The Militant, 19 March 1932

Lenin on the Paris Commune

(April 1911)

From The Militant, Vol. V No. 12 (Whole No. 108), 19 March 1932, p. 1.

Originally published in Rabochaya Gazeta, No. 4–5, April 28 (15), 1911.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

|

We reprint below an article by Lenin on the significance of the Paris Commune to the international working class. Lenin and the Bolsheviks absorbed the lessons taught by Marx and Engels on the Commune and found these invaluable in their struggle for the Russian Revolution. On the sixty-first anniversary of the Paris Commune it is befitting for us to reprint this brief writing penned by one who helped carry out the tasks the heroic Parisian Communards set themselves, continued their work, and began the class revenge of the world proletariat against the bloody suppression of the Commune by leading the Russian workers to the victorious Red October. – Ed. |

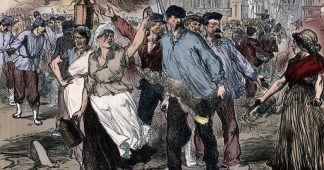

Forty years have passed since the proclamation of the Paris Commune. According to their custom, the French proletariat are honouring the memory of the revolutionary workers of March 18, 1871, by meetings and demonstrations. At the end of May they will again bring wreaths to the tombs of the Communards who were shot, the victims of the fearful “May Week”, and over their graves they will once more take the oath to fight untiringly until their ideas have conquered, until their cause has been completely victorious.

Why do the proletariat, not only in France but throughout the entire world, honour the workers of the Paris Commune as their forerunners? What was the heritage of the Commune?

The Commune broke out spontaneously. No one consciously prepared it in an organized way. The unsuccessful war with Germany, privations during the siege, unemployment among the proletariat and ruin among the petty-bourgeoisie; the indignation of the masses against the upper classes and against the authorities who had displayed their complete incapacity, an indefinable fermentation among the working class, which was discontented with its lot and was striving towards a different social system; the reactionary make-up of the National Assembly, which roused fears as to the fate of the republic—all this and many other things combined to drive the population of Paris to revolution on March 18, which unexpectedly placed power in the hands of the National Guard, in the hands of the working class and the petty-bourgeoisie which had joined in with it.

This was an event unprecedented in history. Up to that time power had customarily been in the hands of landlords and capitalists, i.e., in the hands of their trusted agents who made up the so-called Government. After the revolution of March 18, when the Thiers Government fled from Paris with its troops, its police and its officials, the people remained masters of the situation and power passed into the hands of the proletariat. But in modern society, enslaved economically by capital, the proletariat cannot dominate politically unless it breaks the chains which fetter it to capital. This is why the movement of the Commune inevitably had to take on a Socialist colouring, i.e., to begin striving for the overthrow of the power of the bourgeoisie, the power of capital, to destroy the very foundations of the present social order.

At first this movement was extremely indefinite and confused. It was joined by patriots who hoped that the Commune would renew the war with the Germans and bring it to a successful conclusions. It was supported by the small shopkeepers who were threatened with ruin unless there was a postponement of payments on debts and rent (the Government did not want to give them such a postponement but the Commune gave it). Finally, it had, at first, the sympathy of the bourgeois republicans, who feared that the reactionary National Assembly (the “backwoodsmen”, ignorant landlords) would restore the monarchy. But the chief role in this movement was of course played by the workers (especially the artisans of Paris), among whom Socialist propaganda had been energetically carried on during the last years of the Second Empire and many of whom even belonged to the First International.

Only the workers remained loyal to the Commune to the end. The bourgeois republicans and the petty-bourgeoisie soon broke away from it, the former afraid of the revolutionary Socialist proletarian character of the movement, and the others dropping out when they saw that it was doomed to inevitable defeat. Only the French proletariat supported their Government fearlessly and untiringly, they alone fought and died for it, for the cause of the emancipation of the working class, for a better future for all toilers.

Deserted by their allies of yesterday and supported by no one, the Commune was doomed to inevitable defeat. The entire bourgeoisie of France, all the landlords, the stockbrokers, the factory owners, all the great and small robbers, all the exploiters, combined against it. This bourgeois coalition, supported by Bismarck (who released a hundred thousand French soldiers who had been taken prisoner to put down revolutionary Paris), succeeded in rousing the backward peasants and the petty bourgeoisie of the provinces against the proletariat of Paris, and in surrounding half of Paris with a ring of steel (the other half was held by the German army). In some of the larger cities in France (Marseilles, Lyons, St. Etienne, Dijon, etc.) the workers also attempted to seize power, to proclaim the Commune, and come to the help of Paris, but these attempts soon failed. Paris, which had first raised the flag of proletarian revolt, was left to its own resources and doomed to certain destruction.

