuclear weapons into the Middle East. Undeterred, the journalist followed up: “But if you take an assumption that other countries have them then that may mean you have them?” Netanyahu didn’t dispute that but implied that the difference is that Israel doesn’t threaten anyone with its arsenal: “Well, it may mean that we don’t pose a threat to anyone. We don’t call for anyone’s annihilation … We don’t threaten to obliterate countries with nuclear weapons but we are threatened with all these threats” (Netanyahu 2011).

Three cases of near-introduction

There have been three distinct incidents during which Israel reportedly came close to “introducing” nuclear weapons to the region, under its own narrow definition. The first instance was during the Six-Day War in June 1967, when according to primary sources and testimonies from former Israeli officials, a small team of commandos was tasked with conducting Operation “Shimson” (Samson)––a planned nuclear detonation for demonstrative purposes––in order to change the Arab coalition’s military calculus. Given Israel’s eventual military success in the war, this plan was never put into action (Cohen 2017).

The second instance reportedly came during the October 1973 Yom Kippur War, when Israeli leaders feared that Syria was about to defeat the Israeli army in the Golan Heights. The rumor first appeared in Time magazine in 1976, was greatly expanded upon in Seymour Hersh’s book The Samson Option in 1991, and several unidentified former US officials allegedly stated in 2002 that Israel put nuclear forces on alert in 1973 (see e.g., Sale 2002).

However, an interview conducted by Avner Cohen with the late Arnan (Sini) Azaryahu in January 2008 calls into question the validity of this rumor. Azaryahu was senior aide and confidant to Yisrael Galili, a minister without portfolio who was Golda Meir’s closest political ally and privy to some of Israel’s most closely held nuclear secrets. In the early afternoon of the second day of the war—October 7, 1973—the Israeli military appeared to be losing the battle against Syrian forces in the Golan Heights. Azaryahu said that the defense minister, Moshe Dayan, asked Meir to authorize initial technical preparations for a “demonstration option”—that is, to ready nuclear weapons for potential use. But Galili and Deputy Prime Minister Yigal Allon argued against the idea, saying Israel would prevail using conventional weapons. According to Azaryahu, Meir sided with her two senior ministers and told Dayan to “forget it” (Cohen 2013). (For analysis of the Azaryahu interview and its implications, see Cohen 2008.)

A study by the Strategic Studies division of the Center for Naval Analyses in April 2013 appeared to confirm Meir’s rejection of Dayan’s “demonstration option” and that Israel’s nuclear forces were not readied. The report states that the authors “did exhaustively scrutinize” the document files of US agencies and archives and interviewed a significant number of officials with firsthand knowledge of the 1973 crisis. Still, it also notes that “(n)one of these searches revealed any documentation of an Israeli alert or clear manipulation of its forces,” and “none of our interviewees, save one, recalled any Israeli nuclear alert or signaling effort” during the Yom Kippur War (Colby et al. 2013, 31–32).

Even so, a single former official recalled seeing an “electronic or signals intelligence report” at the time that “Israel had activated or increased the readiness of its Jericho missile batteries.” That, together with the extreme government secrecy that surrounds Israeli nuclear weapons in general, led the authors of the Center for Naval Analyses study to conclude that “the United States did observe some kind of Israeli nuclear weapons-related activity in the very early days of the war, probably pertaining to Israel’s Jericho ballistic missile force … .” (Colby et al. 2013, 34). The study’s overall assessment was that “Israel appears to have taken preliminary precautionary steps to protect or prepare its nuclear weapons and/or related forces” (Colby et al. 2013, 2; emphasis added).

The conclusion that Israel did something with its nuclear forces in October 1973—although not necessarily place them on full operational alert or prepare for a “demonstration option”—seems similar to the assertion made by Peres in 1995. In an interview with the authors of We All Lost the Cold War, Peres “categorically denied that Jericho missiles were made ready, much less armed. At most, he insisted, there was an operational check. The cabinet never approved any alert of Jericho missiles” (Lebow and Stein 1995, 463, footnote 47).

Evidently, some uncertainty persists about the 1973 events. But then, presumably as well as now, the Israeli warheads were not fully assembled or deployed on delivery systems under normal circumstances but stored under civilian control. And since no official confirmation was made back then either via a test or an announcement, no formal “introduction” of nuclear weapons occurred—at least in the opinion of Israeli officials.

