She’s one of a number of young women leaders who offer a refreshing contrast to right-wing populism.

By John Nichols

8 March, 2018

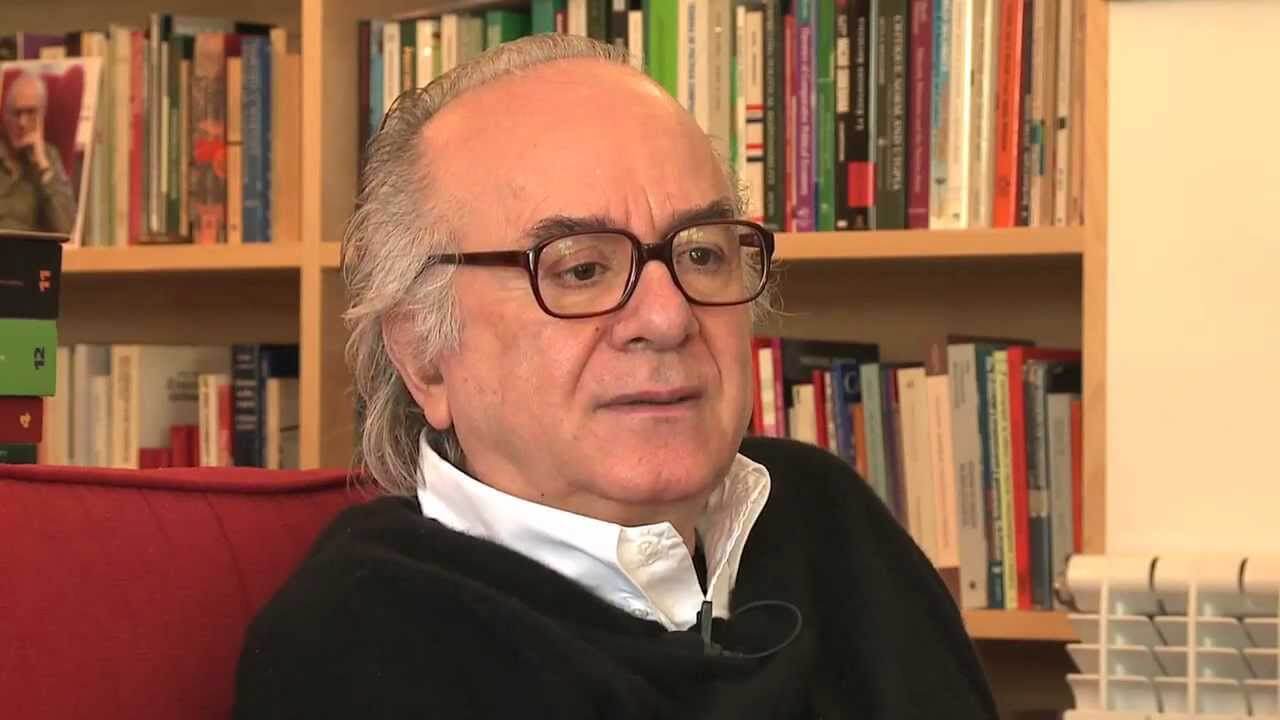

Another storm is sweeping into Reykjavík on this dark and cold late-winter evening, but in the downstairs hall of the century-old Hannesarholt cultural house, several dozen Icelanders are basking in the warmth of their country’s rich literary heritage. The lecturer tonight is a small woman with a large personality. Her enthusiastic two-hour presentation, punctuated with dramatic readings, wry humor, and songs, traces the evolution of the love story across the centuries. The emphasis is on the evolving role of women and the emergence of feminist sensibilities. The crowd is thrilled by the literary depth and intellectual breadth of the evening and rewards Katrín Jakobsdóttir with a standing ovation, which she graciously accepts before heading back to her day job—as prime minister of Iceland.