For the victory of the social revolution, at least two conditions are necessary: a high development of productive forces and the preparedness of the proletariat. But in 1871 neither of these conditions was present. French capitalism was still only slightly developed, and France was at that time mainly a country of petty-bourgeoisie (artisans, peasants, shopkeepers, etc.). On the other hand there was no workers’ party, the working class, which in the mass was unprepared and untrained, did not even clearly visualize its tasks and the methods of fulfilling them. There were no serious political organizations of the proletariat, no strong trade unions and co-operative societies.

But the chief thing which the Commune lacked was the time to think out and undertake the fulfillment of its programme. It hardly had time to start working, when the Versailles government, supported by the entire bourgeoisie, opened military operations against Paris. The Commune had to think first of all of defence. Right up to the very end, May 21–28, it had no time to think seriously of anything else.

In spite of such unfavorable conditions, in spite of the brevity of its existence, the Commune found time to carry out some measures which sufficiently characterize its real significance and aims. The Commune replaced the standing army, that blind weapon in the hands of the ruling classes, by the armed people. It proclaimed the separation of church from State, abolished the State support of religious bodies (i.e., State salaries for priests), gave popular education a purely secular character, and in this way struck a severe blow at the gendarmes in priestly robes. In the purely social sphere the Commune could do very little, but this little nevertheless clearly shows its character as a popular, workers’ Government. Night work in bakeries was forbidden, the system of fines, this system of legalized robbery of the workers, was abolished. Finally, the famous decree was issued according to which all factories, works and workshops which had been abandoned or stopped by their owners, were to be handed over to associations of workers in order to resume production. And, as if to emphasize its character as a truly democratic proletarian Government, the Commune decreed that the salaries of all ranks in the administration and the government should not exceed the normal wages of a worker, and in no case should exceed 6,000 francs per year.

All these measures showed with sufficient clearness that the Commune was a deadly menace to the old world, founded on slavery and exploitation. Therefore bourgeois society could not sleep peacefully so long as the Red Flag of the proletariat waved over the Paris City Hall. When at last the organized force of the Government had managed to defeat the poorly organized forces of the revolution, the Bonapartist generals who bad been beaten by the Germans and who were brave only when fighting their defeated countrymen, these French Rennenkampfs and Meller-Sakomelskys, organized such a slaughter as Paris had never known. About 30,000 Parisians were killed by the ferocious soldiery, about 45,000 were arrested and many of these were afterwards executed, thousands were imprisoned or exiled. In all, Paris lost about 100,000 of its sons, including the best workers of all trades.

The bourgeoisie were satisfied. “Now we have finished with Socialism for a long time,” said their leader, the bloodthirsty dwarf, Thiers, after the bloodbath which he and his generals had arranged for the proletariat of Paris. But these bourgeois crows cawed in vain. Six years after the suppression of the Commune, when many of its fighters were still pining in prison or in exile, a new workers’ movement rose in France. A new Socialist generation, enriched by the experience of heir predecessors and no whit discouraged by their defeat, picked up the flag which had dropped from the hands of the fighters of the Commune and bore it boldly and confidently forward, with cries of: “Long live the social revolution! Long live the Commune!” And a few years after that, the new workers’ party and the agitation raised by it throughout the country, compelled the ruling classes to release the imprisoned Communards, who were still in the hands of the government.

The memory of the fighters of the Commune is not only honoured by the workers of France but by the proletariat of the whole world, for the Commune did not fight for any local or narrow national aim, but for the freedom of toiling humanity, of all the downtrodden and oppressed. As the foremost fighter for the social revolution, the Commune has won sympathy wherever there is a proletariat struggling and suffering. The picture of its life and death, the sight of a workers’ government which seized the capital of the world and kept it in its hands for over two months, the spectacle of the heroic struggle of the proletariat and its sufferings after defeat—all this has raised the spirit of millions of workers, aroused their hopes and attracted their sympathies to the side of socialism. The thunder of the cannon in Paris awakened the most backward strata of the proletariat from deep slumber, and everywhere gave impetus to the growth of revolutionary Socialist propaganda. This is why the cause of the Commune did not die. It lives to the present day in every one of us.

The cause of the Commune is the social revolution, the cause of the complete political and economic emancipation of the toilers. It is the cause of the proletariat of the whole world. And in this sense it is immortal.

Published at www.marxists.org