The third potential instance of near-introduction came six years later, on September 22, 1979, when a US surveillance satellite known as the Vela 6911 detected what appeared to be a double-flash from a nuclear test in the southern parts of the Indian Ocean. (For background on the 1979 Vela incident, see Richelson 2006; Cohen and Burr 2016.) Declassified US intelligence documents indicate the prevailing US belief at the time that the flash was the result of an Israeli nuclear test, possibly with South African logistical support. A subsequent 1980 White House panel concluded that the the Vela signal “was probably not from a nuclear event.” However, US scientists and intelligence analysts, who believed that the panel’s conclusions had been heavily biased in order to avoid a political confrontation with Israel, widely rejected these conclusions, according to newly declassified documents. Additionally, the documents appear to suggest that Israeli sources leaked confirmations about the nuclear test to US officials and journalists, but that these claims were either censored or not taken seriously (Cohen and Burr 2016). If the Vela incident was indeed an Israeli nuclear test, it is unclear whether it would constitute the “introduction” of nuclear weapons under Israel’s narrow definition. That is, according to Yitzhak Rabin at the time of the negotiations in the late 1960s, “There must be a public acknowledgement. The fact that you have got it must be known” (US Defense Department 1968). Successive Israeli governments have never publicly acknowledged Israel’s involvement in the Vela incident.

Stockpile size and warhead composition

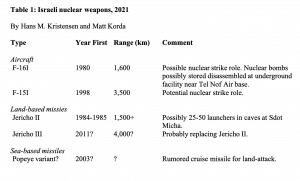

Absent official public information from the Israeli government or intelligence communities of other countries, speculations abound about Israel’s nuclear arsenal. Over the past several decades, news media reports, think tanks, authors, and analysts have presented a wide range of possibilities for the size of the Israeli nuclear stockpile, from 75 warheads to more than 400 warheads. Delivery vehicles for the warheads have been listed as aircraft, ballistic missiles, artillery tactical or battlefield weapons such as artillery shells and landmines, and more recently sea-launched cruise missiles.2 We believe that many of these rumors are inaccurate and that the most credible stockpile number is less than one hundred warheads, probably on the order of 90 warheads for delivery by aircraft, land-based ballistic missiles, and possibly sea-based cruise missiles (see Table 1).

The design and sophistication level of Israel’s nuclear weapons is up for considerable debate. Frank Barnaby, a nuclear physicist who worked at the British Atomic Weapons Research Establishment, interviewed whistleblower and former nuclear technician Mordechai Vanunu in 1986. Barnaby later said that Vanunu’s description of “production at Dimona of lithium-deuteride in the shape of hemispherical shells … raised the question of whether Israel had boosted nuclear weapons in its arsenal” (Barnaby 2004, 4). Although he didn’t think Vanunu had much knowledge about such weapons, Barnaby concluded that “the information he gave suggested that Israel had more advanced nuclear weapons than Nagasaki-type weapons” (Barnaby 2004, 4).

Barnaby did not mention thermonuclear weapons in his 2004 statement, even though he concluded in his book The Invisible Bomb in 1989 that “Israel may have about 35 thermonuclear weapons” (Barnaby 1989, 25). At the time, the director of the CIA apparently did not agree but reportedly indicated that Israel may be seeking to construct a thermonuclear weapon (Cordesman 2005). Yet The Samson Option claims that US weapon designers concluded from Vanunu’s information that “Israel was capable of manufacturing one of the most sophisticated weapons in the nuclear arsenal—a low-yield [two-stage] neutron bomb” (Hersh 1991, 199). The authors of The Nuclear Express in 2009 echoed that claim, stating that the product of Israel’s partnership with South Africa would be “a family of boosted primaries, generic H-bombs, and a specific neutron bomb” (Reed and Stillman 2009, 174).

On the other hand, an April 1987 report by the Institute for Defense Analyses concluded––following a trip to Israel’s Soreq Nuclear Research Center––that Israel lacked the computational sophistication to develop the “codes which detail fission and fusion processes on a microscopic and macroscopic level,” which would be necessary for the development of thermonuclear weapons (Townsley and Robinson 1987).