Energetic and impassioned, determined to lead not merely with legislation but with lessons, Jakobsdóttir is the first elected head of state who comes from a new breed of Nordic left-wing parties that link democratic socialism, environmentalism, feminism, and anti-militarism. She is, as well, one of a number of young left-leaning women who have emerged as prime ministers and party leaders in countries around the world at the same time that the United States has been coming to grips with the defeat of Hillary Clinton and the election of Donald Trump. While the United States wrestles with retrograde leadership—and the fantasy that a country can only be made great by doing something “again”—other countries are electing women who, in the words of Laura Liswood, secretary general of the Council of Women World Leaders, are “channeling today’s zeitgeist.”

“Women represent change, because they’re from a historically unrepresented group, and younger women represent a generational shift as well,” says Liswood, who for decades has studied the role of women in politics and government. “It’s almost as if everyone has permission to step away from the traditional ways of thinking. Society has changed sufficiently to talk about what is possible.” That embrace of possibility stands in stark contrast to the hidebound and reactionary messages sent by Trump’s election and his approach to governing. It also offers perspectives on how to forge a new politics that might give the United States permission to step away from its own traditional ways of thinking. There will always be those who embrace an American-exceptionalist dogma that insists there is nothing to learn from the rest of the world—and even less to learn from a remote island nation with a population that’s dwarfed even by small American states—but Iceland has captured a lot of imaginations. When I tweeted about the new prime minister’s left-wing politics and agenda after she assembled her coalition government last fall, I got 72,000 likes—and a lot of responses from Americans asking “How can I move there?” or, better yet, “Can we have one of these please?”

Settled into a chair in the modest conference room outside her office in the former Danish prison that serves as Iceland’s Stjornarrad (Cabinet House), Jakobsdóttir acknowledges the sudden interest in the country’s political progression. “I can understand,” says the literary critic who became prime minister. “It’s a little different.”

The international press has referred to Jakobsdóttir as “the anti-Trump.” And as she races to implement Iceland’s sweeping pay-equity law (quoting John Stuart Mill and talking about “the inequality that has the deepest roots in us all”); charges the head of Iceland’s largest conservation NGO with running the environment ministry; and discourses knowledgeably about the economic and social changes that will extend from automation, it’s easy to understand why.

But the “anti-Trump” label draws an eye-roll from Jakobsdóttir. She isn’t preoccupied by a desire to square off against the US president, either on Twitter or on the global stage. She’s much more interested in showing what Iceland can do, and in establishing a new model for what a leader might look and act like in the 21st century. When she appeared at the One Planet Summit in Paris last December—just months after Trump announced that he would withdraw the United States from the Paris climate agreement of 2015—Jakobsdóttir didn’t spend her time griping about US obstructionism; she came to announce her country’s plans for “going further” than the goals of the accord. Promising “a carbonless Iceland in 2040,” she cheekily proposed a race to ditch fossil fuels: “There are other nations making such goals, but our time schedule is ambitious, and we are going to be five years ahead of our neighbors in the Nordic countries.”

For Jakobsdóttir, politics is the art of the imaginable. Not of sweeping assertions and empty-headed certainty, mind you—she knows she’s the leader of a small country that has seen wild political mood swings since 2008, when it experienced the largest systemic banking collapse (relative to the size of its economy) of any nation in history. And she knows that the coalition government she now leads—which aligns her proudly socialist, environmentalist, feminist Left-Green Movement with a pair of center-right parties that are not particularly popular among her own party’s activist base—is an unprecedented project that is held together in no small part because of her status as the most trusted political figure in Iceland. She recognizes that politics in Iceland, and perhaps internationally, must produce smart, forward-looking alternatives to the toxic mix of right-wing populism, yearning for an unenlightened past, and lies about the future that has emerged in an age of desperate but often ill-focused anger over dead-end neoliberalism.

“We are trying to do things differently,” Jakobsdóttir says. In a world where most leaders of countries are still men, and where a good many of those men root their understandings in decades-old political models and practices, it’s worth noting that a 42-year-old feminist who embraces the #MeToo movement, recalls that “I began my political participation through demonstrations,” and gets excited about the way that grassroots movements can change politics and society is still a rarity on the global stage. “I’ve gone to one international meeting, which was the global summit in Paris,” Jakobsdóttir says. “And I noticed that there were a lot fewer women than men. So I was like, ‘OK, the numbers are not too high for us right now. We’ve got to change that.’”