If Israel was indeed behind the 1979 Vela incident, the country would have conducted only one known atmospheric nuclear test; this could indicate that Israel’s nuclear weapons designs are not particularly sophisticated. It took other nuclear weapon states dozens of elaborate nuclear test explosion experiments to develop sophisticated weapon designs. According to some analysts, however, Israel had “unrestricted access to French nuclear test explosion data” in the 1960s (Cohen 1998, 82–83), so much so that “the French nuclear test in 1960 made two nuclear powers not one” (Weissman and Krosney 1981, 114–117). Until France broke off deep nuclear collaboration with Israel in 1967, France conducted 17 fission warhead tests in Algeria, ranging from a few kilotons to approximately 120 kilotons of explosive yield (CTBTO(n.d.); Nuclear Weapon Archive 2001). France did not conduct its first two-stage thermonuclear test until August 1968.

In sum, it remains highly challenging to assess Israel’s design sophistication for its nuclear weapons. It is hypothetically possible that Israel developed two-stage thermonuclear weapons. Yet a more cautious analysis based upon Israel’s plutonium production, testing history, design skills, force structure, and employment strategy suggests that its arsenal probably consists of single-stage, boosted fission warheads.

Most publicly available estimates of the number of Israeli warheads in its stockpile appear to be derived from a rough calculation of the number of warheads that could hypothetically be created from the amount of plutonium Israel is believed to have produced in its nuclear reactor at Dimona. The technical assessment that accompanied the 1986 Sunday Times article about former nuclear technician Mordechai Vanunu’s disclosures, for example, estimated that Israel had produced enough plutonium for 100 to 200 nuclear warheads (Sunday Times 1986a, 1986b, 1986c).3 In the public debate, this quickly became Israel possessing 100 to 200 nuclear warheads, the estimate that has been most commonly used ever since. Analysts are uncertain about the operational history or efficiency of the Dimona reactor’s operation over the years, but plutonium production is thought to have continued after 1986. The International Panel on Fissile Materials estimates that as of the beginning of 2020, Israel may have a stockpile of about 980 ± 130 kilograms of plutonium (International Panel on Fissile Materials 2021). That amount could potentially be used to build anywhere between 170 and 278 nuclear weapons, assuming a second-generation, single-stage, fission-implosion warhead design with a boosted pit containing 4 to 5 kilograms of plutonium.4

Total plutonium production is a misleading indicator of the actual size of the Israeli nuclear arsenal, however, because Israel—like other nuclear-armed states—most likely would not have converted all of its plutonium into warheads; a portion is likely stored as a strategic reserve. Additionally, the total number of deliverable warheads would presumably be tied to Israel’s limited number of aircraft and missiles that are equipped to deliver nuclear weapons, as well as to the limited number of targets that Israel would seek to strike in a conflict. As a result, estimates of the Israeli nuclear stockpile numbering in the hundreds of warheads may be exaggerated.

US government assessments offer more conservative estimates of Israel’s nuclear arsenal. A classified 1999 Defense Intelligence Agency report leaked in 2004 described Israel’s nuclear arsenal as numbering between 60 and 80 warheads in 1999, with the potential to grow to between 65 and 85 warheads by 2020 (Defense Intelligence Agency 1999).5 In a similar vein, in 1998 a RAND Corporation study commissioned by the Pentagon concluded that Israel had enough plutonium to build 70 nuclear weapons (Schmemann 1998).

During the two decades that have passed since the DIA report, Israel presumably has continued the production of plutonium at Dimona for some of that time. Given Israel’s presumed surplus of plutonium at this stage, the Dimona reactor’s current primary role is likely producing tritium, in order to replenish the material as it decays. The Dimona complex has probably also continued producing nuclear warheads. Many of those warheads were probably replacements for warheads produced earlier for existing delivery systems, such as the Jericho II missiles and aircraft. Warheads for a rumored Jericho III ballistic missile would probably replace existing Jericho II warheads on a one-for-one basis. Warheads for the rumored submarine-based cruise missile, if true, would be in addition to the existing arsenal but probably only involve a relatively small number of warheads.

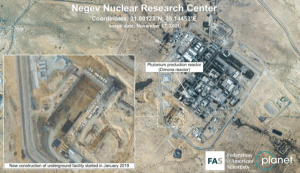

The reactor at Dimona is nearing the end of its useful design life, and the condition of the aluminum reactor pressure vessel––which cannot be replaced as part of a life-extension project––is believed to be deteriorating. Nevertheless, Israeli officials have indicated that they intend to keep the reactor operating until 2040 (Kelley and Dewey 2018). Satellite photos from February 2021 indicate that Dimona is currently undergoing its largest construction project in decades, with a large dig several stories deep located near the reactor (Gambrell 2021). It is unclear whether this new construction is related to Dimona’s life-extension campaign. Eventually, the Dimona reactor will need to be replaced; however, Israel’s non-party status to the Non-Proliferation Treaty means that it may face challenges purchasing a replacement reactor from another country. This is because it would theoretically be subject to strict export controls by the Nuclear Suppliers Group (Kelley and Dewey 2018).

Nuclear-capable aircraft

Since the 1980s, the F-16 has been the backbone of the Israeli Air Force. Over the years, Israel has purchased well over 200 F-16s of all types, as well as specially configured F-16Is. Various versions of the F-16 serve nuclear strike roles in the US Air Force and among NATO allies, and the F-16 is the most likely candidate for air delivery of Israeli nuclear weapons at the present time.

Since 1998, Israel has also used its 25 Boeing F-15E Strike Eagles for long-range strike and air-superiority roles. The Israeli version, known as the F-15I (or “Baz”), is characterized by greater takeoff weight—36,750 kilograms—and range—4,450 kilometers—than other F-15 models. Its maximum speed at high altitude is Mach 2.5. The plane has been further modified with specialized radar that has terrain-mapping capability and other navigation and guidance systems. In the US Air Force, the F-15E Strike Eagle has been given a nuclear role. It is not known if the Israeli Air Force has added nuclear capability to this highly versatile plane, but when Israel sent half a dozen F-15Is from Tel Nof air base to the United Kingdom in September 2019, a US official privately commented that Israel had sent its nuclear squadron (Kristensen 2019).

Israel has recently purchased 50 F-35s from the United States, becoming the first non-US country to operate the aircraft. The Israeli version of the aircraft––which will include indigenously designed electronic warfare suites, guided bombs, and air-to-air missiles––is known as the F-35I (named “Adir” for “awesome” or “mighty”). As of September 2021, Israel has received 30 F-35Is, operating them in three squadrons from Nevatim Air Base: the 140th (“Golden Eagle”) squadron, the Israeli Air Force’s first squadron of F-35s; the 116th (“Lions of the South”) squadron; and the 117th (“First Jet”) squadron, the latter of which is currently operating only as a training squadron. The remaining 20 F-25s are scheduled to be delivered by 2024 (Gross 2021; Pansky 2020). The F-35 squadrons are gradually replacing the aging F-16s; the 117th squadron was deactivated in October 2020 in order to swap out its F-16C/D aircraft with the requisite F-35 training systems (Gross 2020). The US Air Force is upgrading its F-35As to carry nuclear bombs, and Israel’s Channel 2 reported that an unnamed “senior level US official” refused to say if Israel had requested such an upgrade for its F-35s (Channel 12 2014).

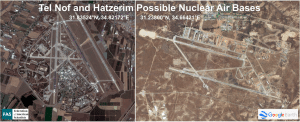

It is especially difficult to determine which Israeli wings and squadrons are assigned nuclear missions and which bases support them. The nuclear warheads themselves may be stored in underground facilities near one or two bases. Israeli F-16 squadrons are based at Ramat David Air Base in northern Israel; Tel Nof and Hatzor air bases in central Israel; and Hatzerim, Ramon, and Ovda air bases in southern Israel. Of the many F-16 squadrons, only a small fraction—perhaps one or two—would actually be nuclear-certified with specially trained crews, unique procedures, and modified aircraft. The F-15s are based at Tel Nof Air Base in central Israel, and Hatzerim Air Base in the Negev desert. We cautiously suggest that Tel Nof Air Base in central Israel and Hatzerim Air Base in the Negev desert might have nuclear missions.

Land-based ballistic missiles

Israel’s nuclear missile program dates back to the early 1960s. In April 1963, several months before the Dimona reactor began producing plutonium, Israel signed an agreement with the French company Dassault to produce a short-range surface-to-surface ballistic missile. The missile system became known as the Jericho (or MD-620), and the program was completed around 1970 with 24 to 30 missiles.

Most sources assert that Jericho was a mobile missile, transported and fired from a transportable erector launcher (CIA 1974). But there have occasionally been references to possible silos for the weapon. A US State Department study produced in support of National Security Study Memorandum 40 in May 1969 concluded that Israel believed it needed a nearly invulnerable nuclear force to deter a nuclear first strike from its enemies, “i.e., having a second-strike capability.” The study stated: “Israel is now building such a force—the hardened silos of the Jericho missiles” (US State Department 1969d, 7; emphasis added). It is not clear that the claim of “hardened silos” constituted the assessment of the US intelligence community or whether it referred to early construction of what is now thought to be mobile launcher bunkers at Sdot Micha, and only a few subsequent sources—all non-governmental—have mentioned Israeli missile silos.6 We have not found any public evidence of Jericho silos.