Will we? “Oh, yes, I think that’s doable.”

Jakobsdóttir has a thing for the word “doable.” She uses it a lot—and with a refreshing confidence that not just her own small country but the world can and will be transformed, politically, socially, and culturally, for the better.

Mobilizing Iceland to address climate change and then leveraging that mobilization to influence the rest of the world? “It’s huge, but it’s doable,” Jakobsdóttir says. “I can already see that the other Nordic countries are saying [that they want to be] carbon-neutral by 2045—so it’s a little bit of a race. And you can’t do this just by reducing emissions. We also have to change the way we are using lands, restoring wetlands—really change the way we think. But, yes, we can do that.”

Jakobsdóttir is, in fact, doing just that: not merely capitalizing on Iceland’s wealth of renewable resources, which she admits provide “a head start,” but also organizing unexpected groups to be part of this new thinking—such as the Icelandic sheep farmers who propose to offset carbon emissions by investing in topsoil and wetlands reclamation, planting trees, and switching to renewable fuels. “The sheep farmers are ready, really, to cooperate with the government on how we can make sheep farming carbon-neutral in Iceland in a few years,” Jakobsdóttir says. “You never know if you’re going to achieve a goal or not, but I’m really excited about this, because I think it’s doable.”

What else is doable? “Closing the [gender] pay gap is doable,” she replies. “We have said that we are going to implement the equal-pay standard in five years.”

Putting Iceland’s money to work “for the people in this country”? Yes, that’s also “doable.” When talk turns to economic issues, the prime minister cites Thomas Piketty, the French economist and author of the 2013 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, and holds forth on the connections between austerity policies and inequality. Jakobsdóttir’s party campaigned on a promise not just to hike taxes on large companies and the rich but to make the country’s financial system more responsive to human needs. The Left-Green Movement wants to establish Iceland—which had a prime minister step down in 2016 after his family’s secret offshore holdings were revealed in the Panama Papers—as one of the “pioneering countries in which currency speculation and short-term profiting off of capital flows is taxed, thus discouraging speculative capital transfers.” Doable? “Yes, well, we of course are in this unique position [where the government owns] two out of three banks,” explains the leader of a country that responded very differently to the global financial and economic meltdown of 2007–08 than did the United States—by jailing bankers and taking a stake in major financial institutions.

“That certainly helps,” I admit. “That certainly helps,” Jakobsdóttir repeats, with robust laughter, but then she adds that Iceland, by taking advantage of its renewed economic vitality, can get to work “restoring or rebuilding this public infrastructure.” That’s a big deal, because, after too many punitive cuts during the turmoil that followed the banking crisis, the government she leads is “really founded on the mission to rebuild the public structure in Iceland.”

Jakobsdóttir argues that a lot of things are “doable” if political leaders decide to break long-established patterns. In many countries, people have been beaten down by neoliberal austerity policies that have blurred the lines between the traditional parties. There’s a search, Jakobsdóttir insists, for a politics that addresses human needs rather than always bending to the demands of bankers and distant investors. Even the more conservative parties in her unlikely coalition government recognize this, she insists, which is why they’ll be able to keep working together.

Jakobsdóttir sounds a little like Bernie Sanders when she starts talking about pulling together people of varying political views and ideologies to achieve fundamental goals. And that’s no coincidence: When I mention that Sanders has been talking about the changes in Iceland (“We must follow the example of our brothers and sisters in Iceland and demand equal pay for equal work now, regardless of gender, ethnicity, sexuality or nationality,” the Vermont senator wrote on Facebook in January), the prime minister lights up. “I’m a fan of him. Yes, yes, of course I’m a fan,” she says. “I really liked his message when he was campaigning, trying to become the presidential candidate for the Democrats. He was talking, really, about Nordic welfare. It was not what we would call ‘radical left’ in Iceland; it was traditional Nordic left-wing welfare that he was talking about, with the emphasis on equality—which I have been talking about for years. For years.”