In collaboration with South Africa, in the late 1980s Israel developed the two-stage, solid-fuel, medium-range Jericho II that––for the first time––put the southern-most Soviet cities and the Black Sea Fleet within range. Jericho II, a modified version of the Shavit space launch rocket, was first deployed in the early-1990s, replacing the first Jericho. The Jericho was first flight-tested in May 1987 to approximately 850 kilometers (527 miles). The trajectory went far into the Mediterranean Sea. Another test in September 1989 reached 1,300 kilometers (806 miles). The US Air Force National Air Intelligence Center in 1996 reported the Jericho II range as 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) (NAIC 1996).

Given that approximately half of Iran (including Tehran) is beyond the range of Jericho II medium range ballistic missile, Israel is currently upgrading its arsenal with the newer and more capable three-stage Jericho III intermediate-range ballistic missile. The Jericho III reportedly has a range exceeding 4,000 kilometers, which would be able to target all of Iran, Pakistan, and all of Russia west of the Urals—including, for the first time, Moscow. Jericho III was first test-launched over the Mediterranean Sea in January 2008 and reportedly became operational in 2011. Unidentified defense sources told Jane’s Defence Weekly that Jericho III constitutes “a dramatic leap in Israel’s missile capabilities” (Jane’s Defence Weekly 2008, 5), but many details and its current status are unknown. In July 2013, Israel tested an “improved” version of the Jericho III missile––possibly designated the Jericho IIIA––with a new motor that some sources believe may offer the missile an intercontinental range exceeding 5,500 kilometers (Ben David 2013a; Ben David 2013b). It is unclear whether Israel is replacing its Jericho II missiles with Jericho IIIs on a one-for-one basis, or if they are being deployed concurrently, although the former is more likely. Upgrades of suspected launcher bunkers at Sdot Micha began in 2014.

In recent years, Israel has conducted several test-launches of what it calls “rocket propulsion systems.” These tests––which have been conducted in May 2015, May 2017, December 2019, and January 2020––are typically not accompanied by confirmation of an official test location (Agence France-Presse 2015; Ministry of Defense 2017; Kubovich 2019; Ministry of Defense 2020). However, local news sources and video footage indicate that the test site is likely to be Palmachim Air Base, Israel’s Jericho missile and Shavit space launch vehicle test site located on the Mediterranean coast (Trevithick 2019). In April 2021, video footage captured a significant blast at Sdot Micha Air Base, which external analysts have suggested was likely to be another rocket engine test (Lewis 2021). Unlike the previous tests, however, the Defense Ministry did not provide a statement confirming it as such. The flurry of rocket propulsion test activity has stirred up speculation that Israel could be developing a newer version of its Jericho missile, possibly known as Jericho-IV.

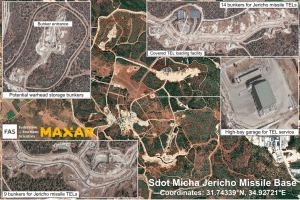

How many Jericho missiles Israel has is another uncertainty. Estimates vary from 25 to 100. Most sources estimate that Israel has 50 of these missiles and place them at the Sdot Micha facility near the town of Zakharia in the Judean Hills, approximately 27 kilometers east of Jerusalem. (There are many alternative spellings and names for the base, including Zekharyeh, Zekharaia, Sdot Micha, and Sdot HaElla.)

Commercial satellite images show what appear to be two clusters of what might be caves or bunkers for mobile Jericho launchers at Sdot Micha. The northern cluster includes 14 caves and the southern cluster has nine caves, for a total of 23 caves. Newly available high-resolution imagery indicates that each cave appears to have two entrances, which suggests that each cave can hold up to two launchers. The satellite images show that caves’ refurbishment began in 2014 and appeared complete in 2020. The upgrade also included upgrades to several tunnels to underground facilities. If all 23 caves are full, this would amount to 46 launchers. Each cluster also has what appears to be a covered high-bay drive-through facility, potentially for missile handling or warhead loading. A nearby complex with its own internal perimeter has four tunnels to underground facilities that could potentially be for warhead storage.

For the Jericho missiles to have military value, they would need to be able to disperse from their caves. The Sdot Micha base is relatively small at 16 square kilometers, and the suspected launcher caves are located along two roads, each of which is only about one kilometer long. This layout would provide protection against limited conventional attacks, but it would be vulnerable to a nuclear surprise attack. In a hypothetical crisis where the Israeli leadership decided to activate Israel’s nuclear capability, the launchers presumably would leave Sdot Mischa and take up positions in remote launch areas. A US State Department background paper from 1969 stated that there was “evidence strongly indicating that several sites providing operational launch capabilities are virtually complete” (US State Department 1969c, 4; emphasis added).

Sea-based missiles and submarines

Israel currently operates three German-built Dolphin-class and two Dolphin II-class diesel-electric submarines. The Dolphin II-class submarines are functionally identical to the Dolphin-class submarines, but with the addition of an Air Independent Propulsion system, which alleviates the need for the submarine to raise a snorkel to the surface to supply air to the engines and recharge the batteries (Sutton 2017). This reportedly allows the Dolphin II-class submarines to remain underwater for at least 18 days at a time––more than four times longer than the Dolphin-class submarines (Der Spiegel 2012). A sixth submarine––the final submarine in the fleet of Dolphin subs––is currently being fitted out (Shoval 2019). In 2017, the Netanyahu government signed a memorandum of understanding with Germany to acquire three additional Dolphin II-class submarines to replace the three older Dolphin submarines; however, the procurement deal has been delayed due to an ongoing corruption scandal (Opall-Rome 2017). Although Israel’s submarines are home-ported near Haifa on the Mediterranean coast, in recent years they have occasionally sailed through the Suez Canal, as a likely deterrence signal to Iran (Times of Israel 2020; Times of Israel 2021).

In addition to six standard 533 millimeter torpedo tubes, Israel’s submarines are reportedly equipped with four additional specially-designed 650 millimeter tubes (Sutton 2017). Analysts speculate that the unusual diameter of these tubes means that they could be used to carry a sea-launched variant of the indigenously designed “Popeye Turbo” air-to-surface missile,7 although rumors about a range over 1,000 kilometers were probably exaggerated. The German magazine Der Spiegel reported in 2012 that the German government had known for decades that Israel planned to equip the submarines with nuclear missiles. Former German officials said they always assumed Israel would use the submarines for nuclear weapons, although the officials appeared to repeat old rumors rather than provide new information. The article quoted another unnamed ministry official with knowledge of the matter: “From the beginning, the boats were primarily used for the purposes of nuclear capability” (Der Spiegel 2012).

Endnotes

- For the National Security Archive’s collections of declassified US government documents relating to Israel’s nuclear weapons capability, see Cohen and Burr 2006; Cohen and Burr 2015; Cohen and Burr 2016; and Cohen and Burr 2020.

- For examples of claims about tactical and advanced nuclear weapons, see Hersh 1991: 199–200, 216–217, 220, 268, 276 (note), 312, 319).

- Frank Barnaby, who cross-examined Vanunu on behalf of the Sunday Times, stated in 2004 that the estimate for Israel’s plutonium inventory—sufficient for “some 150 nuclear weapons”—was based on Vanunu’s description of the reprocessing plant at Dimona (Barnaby, 2004: 3–4).

- The four to five kilograms of plutonium per warhead assumes high-quality technical and engineering performance for production facilities and personnel. Lower performance would need a greater amount of plutonium per warhead and therefore reduce the total number of weapons that Israel could potentially have produced.

- The secret document was leaked and reproduced in Scarborough (2004: 194–223). It is important to caution that as a Defense Intelligence Agency document, the report does not necessarily represent the coordinated assessment of the US intelligence community as a whole, only the view of one part of it. An excerpt from the Defense Intelligence Agency report is available at Kristensen and Aftergood (2007).

- For an example of sources claiming Jericho missiles are deployed in silos, see Cordesman (2008). Cordesman references the Nuclear Threat Initiative country profile on Israeli missiles as the source for the silo claim. The NTI has since updated its page, which no longer mentions silos. See: https://www.nti.org/countries/israel/.

- For a lengthier exploration of the history of Israel’s sea-launched missile capability, see the 2014 Israel Nuclear Notebook, available at: Kristensen and Norris 2014.

Published at thebulletin.org

We remind our readers that publication of articles on our site does not mean that we agree with what is written. Our policy is to publish anything which we consider of interest, so as to assist our readers in forming their opinions. Sometimes we even publish articles with which we totally disagree, since we believe it is important for our readers to be informed on as wide a spectrum of views as possible.